High in the heart of the Italian Alps, where jagged peaks rise above future Olympic venues, an extraordinary window into deep time has been uncovered. In the remote Valle di Fraele, between Livigno and Bormio, scientists have identified what is now considered the largest dinosaur tracksite in the Alpine region and one of the most extensive Late Triassic fossil footprint deposits ever found worldwide. Preserved on steep, almost vertical dolomitic rock faces, thousands of dinosaur footprints reveal a vibrant ecosystem that existed more than 200 million years ago, long before the Alps themselves were formed.

The site, which stretches for several kilometers inside Stelvio National Park, remained completely unknown until recently. Its discovery is already being described by experts as a scientific milestone destined to reshape European paleontology and occupy researchers for decades to come.

From Chance Observation to Scientific Breakthrough

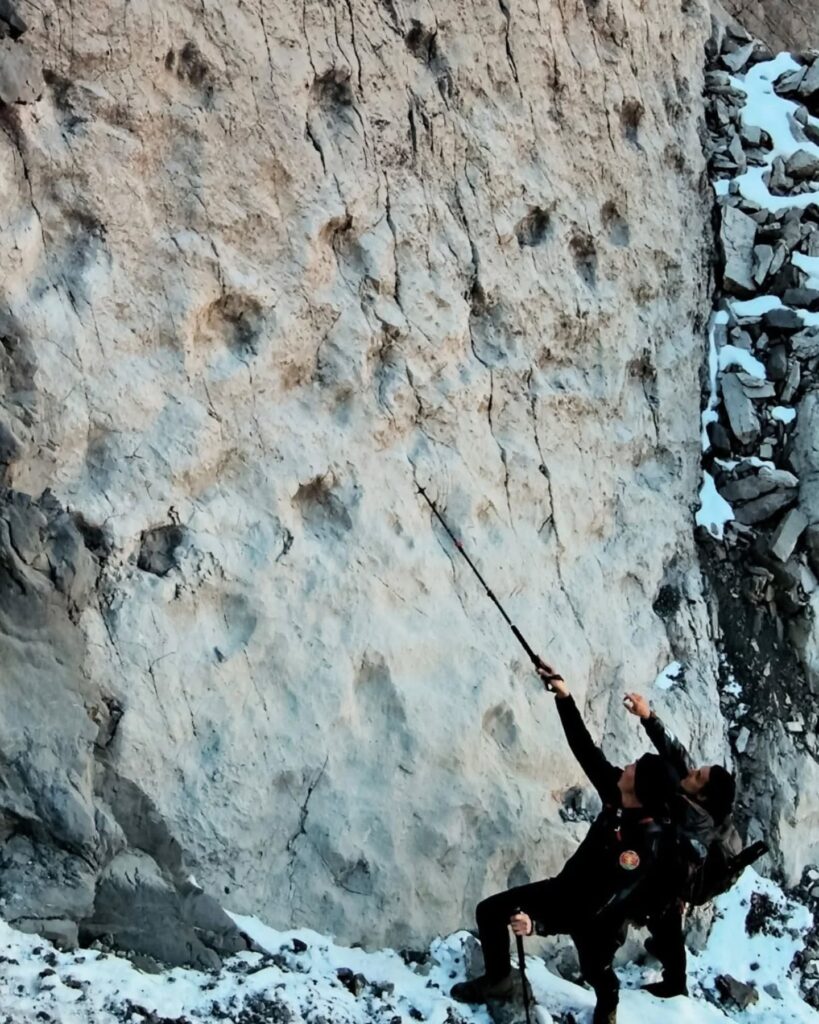

The story began in September 2025, when a nature photographer exploring the high-altitude landscapes of the Fraele Valley noticed unusual depressions aligned across pale rock walls. Viewed through binoculars, the markings appeared patterned and deliberate. After approaching the outcrop more closely, the photographer realized he was looking at fossilized footprints—dozens at first, then hundreds, and eventually thousands.

Within hours, the discovery was reported to Italian authorities responsible for cultural and paleontological heritage. The Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio immediately alerted the Directorate of Stelvio National Park, while leading paleontologists from the Natural History Museum of Milan were contacted to verify the find. Preliminary analysis confirmed what soon became undeniable: these were dinosaur tracks, preserved in remarkable detail and spread across an immense geological landscape.

A Landscape Frozen in the Late Triassic

Geological studies indicate that the footprints date back approximately 210 million years, to the Late Triassic period. At that time, the region that is now the central Alps bore no resemblance to today’s rugged mountains. Instead, it was part of a vast tropical carbonate platform near the shores of the ancient Tethys Ocean. Warm, shallow lagoons and tidal flats created ideal conditions for large dinosaurs to traverse soft, calcareous muds capable of recording every step.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Over millions of years, these sediments hardened into dolomite. Later, the colossal tectonic forces that formed the Alps uplifted and twisted the rock layers, rotating once-horizontal surfaces into near-vertical walls. As a result, dinosaur trackways that were once imprinted on flat coastal plains now appear suspended high above the valley floor, defying gravity and expectation.

Herds of Giants on the Move

The vast majority of the footprints belong to large herbivorous dinosaurs, most likely prosauropods—early relatives of the massive sauropods that would later dominate the Jurassic. Experts suggest that Plateosaurus, a long-necked dinosaur known from skeletal remains in central Europe, is the most probable trackmaker.

Many individual prints measure up to 40 centimeters in width, with clearly visible toes and claw impressions. In some areas, parallel trackways run side by side for hundreds of meters, offering compelling evidence that these animals moved together in herds. The range of footprint sizes suggests groups composed of individuals of different ages, providing rare behavioral insights into dinosaur social structure during the Triassic.

Occasionally, smaller impressions appear alongside the larger tracks, possibly representing forelimb support when animals paused or changed direction. Researchers have also noted the potential presence of other reptiles, including carnivorous dinosaurs or crocodile-like archosaurs, though further study is needed to confirm this.

An Alpine Site Unlike Any Other

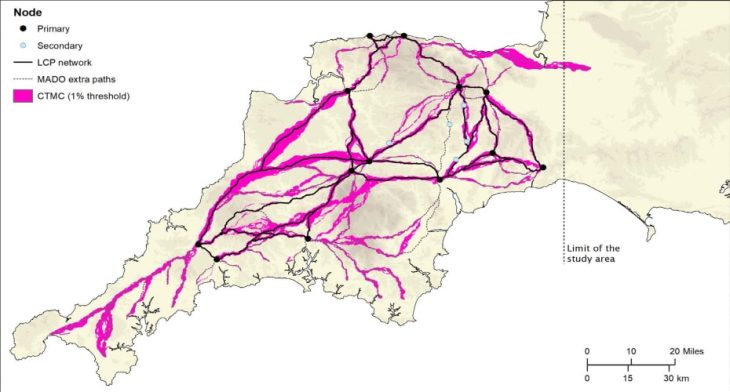

What sets this discovery apart is not only its sheer size but also its geological and geographic context. This is the first confirmed dinosaur tracksite ever found in Lombardy and the only one located north of the Insubric Line, one of the Alps’ most significant fault systems. Its position offers unique data on dinosaur distribution and paleogeography in what was once the northern margin of the ancient supercontinent Pangaea.

Preliminary surveys indicate an extraordinary density of tracks, in some places reaching up to six footprints per square meter. The track-bearing surfaces are distributed across at least seven ridgelines, spanning nearly five kilometers and involving dozens of superimposed rock layers. Around thirty separate outcrop areas have already been identified, with many more likely awaiting discovery.

Science, Protection, and the Future

Because the site is inaccessible by marked trails and located on fragile rock faces, researchers must rely heavily on drones, photogrammetry, and remote sensing technologies. These tools allow scientists to document the footprints without physically disturbing the surfaces, ensuring both accuracy and preservation.

Italian institutions have emphasized a threefold strategy moving forward: safeguarding the site, conducting long-term scientific research, and eventually finding ways to responsibly share its significance with the public. Formal collaboration between the Soprintendenza, Stelvio National Park, universities, and museums will underpin these efforts, with protection measures already underway.

A Discovery on the Eve of the Olympic Games

The timing of the find adds symbolic weight to its importance. The Fraele Valley lies close to areas that will host events during the Milan–Cortina 2026 Winter Olympic Games. While athletes prepare to compete on snow and ice, the surrounding mountains now tell a much older story—one of prehistoric giants traversing tropical shores under a Triassic sun.

This newly revealed “dinosaur valley” is more than a spectacular fossil site. It is a rare, intact snapshot of life on Earth at a pivotal moment in evolutionary history, preserved against all odds in the stone walls of the Alps. As research continues, it promises to rewrite key chapters of Europe’s prehistoric past, reminding us that even the most familiar landscapes may still conceal astonishing secrets beneath their surface.

Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano (Natural History Museum of Milan)

Cover Image Credit: Elio Della Ferrera, Arch. PaleoStelvio. Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano via Facebook