Zvejnieki cemetery in Latvia, one of Europe’s largest Stone Age burial grounds, has revealed remarkable insights into equality, ritual, and identity among prehistoric hunter-gatherers, according to a new study published in PLOS ONE.

Archaeologists from an international team analyzed more than 150 stone tools buried with individuals at Zvejnieki, a site dating between 7500 and 2500 BC. Using a multi-proxy approach—combining geological, technological, functional, and spatial analysis—they uncovered evidence that men, women, and especially children were buried with stone tools in equal measure. This challenges long-standing assumptions that such tools were primarily associated with male hunters.

A Window Into Stone Age Lives

Zvejnieki, located near Lake Burtnieks in northern Latvia, contains over 330 graves and at least 350 individuals. Excavations began in the 1960s and continued into the 2000s, producing one of the richest archives of prehistoric burials in Europe. The recent “Stone Dead Project,” funded by UKRI and the European Research Council, revisited these collections to examine how stone tools were used in funerary contexts.

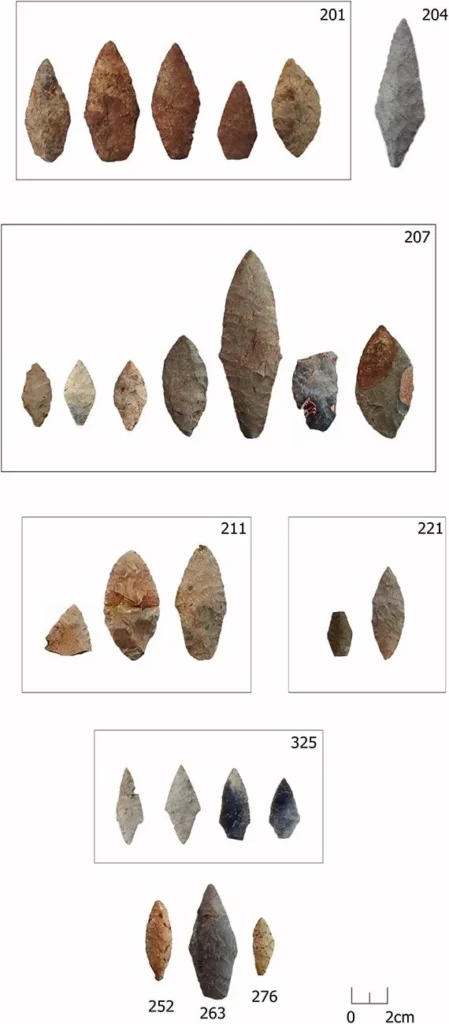

The researchers found that flaked flint artefacts—including flakes, blades, scrapers, knives, and bifacial points—were not only practical tools but also held symbolic value. While many showed no signs of wear, suggesting they were created specifically for burial, others bore microscopic traces of use, such as cutting bone, processing hides, or working with minerals.

“Stone tools were more than just hunting gear,” said lead author Dr. Anđa Petrović of the University of Belgrade. “They carried cultural and ritual significance, sometimes being deliberately broken or placed in meaningful ways during funerals.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Gender Equality in Death

Perhaps the most striking discovery is the absence of gender bias in grave goods. The study revealed that both men and women were equally likely to be buried with lithic tools. In fact, some of the richest tool assemblages were found in female and child burials.

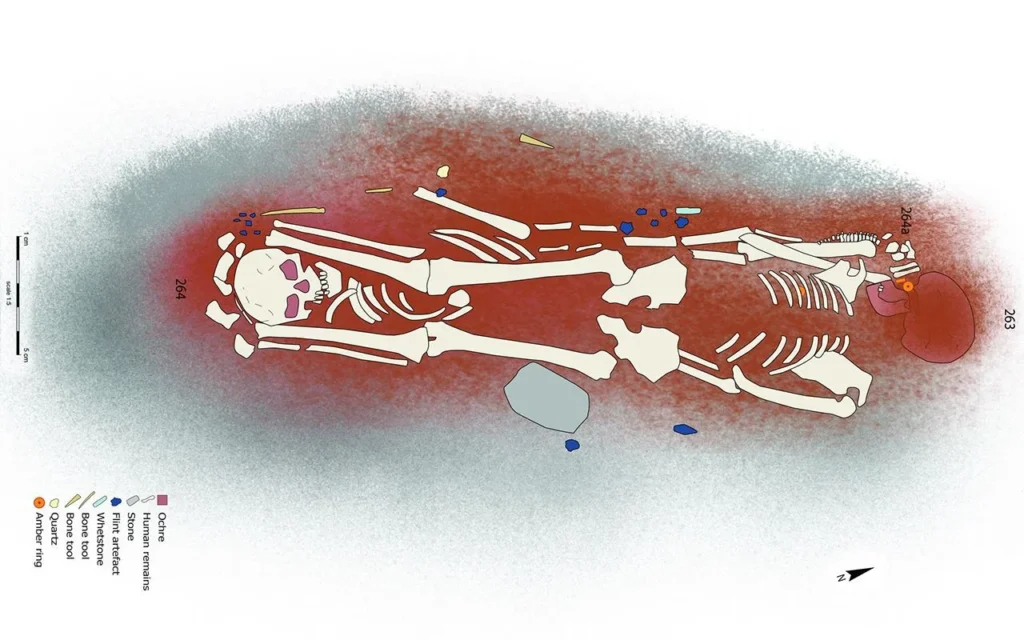

For instance, Burial 207, a young girl genetically identified as female, contained the largest number of bifacial points (often thought of as male-associated tools) ever found at Zvejnieki. Another female burial included traces of mineral-working tools, hinting at specialized roles or symbolic associations.

“This fundamentally changes how we view gender roles in Stone Age societies,” noted co-author Dr. Aimée Little from the University of York. “Grave goods show that identity and community values were expressed beyond simple male-hunter stereotypes.”

Children at the Center of Ritual

Another revelation is the prominence of children in funerary practices. Younger individuals, particularly children under 14, were more frequently buried with stone tools than adults. Some child burials even contained high concentrations of carefully made or unused tools, emphasizing their symbolic importance within the community.

Researchers suggest this may reflect beliefs about renewal, lineage, or the special role of children in ritual life. It also highlights the emotional and social dimensions of death in prehistoric communities, showing that children were far from marginal figures.

Ritual and Symbolism

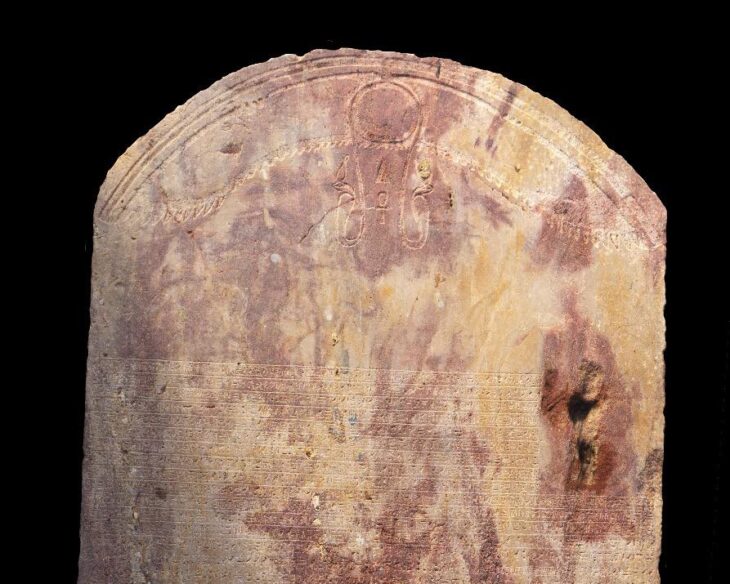

The analysis revealed intriguing patterns in how tools were placed. Scrapers were often positioned near the hands, while bifacial points clustered around torsos or belts, suggesting symbolic placement rather than practical use. Red ochre, amber ornaments, and clay “death masks” were also found in association with some graves, adding further ritual layers.

Importantly, the majority of tools date to the 4th millennium BC, when more elaborate funerary traditions flourished. Many were made of imported flint, indicating long-distance connections and exchange networks.

Broader Implications

The findings contribute to a growing body of research emphasizing diversity and complexity in Stone Age societies. They also highlight the importance of re-examining old collections with modern scientific methods, as many insights were hidden in archives for decades.

By showing that gender and age did not restrict access to valued objects, the Zvejnieki study challenges assumptions about hierarchy in prehistoric Europe. Instead, it points toward communities where tools, rituals, and identities were shared across social boundaries.

Beyond academic significance, the research resonates with modern conversations about equality, identity, and cultural heritage. It underscores how ancient societies navigated ideas of belonging and remembrance, offering a deep-time perspective on issues that continue to shape human experience.

As archaeologists continue to uncover more from Zvejnieki, the site remains a crucial key to understanding how Europe’s early hunter-gatherers viewed life, death, and what it meant to be human.

Petrović A, Bates J, Macāne A, Zagorska I, Edmonds M, Nordqvist K, et al. (2025) Multiproxy study reveals equality in the deposition of flaked lithic grave goods from the Baltic Stone Age cemetery Zvejnieki (Latvia). PLoS One 20(9): e0330623. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0330623