Recent archaeological excavations at Gradishte, near the village of Crnobuki in North Macedonia, have unveiled a significant ancient settlement that challenges previous assumptions about the site’s historical importance.

Initially thought to be a mere military outpost established to fend off Roman incursions, the findings suggest that Gradishte was, in fact, a thriving city with a rich cultural and economic life, predating the Roman Empire by centuries.

The research, conducted by a collaborative team from Cal Poly Humboldt and Macedonia’s Institute and Museum–Bitola, has revealed that the acropolis of Gradishte spans at least seven acres. This expansive area has yielded a wealth of artifacts, including stone axes, coins, a clay theater ticket, pottery, game pieces, and textile tools, all of which provide concrete evidence of a prosperous settlement dating back to at least 360 B.C.

Archaeologist Nick Angeloff has even posited that this site may represent the lost capital of the Kingdom of Lyncestis, an ancient polity established in the seventh century B.C.

“This discovery is significant,” Angeloff stated. “It highlights the complex networks and power structures of ancient Macedonia, especially given the city’s strategic location along trade routes to Constantinople. Historical figures such as Octavian and Agrippa may have traversed this area en route to confront Cleopatra and Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The site, first mentioned in literature in 1966, remained largely unexplored until recent years. Modern archaeological techniques, including ground-penetrating radar and drone-deployed LIDAR, have facilitated a deeper understanding of the settlement’s size and influence. The discovery of a coin minted during the lifetime of Alexander the Great (325-323 B.C.) has pushed back the timeline of the city’s establishment, suggesting human occupation may date back to the Bronze Age (3,300-1,200 B.C.).

Engin Nasuh, curator-advisor archaeologist at the National Institute and Museum–Bitola, emphasized the importance of these findings: “We’re only beginning to scratch the surface of what we can learn about this period. The discoveries not only illuminate North Macedonia’s past but also contribute to a broader understanding of ancient Western civilization.”

The artifacts unearthed at Gradishte, including charcoal and bone samples, have been dated between 360 B.C. and 670 A.D., indicating a long period of habitation and cultural development. This ancient Macedonian state, one of the earliest modern states in Europe, played a crucial role in shaping the political and cultural landscape of the region.

As the excavation continues, students, faculty, and researchers from both institutions are dedicated to uncovering the full story of this ancient city. Nasuh likened their efforts to assembling a large mosaic, where each new discovery adds a piece to the overall picture of early European civilizations.

“This ongoing work promises to reveal more about the intricate networks and vibrant culture of ancient Macedonia,” he concluded. “With each subsequent study, we are one step closer to understanding the complexities of our shared history.”

The findings at Gradishte not only reshape our understanding of North Macedonia’s historical narrative but also highlight the interconnectedness of ancient civilizations, offering valuable insights into the development of early European states and their lasting influence on the world.

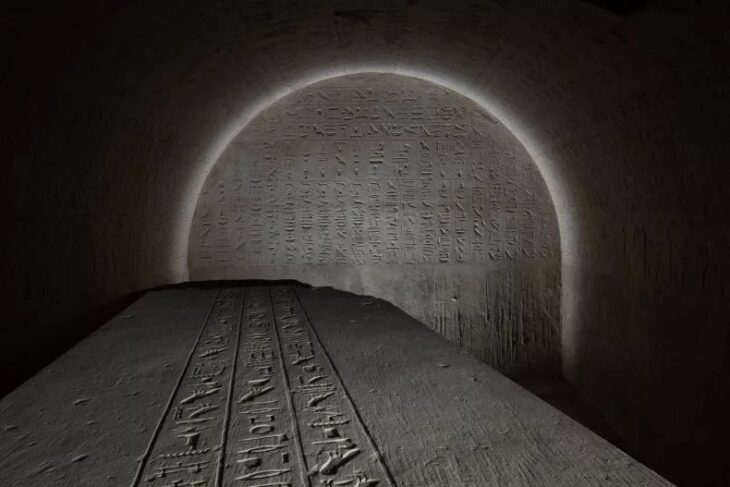

Cover Image Credit: Cal Poly Humboldt