Deep within a remote limestone cave in southeastern Australia, archaeologists have uncovered a breathtaking link to the past — hundreds of delicate finger impressions, or finger flutings, preserved for up to 8,400 years. These ancient grooves, made by both adults and children, reveal rare insights into the ritual life of the GunaiKurnai people and are sparking worldwide interest in the archaeology of human gestures.

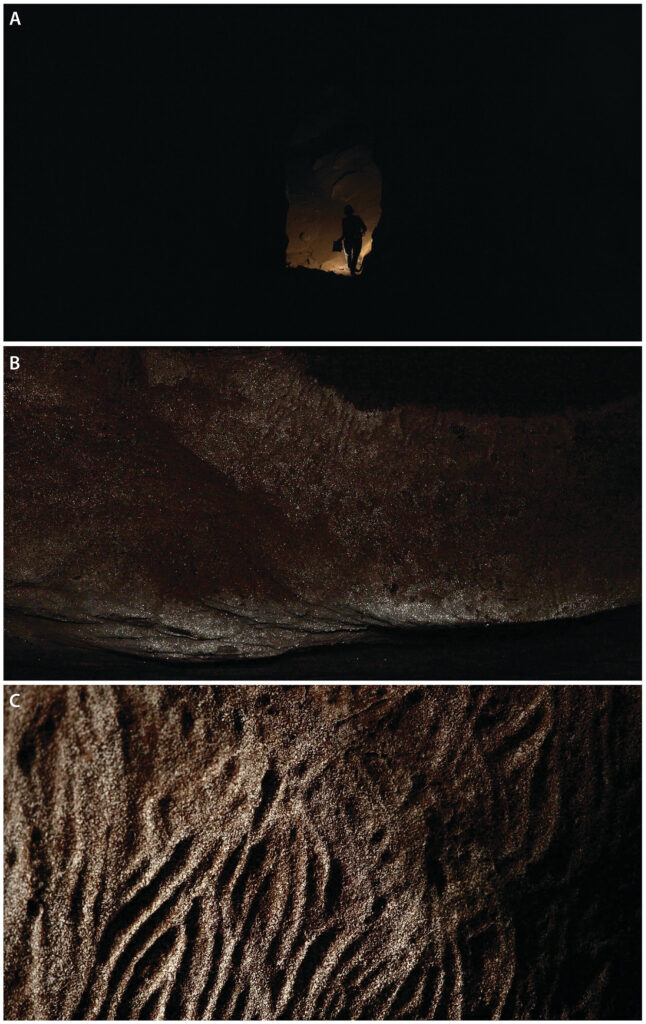

The discovery, documented in Australian Archaeology, took place at New Guinea II Cave in the lower Snowy River valley, Victoria — a sacred site in GunaiKurnai Country. The markings occur only on soft limestone surfaces glittering with microscopic calcite crystals, visible only under torchlight. Archaeologists believe this shimmering backdrop was no accident: the flutings were likely part of sacred practices carried out by mulla-mullung healers, whose spiritual traditions have been recorded in 19th-century ethnographies.

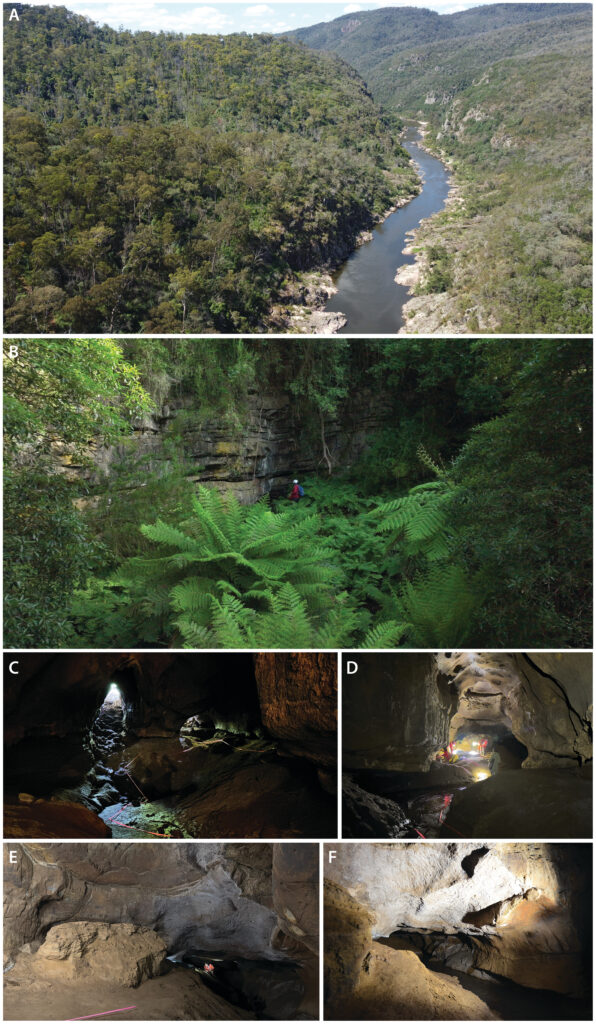

A Hidden World Beneath the Rainforest

The cave’s entrance lies tucked into a temperate rainforest valley. Beyond the reach of daylight, torch beams reveal walls that sparkle as though dusted with stars. It’s here that over 950 finger grooves have been recorded using high-definition 3D photogrammetry, allowing researchers to document every curve and overlap without touching the fragile surfaces

These flutings were created by dragging fingers across soft

“phantomised” limestone — a naturally decomposed rock surface kept moist by constant condensation. Over time, bacterial micro-ecosystems formed glittering calcite crystals that preserved the impressions. Unlike pigment rock art or stone carvings, finger flutings capture the very motion of ancient hands, offering a direct, physical trace of human contact with the cave walls.

Dating and Context

Radiocarbon dating of tiny charcoal fragments beneath decorated areas suggests that the flutings were made between roughly 8,400 and 1,800 years ago. The absence of hearths or domestic debris deep inside the cave suggests it was never a living space. Instead, its remote location, difficult access, and total darkness point to restricted ceremonial use — a place reserved for a select few within the GunaiKurnai community.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Ethnographic accounts collected by Alfred Howitt in the late 1800s describe mulla-mullung healers entering sparkling caves to extract crystals and mineral powders for spiritual purposes. Such materials were believed to confer healing powers or, in some cases, the ability to curse. Losing one’s crystals meant losing one’s power. The placement of the finger flutings exclusively on glittering surfaces echoes these beliefs.

Patterns of Touch

Photogrammetric analysis revealed complex sequences of overlapping marks, showing that the panels were used repeatedly over generations. In some areas, horizontal grooves were later crossed by vertical and diagonal lines. The orientation, depth, and grouping of the marks suggest coordinated actions, not random scraping.

Notably, some grooves are just 3–5 millimetres wide — the size of a child’s finger — and are positioned too high for a child to have reached unaided. This implies that children were lifted by adults to take part, suggesting intergenerational participation in the rituals.

Preserving an Intangible Heritage

The research team — led by the GunaiKurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation in collaboration with Monash University and international partners — emphasises that these markings are more than archaeological curiosities. They are a living cultural link for the GunaiKurnai people, embodying gestures that connect directly to ancestral tradition.

As archaeologist Bruno David notes, the flutings are “a bodily record of engagement with the sacred” — tangible evidence of spiritual interaction between humans and the natural world. To protect the site, all recording was done with non-invasive methods, and access remains tightly controlled.

The resulting 3D models are not only crucial for academic study but also serve as digital heritage for the GunaiKurnai community, allowing descendants to view and interpret the marks without risking damage to the cave.

A Global Perspective

While finger flutings are known from prehistoric caves in France and Spain — some dating back 40,000 years — they are rare in Australia. New Guinea II Cave now stands among the most significant examples in the Southern Hemisphere. Its combination of natural beauty, cultural meaning, and technological documentation sets a new benchmark for rock art research.

This discovery also broadens our understanding of prehistoric art forms. Unlike figurative paintings or carvings, flutings emphasise movement and touch. They preserve the physicality of human interaction — not a representation of life, but a trace of life itself.

Protecting a Fragile Legacy

The cave’s delicate microclimate has preserved the flutings for millennia, but even small disturbances could erase them. Modern drag marks, likely from untrained visitors decades ago, have already damaged some sections. The research underscores the need for strict preservation measures for rock art sites, particularly those that hold irreplaceable traces of intangible heritage.

For the GunaiKurnai people, these marks are more than archaeological data — they are a sacred inheritance. For the world, they offer a rare chance to witness an ancient, glittering handshake between humanity and the spirit of place.

Kelly, M., David, B., Rivero Vilá, O., Garate Maidagan, D., Delannoy, J. J., … Mullett, R. (2025). Finger flutings at New Guinea II Cave, lower Snowy River valley (Victoria), GunaiKurnai country. Australian Archaeology, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2025.2529627

Cover Image Credit: Australian Archaeology, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2025.2529627