An ancient Qin Dynasty inscription discovered on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau links the Kunlun legend to real geography, reshaping the western frontier of early Chinese history.

A newly authenticated stone inscription discovered on the windswept Qinghai-Xizang Plateau is reshaping the story of early Chinese civilization, revealing that the reach of the Qin Dynasty extended far deeper into the western highlands than previously believed. Known as the Garitang Engraved Stone, the relic records an imperial expedition ordered by Emperor Qin Shihuang in 210 BC, when envoys traveled toward the legendary Kunlun Mountains in search of medicinal herbs tied to the myth of immortality. Carved in small seal script and preserved near the northern shore of Gyaring Lake, the inscription provides rare, physical evidence of cultural interaction, geographical exploration, and cross-regional communication at the dawn of China’s imperial era.

Standing before the stone today, it is possible to imagine the moment it was created: weary court envoys guiding a carriage across the barren plateau after a long, freezing journey from the Qin capital of Xianyang, pausing beneath a rock shelter to carve their progress into the stone before pressing onward toward the sacred mountains. For more than two thousand years that brief message remained untouched, exposed to wind, snow, and silence, until researchers rediscovered it and confirmed that it was not legend, not rumor, but the authentic voice of a state-sponsored mission recorded at the highest altitude ever known for a Qin-era inscription.

Its significance lies not only in its dramatic setting, but in the story it tells. The inscription states that the envoy’s carriage had reached the site on the jimao day of the third month in the thirty-seventh year of Qin Shihuang’s reign, noting that the destination — Kunlun — lay one hundred and fifty li ahead. That single geographic reference transforms a mythic landscape into a traceable point on the historical map, placing Kunlun near the source region of the Yellow River and linking ancient cosmology to a real, navigable world. What had long existed in poetry, legend, and imagination now emerges through stone as evidence of lived movement across the plateau.

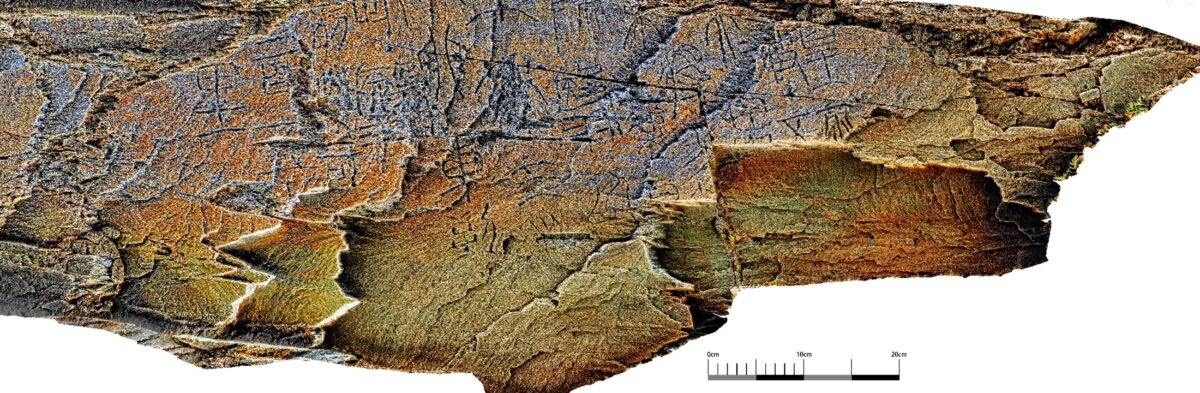

To verify the discovery, archaeologists and cultural heritage specialists carried out extensive multidisciplinary research at the site. Using high-precision photogrammetry, 3D modeling, and microscopic weathering analysis, they examined every groove, fracture, and chisel mark carved into the quartz sandstone surface. The tool traces matched Qin-period craftsmanship, the mineral deposits inside the characters showed long-term natural exposure, and the surrounding landscape revealed that the stone had remained in its original location since antiquity. Rather than a later imitation, the Garitang inscription stands as a genuine, undisturbed record from the final years of the Qin Empire.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Beyond its scientific confirmation, the stone challenges long-standing assumptions about how early China expanded and interacted with its frontier regions. The journey described in the inscription could not have been completed without cooperation from local plateau communities familiar with the terrain, climate, and routes. Instead of a one-sided imperial advance into an empty wilderness, the discovery points to shared navigation knowledge, exchange of guidance, and a cultural understanding shaped jointly by the Central Plains and the peoples of the highlands. The expedition to gather herbs from Kunlun becomes evidence not only of political ambition, but of communication, negotiation, and contact across landscapes.

It also reveals the early foundations of transportation networks that would later evolve into major trans-Asian routes. The reference to a carriage arriving at the lakeside site suggests the existence of structured paths and established passageways leading toward the Yellow River headwaters — the embryonic beginnings of routes that would eventually be known as the Qinghai branch of the Silk Road and the Tang-Xizang Ancient Road. Long before these roads were formally documented, the Garitang stone shows that movement, exchange, and mobility were already shaping the western frontier of the Qin world.

At the same time, the discovery breathes new life into the Kunlun myth itself. For millennia, Kunlun has symbolized the spiritual heart of Chinese cosmology — a sacred mountain associated with creation, immortality, and the meeting point between Heaven and Earth. The inscription marks a moment when that symbolic mountain crossed into geographical reality. It demonstrates that, by the late Qin period, Kunlun was not only imagined but actively sought, traveled toward, and integrated into state-level missions and imperial understanding. Myth and geography cease to stand apart; instead, they converge on the plateau in a way that reflects both belief and exploration.

The region surrounding the discovery further reinforces this continuity of human presence. During large-scale cultural relic surveys, dozens of archaeological sites were identified within a wide radius of the stone, spanning periods from the Paleolithic era to modern times. Far from being a desolate and untouched wilderness, the plateau emerges as a corridor of long-term settlement, migration, and interaction — a landscape crossed repeatedly by travelers, herders, and envoys across thousands of years.

Today, as the sun falls across the snow-covered peaks of the Three-River-Source region, the Garitang Engraved Stone stands as more than a fragment of the past. It is a turning point in historical understanding — a record that expands the western horizon of the Qin Dynasty, anchors the Kunlun legend in tangible reality, and reveals a civilization formed not only through unification, but through connection, movement, and shared cultural space. What began as a quiet inscription on an isolated rock has now become a landmark discovery, reshaping how the early story of China is seen, studied, and imagined.

Cover Image Credit: The Garitang Keshi, or the Garitang Engraved Stone. National Cultural Heritage Administration