The Trojan War is one of the most famous legends of Greek mythology, yet its historicity remains a topic of intense debate among scholars. Recently, a remarkable new discovery has emerged from the archives of Hittite texts, shaking the very foundations of how we perceive this legendary conflict. Published under the auspices of Oxford’s Michele Bianconi, the newly deciphered tablet—Keilfischurkunden aus Boghazköi 24.1—offers what could be one of the most tantalizing written connections between Bronze Age Anatolia and the epic tradition that culminated in Homer’s “Iliad.”

For many years, scholars questioned the existence of the city of Troy itself until Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations in 1873 confirmed its reality. However, the question of whether the war actually took place is still up for discussion. Some scholars argue that certain Hittite documents provide evidence supporting the occurrence of the Trojan War. But what do these documents reveal, and how do they connect to the epic tales we know?

What Was the Trojan War?

According to ancient Greek records, the Trojan War was a conflict between the Greeks and the city of Troy, located in the northwestern corner of Anatolia. The Greek forces were led by Agamemnon, the king of Argos, while the Trojans were ruled by the elderly Priam. This war was said to be a massive event, involving over a thousand ships launched from Greece. The Trojans were not alone; they had numerous allies from across western Anatolia, including the Lydians and Phrygians.

The war allegedly lasted a decade, during which the Greeks raided various cities along the Anatolian coast. Given the scale of this conflict, one would expect some independent corroboration of the event.

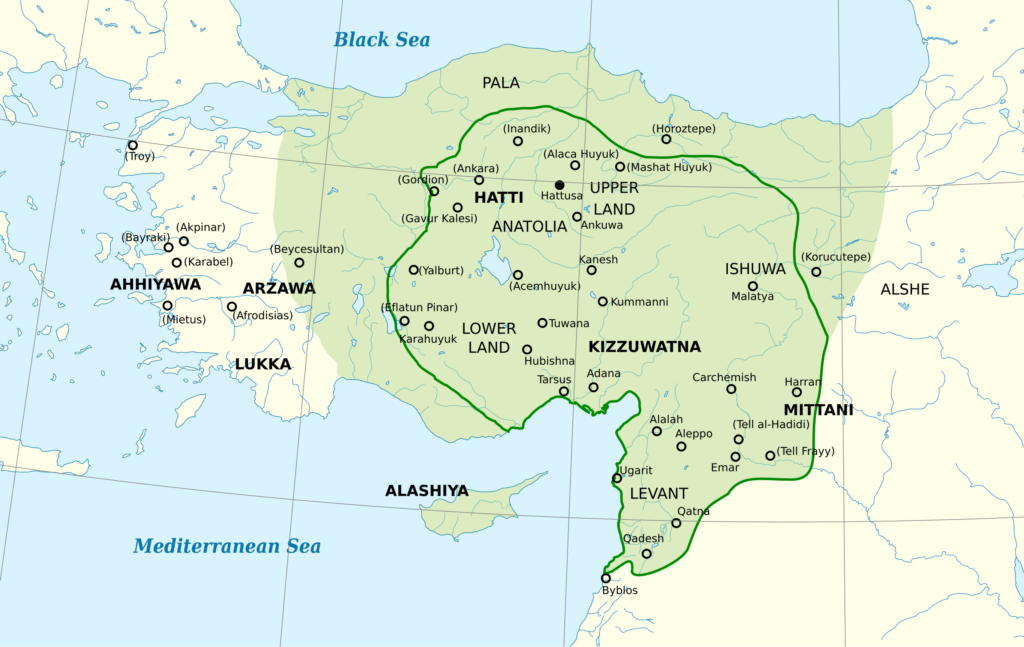

The Hittite Empire and Its Documents

The Hittite Empire, which dominated much of Anatolia around the traditional date of the Trojan War (circa 1200 BCE), has been a focal point for scholars seeking evidence of the war. Among the most significant findings from Hittite texts is the mention of a nation called ‘Ahhiyawa.’ Linguists generally agree that this name is connected to the ‘Achaeans,’ the term used by Homer in the “Iliad” to refer to the Greeks. These documents suggest that the Ahhiyawa were a powerful nation to the west of the Hittite Empire, likely corresponding to Mycenaean Greece.

One of the most notable documents is the Tawagalawa letter, dating to about 1250 BCE. This letter refers to a conflict involving ‘Wilusa,’ which most linguists agree is the Hittite form of ‘Ilios,’ another name for Troy. The letter states:

“The king of Hatti has persuaded me about the matter of the land of Wilusa concerning which he and I were hostile to one another, and we have made peace.”

This passage has often been interpreted as evidence of a conflict between the Hittites and the Greeks over Troy, leading many scholars to view it as confirmation of the Trojan War legend. However, the letter does not use the Hittite word for ‘war’; instead, it refers to general hostilities.

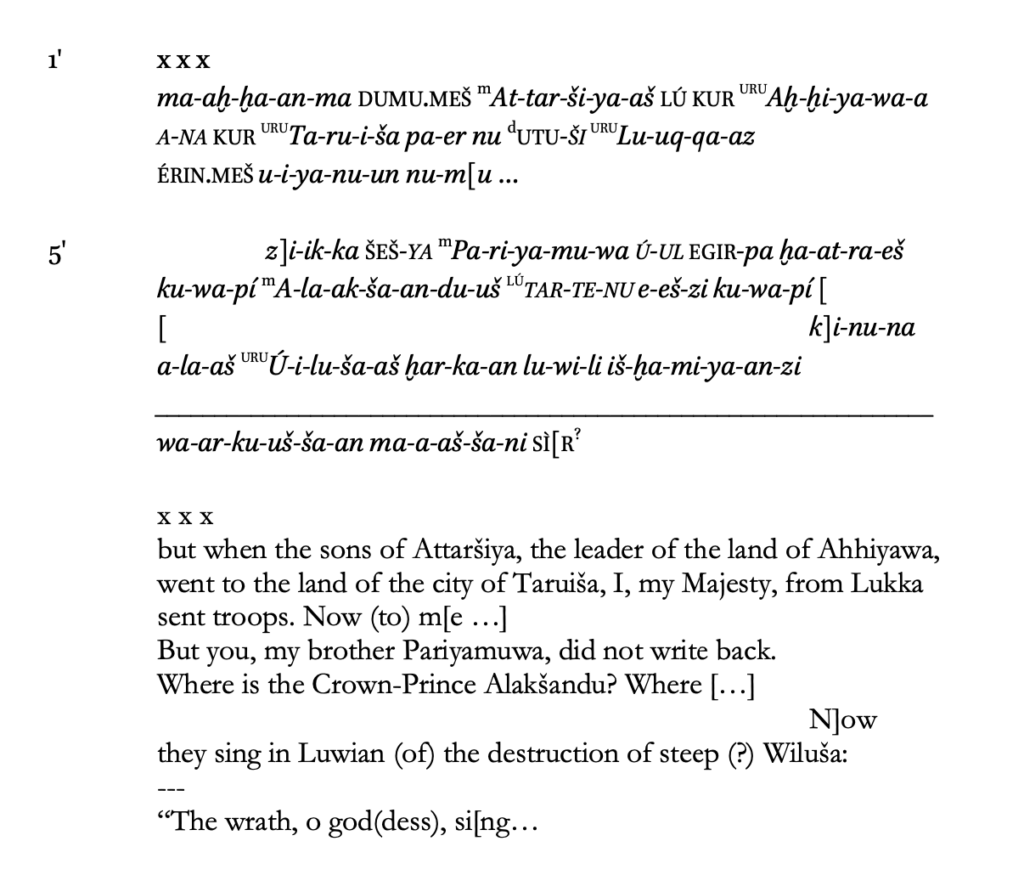

New Discoveries: Bridging Hittite History and Homeric Epic

The recent discovery of the Keilfischurkunden aus Boghazköi 24.1 tablet adds a new layer to our understanding of the Trojan War narrative. This tablet not only reinforces the geopolitical dynamics of the Late Bronze Age but also provides an unprecedented literary fragment that suggests a native Luwian poetic tradition dealing with the fall of Troy existed centuries before Homer.

The tablet recounts a royal correspondence between a Hittite monarch and Pariyamuwa, likely a regional king or vassal from Taruiša (Troy). It references a known figure from Hittite records—Attaršiya of Ahhiyawa—and his sons attacking Taruiša. This narrative aligns with earlier accounts where Attarşiya is depicted as a formidable Achaean leader in western Anatolia.

What’s particularly striking is the inclusion of a Luwian poetic fragment towards the end of the tablet, which appears to describe the fall of Wiluša (Troy). This rhythmical line bears a remarkable resemblance to the famous opening of Homer’s “Iliad”: “Sing, goddess, the wrath of Achilles…”

This tablet presents a groundbreaking glimpse into a poetic collection in the Luwian language, seemingly documenting the fall of Troy for the first time. Although the text is fragmentary, it reveals a rhythm that suggests it was designed for oral recitation. Its dactylic or spondaic patterns, intriguingly reminiscent of Homer’s hexameter, may indicate a more extensive epic tradition that existed in Anatolian courts, potentially predating the Iliad’s composition in the 8th century BCE.

Moreover, the Luwian poetic line that alludes to divine wrath and destruction hints at thematic and structural similarities with the Greek epic tradition. Considering that Troy was situated in Anatolia and that the region was home to a diverse, bilingual (or even multilingual) population—including Hittites, Luwians, and various Indo-European groups—the likelihood of a local narrative tradition surrounding the fall of Troy is both credible and now tentatively supported by this evidence.

The Interplay of Myth and History in the Trojan War Narrative

The exploration of the Trojan War, particularly through the lens of recent Hittite discoveries, invites us to reflect on the intricate relationship between myth and history. The newly deciphered tablet, Keilfischurkunden aus Boghazköi 24.1, not only enriches our understanding of the geopolitical landscape of the Late Bronze Age but also challenges us to reconsider the narratives that have shaped our perceptions of this legendary conflict.

As we delve into the Hittite texts, we find tantalizing hints of a poetic tradition that predates Homer, suggesting that the story of Troy was not merely a figment of Greek imagination but rather a tale rooted in the collective memory of the peoples of Anatolia. The references to Wiluša and the interactions between the Hittites and the Ahhiyawa provide a historical backdrop that could very well have inspired the epic tales we associate with the Trojan War.

However, it is essential to approach these findings with a critical eye. While the Tawagalawa letter and other Hittite documents offer intriguing insights, they do not provide definitive proof of the war as depicted by Homer. The peaceful resolution mentioned in the letter starkly contrasts with the violent destruction of Troy described in the “Iliad.” This discrepancy raises important questions about how legends evolve over time, often shaped by cultural narratives and the needs of the societies that tell them.

The Trojan War serves as a powerful reminder of how history and myth can intertwine, creating a rich tapestry of storytelling that reflects the values, fears, and aspirations of ancient civilizations. As we continue to unearth new evidence and reinterpret existing texts, we must remain open to the possibility that the truth of the Trojan War may be more complex than a simple tale of heroes and villains.

In the end, the story of Troy is not just about a war fought over a woman or a city; it is about the enduring human experience—our struggles, our triumphs, and our capacity for storytelling. The echoes of Ilion, captured in clay tablets and oral traditions, remind us that history is not a static record but a living narrative that continues to evolve. As we piece together the fragments of the past, we not only seek to understand the events that shaped our world but also to connect with the timeless themes that resonate through the ages.

Bianconi, M. (2024, April 1). Hittite tablet recounting the Trojan War? University of Oxford.

Cover Image Credit: Depiction of the Trojan Horse on a Corinthian aryballos (ca. 560 BC) found in Cerveteri (Italy). Wikipedia