Polish archaeologists have uncovered a remarkably well-preserved 4,000-year-old grave in Sudan’s Bayuda Desert, offering valuable new insights into burial customs, daily life, and environmental conditions during the Kerma period—one of the earliest and most powerful civilizations of ancient Nubia.

The discovery was made by a research team led by Henryk Paner of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of Warsaw. The team has been conducting systematic archaeological investigations in central Sudan for more than six years, an effort that marks a significant expansion of research in a region long considered one of the least explored parts of the country.

A Rare Burial from the Kerma Period

The grave dates to the Kerma period (circa 2500–1500 BCE), when the Kingdom of Kerma dominated large sections of the Nile Valley south of Egypt. Osteological analysis revealed that the buried individual was a man aged between 30 and 40, standing just over 164 centimeters tall. His skeleton indicates a strong, muscular build and clear signs of long-term physical strain.

According to researchers, these traits suggest a life of intense labor in a semi-desert environment, likely involving animal husbandry. Evidence from the site points to a limited but protein-rich diet and close contact with livestock—hallmarks of communities living on the margins of arable land.

The burial pit itself was shallow and irregularly oval, shaped by the rocky terrain of the desert. The body was placed on its back, with the head oriented east and slightly north. The legs were sharply bent and twisted to the right, with the feet resting on the pelvic bones. This distinctive posture is characteristic of older Kerma burials and reflects deeply rooted funerary traditions.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Grave Goods and Funeral Rituals

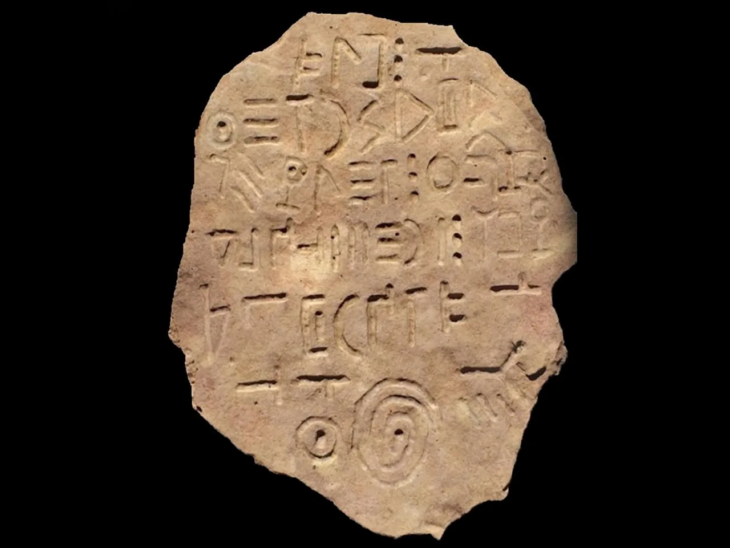

Behind the body, archaeologists uncovered two handmade ceramic vessels: a medium-sized jug with a spout positioned near ground level and an inverted bowl. Near the neck, they found 82 faience beads, likely part of a necklace worn at the time of burial.

Inside the jug, researchers identified charred plant remains, fragments of animal bones, coprolites, and beetle remains. Importantly, the vessel itself showed no signs of burning. This suggests that debris from a hearth—possibly used during a funeral feast—was deliberately placed inside the jug after the fire had burned out.

Scholars believe these remains represent ritual activity associated with burial ceremonies. Leftovers from communal meals may have been symbolically deposited in the grave, reinforcing social bonds between the living and the dead.

Pottery played a key symbolic role in Kerma funerary practices. Vessels were not merely containers for offerings but markers of identity. Archaeologists note that intentionally breaking, perforating, or inverting vessels rendered them “lifeless,” mirroring beliefs about death, transformation, and ancestor worship within Kerma society.

Reconstructing an Ancient Landscape

Environmental analysis of the cemetery hill adds another layer of insight. Although the area is now arid desert, sediment studies and botanical remains indicate that around 2000 BCE the landscape was significantly wetter. The region likely supported a savannah environment with grasses, low shrubs, and scattered trees—conditions more favorable for pastoral life.

As Paner notes, even modest archaeological sites can provide crucial data when studied through an interdisciplinary lens. The findings from this grave were published in Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa.

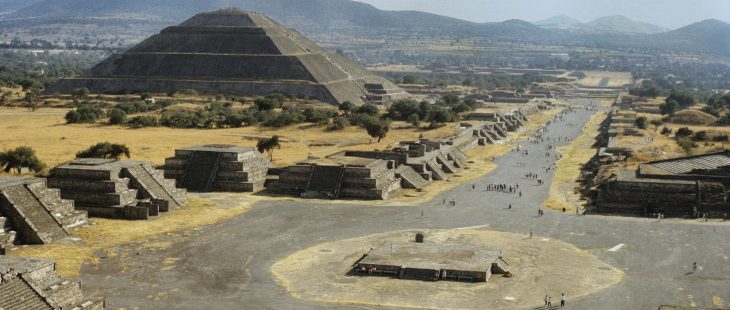

The Kerma Kingdom and Ancient Nubia

The Kingdom of Kerma represents one of Africa’s earliest urban societies and the first centralized state in ancient Nubia. Centered near the Third Cataract of the Nile, Kerma was known for its monumental mudbrick architecture, complex social hierarchy, and long-distance trade networks connecting sub-Saharan Africa with Egypt.

Far from being a peripheral culture, Kerma rivaled Egypt in wealth and military power during parts of the Middle Kingdom. Its people developed distinct artistic styles, religious practices, and burial traditions—many of which are still being uncovered through ongoing archaeological work.

A Window into Daily Life 4,000 Years Ago

This single grave from the Bayuda Desert brings together biological, cultural, and environmental evidence to illuminate everyday life in ancient Nubia. From physical labor and diet to ritual practice and climate, the discovery deepens our understanding of how Kerma communities adapted to challenging environments and expressed their beliefs about life and death.

As archaeological research in Sudan continues to expand, finds like this underscore the region’s critical role in the broader story of ancient African civilizations—and how much remains to be discovered beneath the desert sands.

Cover Image Credit: Sudan’s Bayuda Desert. Jozef Tóth / Wikipedia Commons