Archaeologists working in south-west Poland have made a remarkable discovery: a funerary ornament crafted from beetle parts, buried with a child over 2,500 years ago. The find, unearthed at the Hallstatt-period Lusatian Urnfield cemetery in Domasław, sheds new light on the symbolic and ornamental practices of prehistoric European communities.

A Unique Discovery in Grave 543

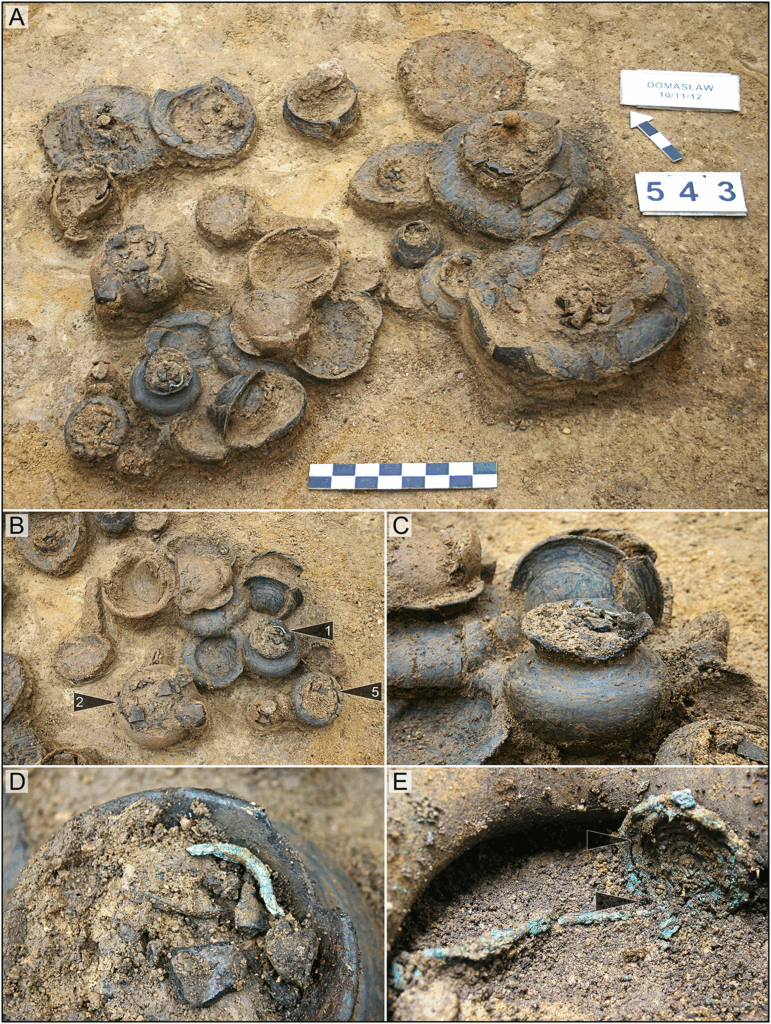

The cemetery at Domasław, excavated between 2005 and 2007, contains more than 800 cremation graves dating from around 850–400 BC, during the Hallstatt period. Among these, grave number 543 stands out as one of the most impressive. Inside its chamber, researchers uncovered several urns, each holding the remains of an individual.

Urn 1 contained the cremated bones of a child, aged about 9 to 10 years. Alongside the remains were fragments of goat or sheep bones, a harp-shaped bronze fibula, birch bark pieces, and traces of dandelion pollen. Most extraordinary, however, were the 17 fragments of insect exoskeletons carefully deposited in the urn.

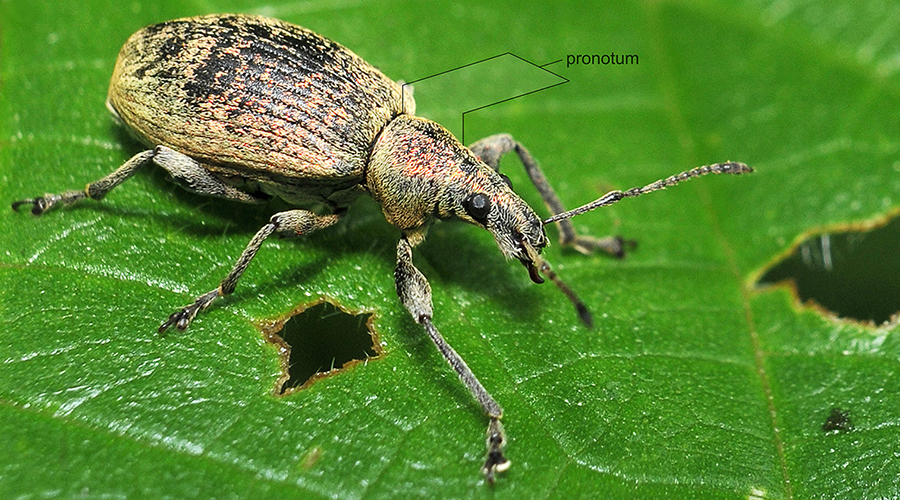

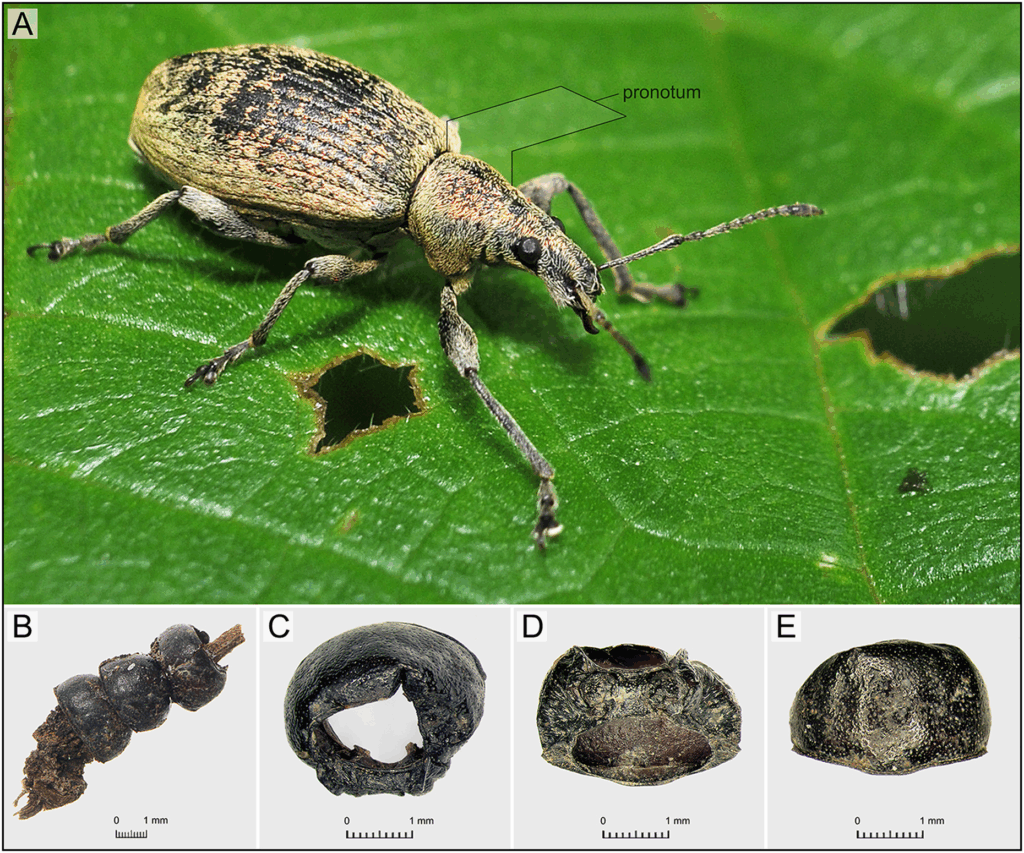

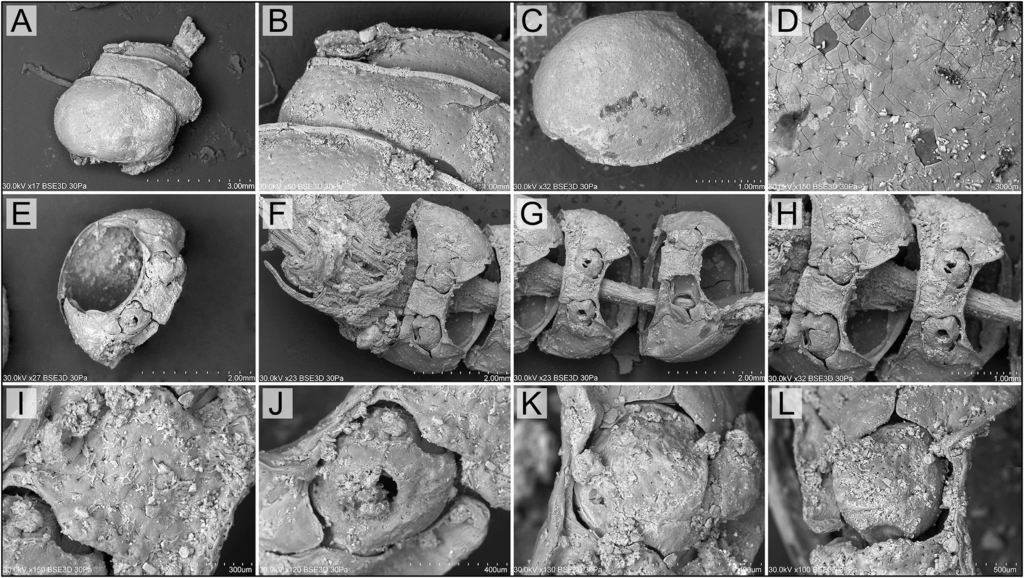

Detailed analysis revealed these belonged to Phyllobius viridicollis, a green weevil beetle still found in Europe today. Twelve whole pronota (the beetle’s shield-like thoracic plate) and five fragmentary pieces were preserved. Remarkably, several of these had been strung on a blade of grass, resembling a necklace or decorative ornament.

Intentional and Symbolic Placement

What makes this discovery so significant is the apparent intentional preparation of the beetle parts. The heads, legs, and abdomens had been removed in a uniform fashion, suggesting that the beetles were deliberately modified for ornamental use. The fact that some were strung together reinforces the interpretation that they were crafted into jewelry, possibly created specifically for the burial ritual.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Dr. Agata Hałuszko, who led the research, explained how such delicate organic remains survived for more than two millennia. The corrosion of the bronze fibula released copper compounds, which impregnated and preserved nearby organic materials—including the fragile beetle shells. This natural process, combined with meticulous excavation and electron microscopy analysis, allowed archaeologists to study the artifact in rare detail.

A Window Into Seasonal Rites

The presence of Phyllobius viridicollis also offers a unique clue to the timing of the burial. These beetles typically appear in May and live until July, while dandelions bloom from April through August. Taken together, the ecofacts suggest that the child’s burial likely took place in late spring or early summer, providing rare insight into the seasonal aspects of prehistoric funerary practices.

Cross-Cultural Parallels

The symbolic use of beetles in ornaments is not without precedent. Ethnographic accounts of the Hutsuls, a Slavic ethnic group from western Ukraine and northern Romania, describe necklaces made from rose and copper chafers, worn by girls as protective talismans. In the Victorian era, beetle wing cases were also fashionable in jewelry and textiles, celebrated for their iridescent shine.

Although it is impossible to know exactly what meaning the beetle ornament held for the community of Domasław, these parallels suggest that insects were valued both for their beauty and for their symbolic or magical associations. As insects often symbolize transformation and the fleeting nature of life, their use in a child’s burial may have carried profound spiritual significance.

Rare Evidence of Fragile Traditions

Because beetle exoskeletons are so delicate, ornaments made from them rarely survive in the archaeological record. Most would have decayed within months or years of burial. This makes the Domasław discovery particularly exceptional, offering direct evidence of ephemeral practices that would otherwise be invisible to history.

“Insects discovered in funeral contexts are most often associated with magical practices and the symbolism of life and death,” the research team notes. “The beetle pronota from grave 543 highlight the deliberate utilization of faunal materials in symbolic or ornamental capacities—evidence that is exceedingly rare in archaeology.”

Expanding Our Understanding of Prehistoric Europe

The discovery of the beetle ornament not only enriches our understanding of the Hallstatt culture but also broadens the scope of archaeological interpretation. By combining traditional excavation with advanced microscopic techniques, researchers can recover and study even the most fragile organic materials, deepening our knowledge of ancient societies.

This find from Domasław serves as a reminder that prehistoric communities expressed meaning and identity through more than just durable artifacts like bronze and pottery. Even fleeting, delicate objects—such as necklaces of beetle shells—carried symbolic weight in rituals of life, death, and memory.

As more discoveries like this come to light, they paint a richer, more complex picture of the human past, where even the smallest creatures played a role in the ceremonies of ancient Europe.

Interestingly, insects have also appeared in remarkable archaeological finds far from Europe. Just a few months ago, archaeologists in South Korea unearthed a 1,400-year-old Silla crown adorned with jewel beetle wings—the first of its kind. If you’d like to read more about this extraordinary discovery, click here: “First of Its Kind: 1,400-year-old Silla Crown Adorned with Jewel Beetle Wings Unearthed in South Korea.”

Hałuszko, A., Kadej, M., & Józefowska, A. (2025). Beetle body parts as a funerary element in a cremation grave from the Hallstatt cemetery in Domasław, south-west Poland. Antiquity, 1–9. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.10182

Cover Image Credit: Hałuszko, A., Kadej, M., & Józefowska, A. (2025)