In a historic archaeological effort, researchers in Benin City have uncovered long-buried traces of royal architecture, artistry, and metalworking — offering the clearest glimpse yet into the origins of the legendary Benin Bronzes.

In a groundbreaking archaeological effort, researchers have unearthed new insights into the ancient Kingdom of Benin’s urban development, artistry, and cultural evolution. The Museum of West African Art (MOWAA) Archaeology Project, conducted between 2022 and 2024, marks the largest excavation in Benin City in half a century and one of the most extensive pre-construction archaeological programs ever undertaken in West Africa.

Rediscovering a Lost Royal Capital

Once the seat of the powerful Kingdom of Benin (c. AD 1200–1897), Benin City was famed for its sophisticated urban layout and artistic brilliance. Its most celebrated creations, the Benin Bronzes, stand as masterpieces of metalworking and historical storytelling. These intricate brass and bronze sculptures adorned the royal palace and depicted scenes of courtly life, warfare, and spiritual rituals.

However, the city suffered immense devastation in 1897 when British forces raided the royal palace, looting thousands of artworks and destroying much of its built heritage. For decades, the archaeological record remained largely unexplored — until the launch of the MOWAA project.

The MOWAA Archaeology Project: A Collaboration of Global and Local Expertise

Led by a consortium including MOWAA, the British Museum, the National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM), and research teams from the University of Cambridge and Wessex Archaeology, the MOWAA Archaeology Project combines international scholarship with local expertise. Over 60 Nigerian archaeologists and technicians participated, many gaining advanced field training through placements in London, Cambridge, and Cyprus — a major capacity-building legacy for West African heritage science.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

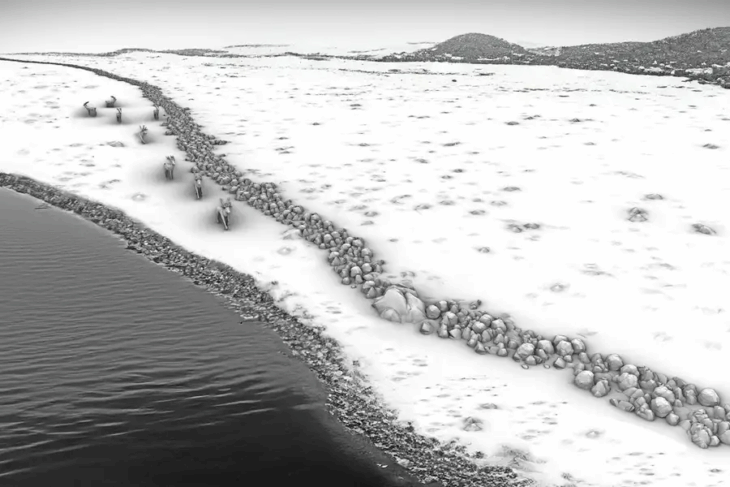

The excavations took place across two major construction sites: the MOWAA Institute and the Rainforest Gallery, both located within the historic core of Benin City. Using ground-penetrating radar (GPR), test-pit sampling, and large-scale open-area excavations, archaeologists documented deep cultural layers ranging from 1.5 to 3 meters, revealing a continuous sequence of human occupation that stretches from the first millennium AD to the modern post-independence era.

Tracing 1,000 Years of Urban and Artistic Evolution

Radiocarbon dating shows that some layers predate the rise of the Benin Kingdom itself, indicating that Benin City’s origins extend back more than a thousand years. These early layers suggest that the area was already an important settlement before the city’s royal and political institutions emerged.

The main occupation sequence begins around the fourteenth century, aligning with the consolidation of the Benin Kingdom. Layers from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries — Benin’s “high period” — correspond to the zenith of its political power, trade, and artistic production. Excavations revealed palatial architecture, ritual shrines, and zones of metalworking, offering unprecedented insight into the city’s social and spiritual life.

Among the most striking discoveries were ritual and artisanal features that reveal the spiritual and creative pulse of ancient Benin City.

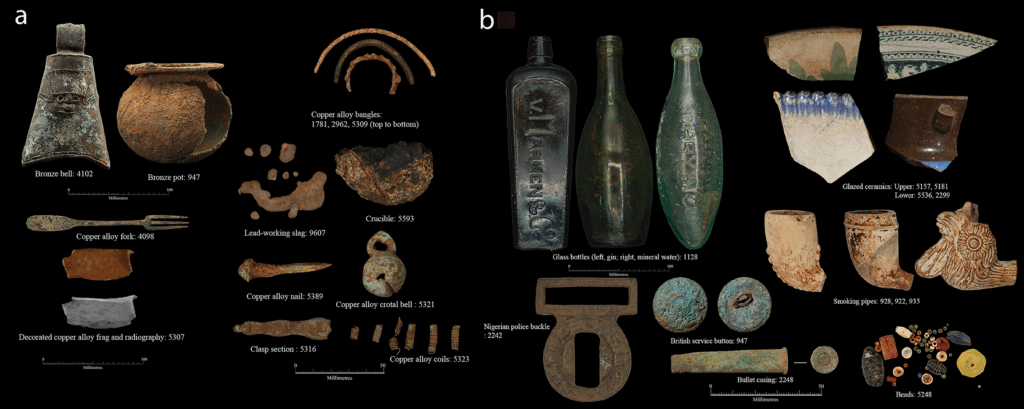

Archaeologists uncovered complex shrine areas marked by carefully arranged upturned pots, clusters of cowrie shells, and moulded chalk (nzu) — materials traditionally associated with purification and devotion. These ritual deposits likely belonged to sacred palace spaces, where spiritual ceremonies and royal offerings once took place.

Nearby, evidence of metalworking workshops emerged, including lead slag, crucible fragments, and traces of copper-alloy residues, offering rare physical proof of the sophisticated techniques used to create the world-renowned Benin Bronzes. Complementing these were finds of imported glass bottles and ceramics, such as nineteenth-century European gin and trade bottles, which point to Benin’s extensive trade connections and its role as a cosmopolitan hub linking West Africa to global commerce and cultural exchange.

From Royal Splendor to Colonial Transformation

Archaeological evidence also documents the aftermath of the 1897 British invasion, revealing layers of burning and debris associated with the palace’s destruction. Nearby, a newly mapped European Cemetery and remains of colonial buildings — possibly tied to early British administrative compounds — trace the area’s transition into the colonial era. Later deposits include artifacts from the colonial police headquarters and post-independence hospital, illustrating how the city’s heart continued to evolve and adapt across generations.

The Birthplace of the Benin Bronzes: Artisans and Innovation

The findings also offer valuable context for understanding the creation of the Benin Bronzes, which represent one of Africa’s greatest artistic achievements. Excavated evidence of metalworking furnaces, slag deposits, and copper-alloy fragments confirms that Benin City was a thriving center of metallurgical innovation, where generations of guild artisans mastered the lost-wax casting technique to produce intricate royal and ceremonial sculptures.

These new data link physical workshops with the living traditions of court artisans (Igun Eronmwon), connecting archaeological science with oral history and ethnography. The MOWAA project’s ongoing metallographic and elemental analyses aim to reconstruct how raw materials — including copper, tin, and lead — were sourced, processed, and transformed into art that defined an empire.

A New Era for West African Heritage Research

The MOWAA Institute, now under construction atop these historic layers, will serve as a world-class research, conservation, and storage center for archaeological materials from across West Africa. Its laboratories will analyze ceramics, metals, botanical remains, and organic residues to deepen understanding of past economies, diets, and environmental changes.

According to project co-director Dr. Sam Nixon of the British Museum, the excavations not only “redefine our understanding of Benin’s urban history” but also demonstrate how developer-led archaeology can coexist with modern infrastructure projects. By integrating heritage preservation with development, the project sets a precedent for sustainable cultural research across Africa.

Reconnecting the Past and Future of Benin City

The rediscovery of Benin City’s buried heritage resonates beyond archaeology. It supports Nigeria’s broader efforts to repatriate looted Benin Bronzes and reconnect them with their original cultural landscape. As the Museum of West African Art rises on this ancient ground, it promises to become both a repository of knowledge and a symbol of renewal — linking the city’s royal past with its creative future.

Through the MOWAA Archaeology Project, Benin City reclaims its place as a center of art, innovation, and resilience — a testament to Africa’s enduring legacy of urban sophistication and craftsmanship.

Folorunso, C., Nixon, S., Opadeji, S., Babalola, A., Le Quesne, C., Adamu, A., … Breeden, C. (2025). MOWAA Archaeology Project: enhancing understanding of Benin City’s historic urban development and heritage through pre-construction archaeology. Antiquity, 1–10. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.10189

Cover Image Credit: Folorunso et al., 2025, MOWAA Archaeology Project, Antiquity.