Excavations at Tell el-Burak Reveal Technological Innovation and Early Sustainable Construction in Iron Age Lebanon

In a major archaeological breakthrough, researchers have identified the earliest known use of hydraulic lime plaster in Phoenician architecture—crafted not from volcanic ash like Roman concrete, but using recycled ceramic pottery. This discovery, made at the Iron Age site of Tell el-Burak in southern Lebanon, sheds light on ancient sustainability practices and high-level engineering previously unattributed to the Phoenicians.

The findings, published in Scientific Reports (2025), come from a multidisciplinary study of plaster samples collected from three installations, including a well-preserved wine press dating to ca. 725–600 BCE.

Ancient Wine Infrastructure Built with Recycled Pottery

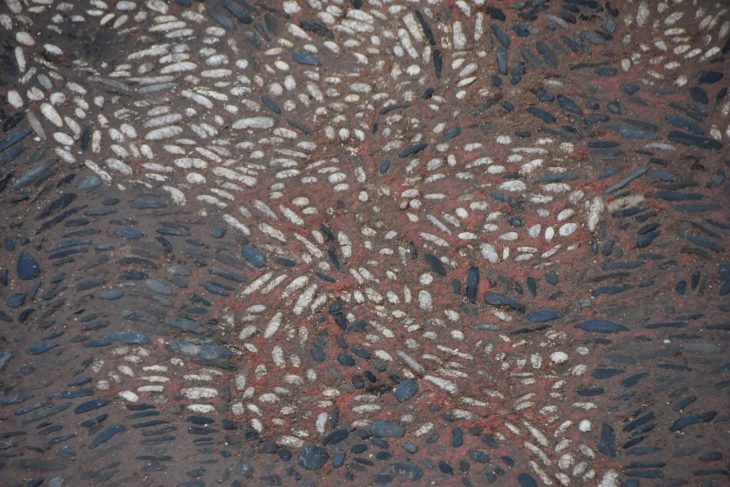

Located just 9 km south of Sidon, Tell el-Burak was a key agricultural hub for the Phoenician city-state. Among its most significant features is a massive wine press, consisting of a large grape treading basin connected to a 4,500-liter fermentation vat—both covered in a specialized lime-based plaster.

What made this plaster extraordinary was its composition: crushed ceramic fragments—likely broken amphorae—intentionally added to the lime binder. These ceramic inclusions acted as pozzolanic material, reacting chemically with the lime to form a hydraulic mortar—a material capable of setting and hardening in wet environments.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“The presence of ceramic aggregates wasn’t just about recycling waste—it was a technological choice to produce water-resistant, durable plaster,” says lead author Dr. Silvia Amicone.

This practice predates Roman concrete and aligns more closely with early Greek and Aegean technologies, though rarely seen in the Levant before now.

Scientific Evidence: A Multidisciplinary Approach

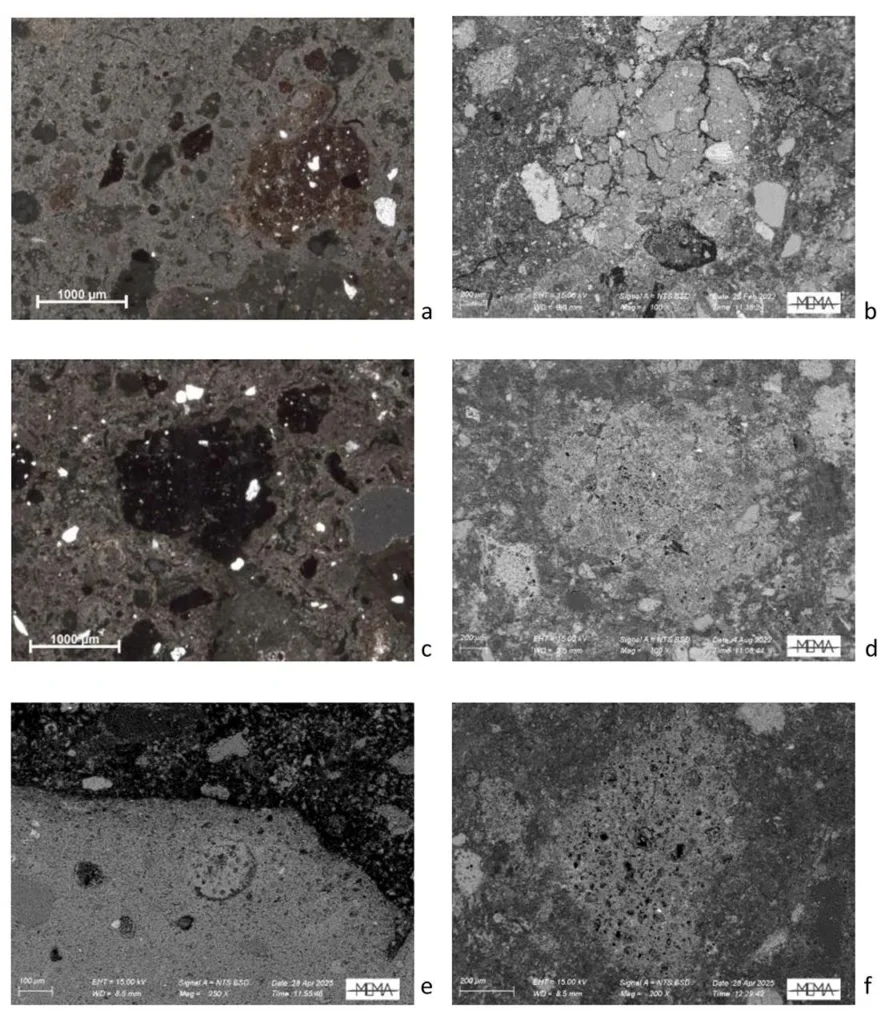

To confirm the hydraulic nature of the plaster, researchers applied a suite of scientific techniques, including:

Optical Microscopy & SEM-EDS: Identified chemical reaction rims between lime and ceramic, a hallmark of hydraulicity.

X-Ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD): Revealed mineral phases like gehlenite, cristobalite, mullite, and diopside, typically formed at high firing temperatures.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Showed bound water levels above 3% and CO₂ losses under 30%, confirming hydraulic classification.

Organic Residue Analysis (ORA): Detected sulphur compounds in the plaster—possibly tied to wine production or amphora use.

These results confirm that Tell el-Burak’s builders knew how to manipulate materials to create durable, water-resistant plasters, long before such knowledge became standardized in Roman construction.

Ceramic Waste as Strategic Resource

The ceramic fragments used in the plaster were not just construction debris. Petrographic and mineralogical analyses suggest they came from pottery production waste, likely from the nearby site of Sarepta, a known Phoenician ceramic center 4 km away.

Interestingly, these ceramic pieces show a mix of firing temperatures:

Type 1: Low-fired sherds (below 850°C), highly reactive.

Type 2: Overfired, vitrified pieces (above 1050°C), less reactive but still used.

Despite being more difficult to source and process, the presence of high-fired fragments suggests intentional selection or reuse of pottery wasters, not accidental inclusion. Moreover, no ceramic production waste has been found at Tell el-Burak itself, reinforcing the idea of specialist labor and material transport.

Technological Innovation with Centralized Control

This level of material knowledge, consistency, and effort points to centralized, elite-driven production. The plaster installations at Tell el-Burak reflect more than technical ingenuity—they also suggest an organized economic system, where specialists could access and transport specific materials for construction.

The use of such advanced plaster in wine production infrastructure also aligns with archaeological evidence that viticulture was a key component of the Phoenician economy, both locally and for trade.

Mediterranean Connections and Historical Significance

This discovery significantly shifts the timeline and geographic origin of hydraulic plaster technologies. It supports the idea that Phoenicians—known maritime traders and cultural transmitters—played a vital role in spreading technological innovations like pozzolanic mortars across the Mediterranean during the Iron Age.

While Roman concrete would later dominate ancient architecture, this early Phoenician example illustrates indigenous innovation and environmental adaptation long before the Romans industrialized the method.

Amicone, S., Orsingher, A., Cantisani, E. et al. Innovation through recycling in Iron Age plaster technology at Tell el-Burak, Lebanon. Sci Rep 15, 24284 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05844-x

Cover Image Credit: Reconstruction of the wine press at Tell el-Burak. Credit: A. Orsingher et al., Antiquity (2020)