A tiny copper-alloy object, long overlooked in a museum collection, is now transforming what archaeologists know about ancient Egyptian technology. New research led by scholars from Newcastle University and the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna reveals that Egyptians were using a mechanically sophisticated bow drill more than 5,300 years ago—far earlier than previously believed.

The study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Egypt and the Levant, identifies the artefact as the earliest known rotary metal drill from ancient Egypt, dating to the Predynastic period (late 4th millennium BCE), centuries before the first pharaohs ruled. The discovery pushes back the timeline for advanced drilling technology by more than two millennia.

A Forgotten Artefact Rediscovered

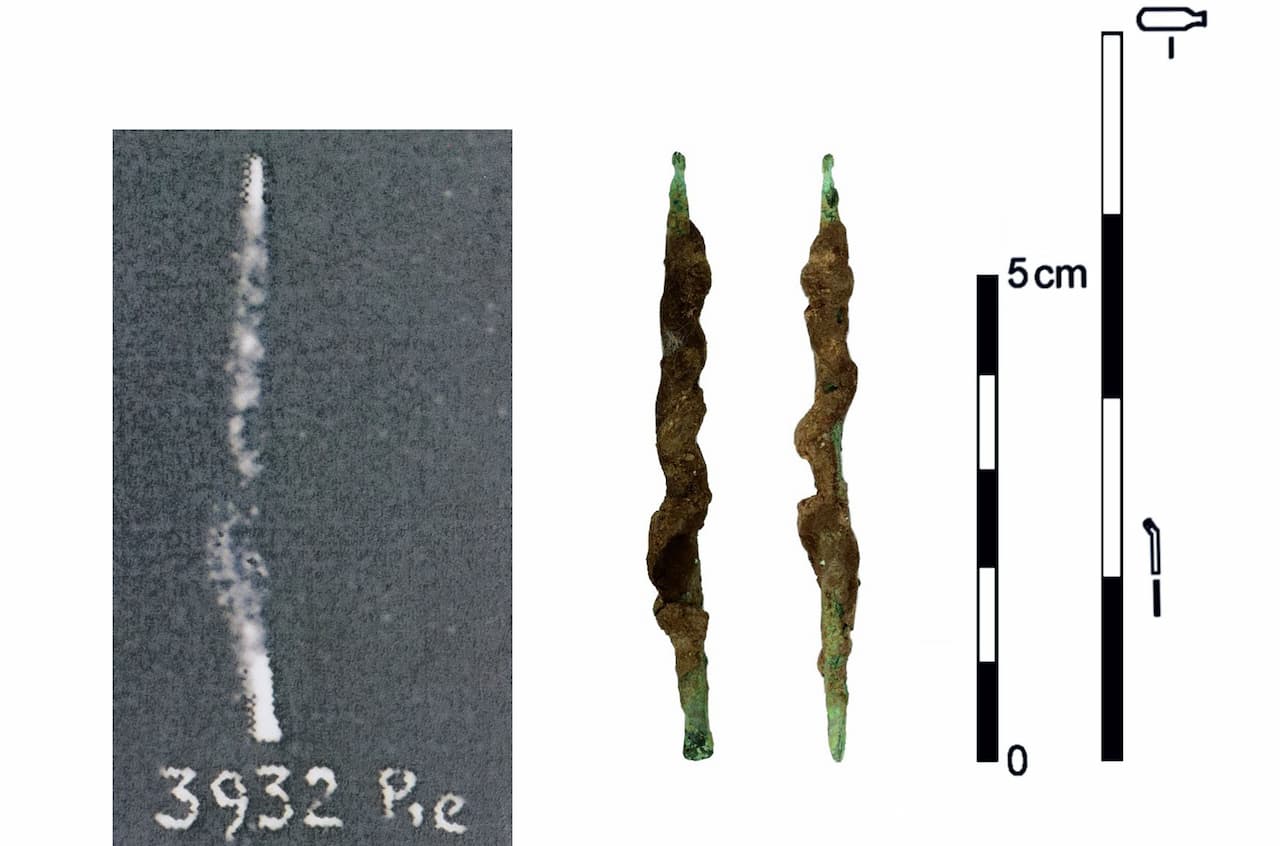

The object, catalogued as 1924.948 A in the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge, was excavated nearly a century ago from Grave 3932 at Badari, a cemetery site in Upper Egypt. The grave belonged to an adult man, and the tool itself is remarkably small—just 63 millimetres long and weighing approximately 1.5 grams.

When first published in the 1920s by archaeologist Guy Brunton, the artefact was briefly described as “a little awl of copper, with some leather thong wound round it.” That minimal description caused the object to fade into obscurity for decades.

However, modern re-analysis has revealed that this modest tool is anything but simple.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Clear Evidence of Rotary Drilling

Using microscopic examination, researchers identified distinctive wear patterns that could not have been produced by simple puncturing or scraping. Fine striations, rounded edges, and a slight curvature at the working tip all point to rotary motion, indicating that the tool was repeatedly spun during use.

Even more striking was the presence of six coils of an extremely fragile leather thong still wrapped around the shaft. According to the research team, this leather remnant is direct evidence of a bow drill mechanism, in which a string attached to a bow is wrapped around a drill shaft and moved back and forth to generate rapid вращение.

Dr Martin Odler, Visiting Fellow at Newcastle University and lead author of the study, explains that such tools were essential to early craftsmanship. “Behind Egypt’s famous stone monuments and jewellery were practical, everyday technologies that rarely survive archaeologically,” he says. “The drill was one of the most important tools, enabling woodworking, bead production, and furniture making.”

Thousands of Years Ahead of Its Time

Bow drills are well documented in later Egyptian periods, particularly during the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE). Tomb paintings from Luxor show craftsmen drilling beads and wood with bow-powered tools, and several complete drill sets from that era survive.

What makes the Badari find extraordinary is its age. The newly identified drill dates to Naqada IID, meaning Egyptians had mastered controlled, high-speed rotary drilling nearly 2,000 years earlier than previously evidenced by surviving tools.

This continuity suggests that the bow drill was not an experimental innovation, but a highly effective technology that endured for millennia.

An Unusual and Advanced Metal Alloy

The study also sheds new light on early Egyptian metallurgy. Using portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) analysis, the team discovered that the drill was made from a highly unusual copper-arsenic-nickel alloy, with notable amounts of silver and lead.

Co-author Jiří Kmošek notes that this composition would have produced a harder and visually distinctive metal than ordinary copper. “The presence of silver and lead may reflect deliberate alloying choices,” he explains, “or point to long-distance exchange networks and metallurgical knowledge linking Egypt to the wider Eastern Mediterranean.”

The findings raise intriguing questions about early resource procurement, trade routes, and underexplored ore sources in Egypt’s Eastern Desert during the fourth millennium BCE.

Big Discoveries in Small Objects

The research forms part of the UKRI-funded EgypToolWear project, which investigates wear traces on ancient Egyptian tools. Beyond rewriting technological history, the study highlights the untapped potential of museum collections.

A single artefact, described in one line a hundred years ago, has now provided rare evidence for both early metalworking and organic components—a combination that seldom survives in archaeological contexts.

“This object preserves not just the tool itself,” Dr Odler notes, “but also a trace of how it was used. That is incredibly rare for this period.”

Rewriting the History of Ancient Craftsmanship

The identification of the Badari bow drill fundamentally changes how scholars understand Predynastic Egyptian technology. It reveals a society that was already experimenting with complex mechanical solutions, advanced metallurgy, and efficient production techniques long before the rise of the pharaohs.

As researchers continue to re-examine forgotten artefacts with modern methods, more discoveries like this may still be waiting—quietly reshaping the story of humanity’s technological past.

Reference:

Odler, M., & Kmošek, J. (2025). The Earliest Metal Drill of Naqada IID Dating. Egypt and the Levant, Vol. 35. DOI: 10.1553/AEundL35s289

Cover Image Credit: Original photograph of the artefact published in 1927 by Guy Brunton (left) and the actual artefact, photo by Martin Odler. Newcastle University