Several meters beneath the restless waters off western France, archaeologists have uncovered the remains of a monumental stone construction that forces a fundamental rethink of Europe’s prehistoric coastlines. Near the Île de Sein, at the outer edge of Brittany, a massive submerged wall—built around 5800 BCE—now stands as one of the earliest known large-scale stone structures created by coastal hunter-gatherers in Atlantic Europe.

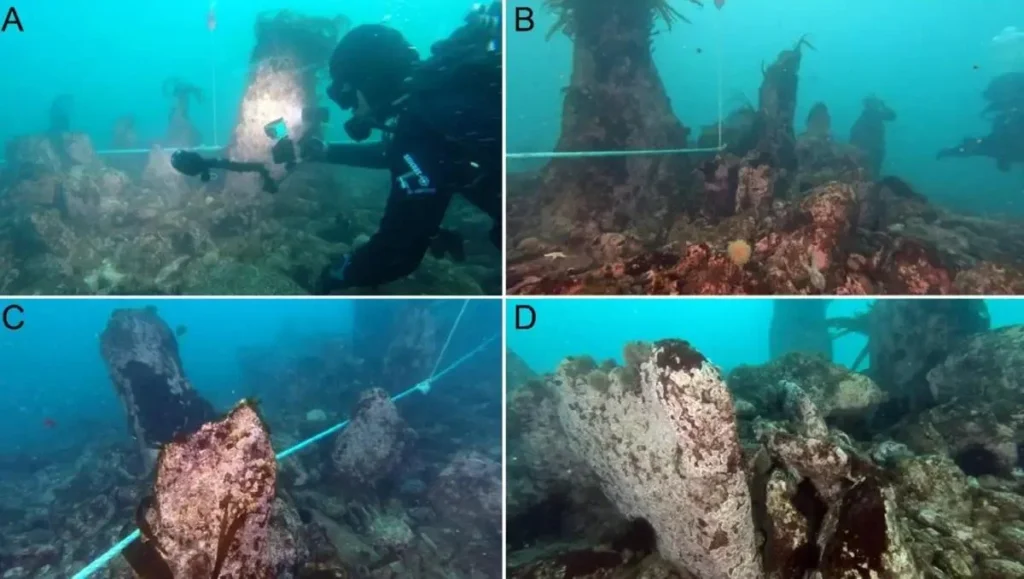

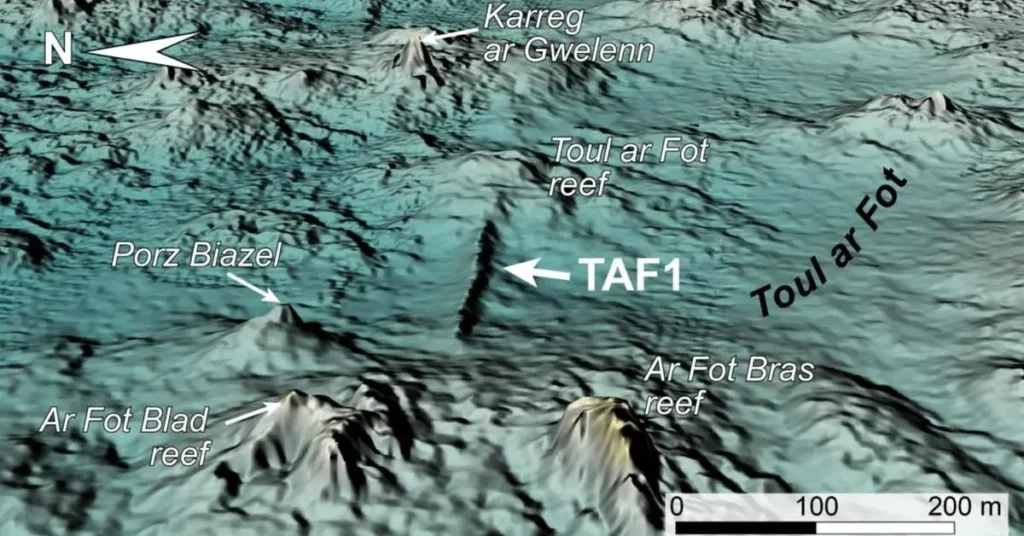

Stretching roughly 120 meters across a drowned valley, the wall lies at depths between seven and nine meters below today’s sea level. What first appeared as faint linear anomalies in seabed mapping has proven, after years of underwater investigation, to be a carefully engineered construction composed of stacked granite blocks reinforced with upright monoliths and vertical stone slabs. In places, these stones still rise nearly two meters high, locked in position despite more than seven millennia of marine erosion.

The discovery was initiated in 2017 through high-resolution LIDAR bathymetry, which revealed unnatural geometric forms on the seabed west of Sein Island. Subsequent dives carried out between 2022 and 2024 confirmed the human origin of at least eleven separate stone structures across the submerged plateau. Among them, the main wall—known as TAF1 by researchers—stands apart for its scale, complexity, and durability, unlike anything previously documented from this early period in France.

When the wall was built, the landscape looked radically different. Sea levels were several meters lower, and the now-submerged plateau formed a productive coastal environment shaped by tidal channels, rocky ridges, and shallow valleys. Archaeologists place the construction firmly within the transition from the Late Mesolithic to the Early Neolithic, a time when communities across Europe were beginning to experiment with new ways of organizing labor, resources, and territory.

What makes the Sein Island structures exceptional is not only their age but their engineering. The main wall is reinforced by more than sixty upright monoliths, arranged in parallel rows and anchored deeply into the bedrock. Between them, builders inserted vertical slabs and filled the structure with angular granite blocks, creating a broad, asymmetrical barrier designed to withstand powerful tidal currents and Atlantic swells. Some nearby structures follow similar principles, while others consist of narrower stone alignments made from smaller blocks.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Researchers believe that at least part of this submerged complex functioned as fish weirs—stone traps designed to funnel and capture fish with the rhythm of the tides. Such installations are known elsewhere in prehistoric Europe, but the Seine Island examples are larger, deeper, and architecturally more sophisticated than most previously recorded. Their construction would have required coordinated labor, detailed knowledge of tides and marine behavior, and long-term planning—traits once assumed to belong only to later farming societies.

Yet the sheer mass of the largest walls raises additional questions. Some scholars suggest that these structures may have served multiple roles, combining fishing with coastal protection or acting as territorial markers in a dynamic shoreline landscape. The walls’ unusual width and reinforced seaward sides hint at deliberate strategies to resist storm waves, suggesting that their builders were not merely exploiting the coast but actively shaping it.

The find also casts new light on the gradual rise of megalithic traditions in Brittany. The iconic standing stones and monumental tombs that would later define the region appear centuries after these submerged constructions were built. In this sense, the walls off Sein Island may represent an architectural precursor—a forgotten chapter in the long development of stone building along Europe’s Atlantic façade.

Local folklore adds an evocative layer to the discovery. Breton legends speak of a drowned land or lost settlement beyond the Bay of Douarnenez, swallowed by the sea in ancient times. While archaeologists caution against literal interpretations, they acknowledge that collective memories of vanished coastlines may echo real events experienced by prehistoric communities as rising seas slowly reclaimed inhabited landscapes.

Beyond France, the discovery contributes to a growing body of underwater archaeology reshaping views of Europe’s deep past. Similar submerged stone alignments have recently been documented in the Baltic Sea, where prehistoric groups engineered landscapes to manage animal migrations and marine resources. Together, these finds challenge long-held assumptions about the technological limits of hunter-gatherer societies.

As research continues, scientists plan to refine the dating of the Sein Island structures and search for further traces of settlement along the submerged coastline. Each new dive adds detail to a picture that is only beginning to emerge: a world where prehistoric people did not simply adapt to environmental change, but met it with ambition, planning, and stone.

Yves Fouquet, Jean-Michel Keroulle, Pierre Stéphan, Yvan Pailler, Philippe Bodénès, et al. Submerged Stone Structures in the Far West of Europe During the Mesolithic/Neolithic Transition (Sein Island, Brittany, France). International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, In Press. https://hal.science/hal-05406477

Cover Image Credit: A diver measures the height of an upright granite monolith on the submerged structure; the measuring rod visible in the image is 1 meter long. Photo credit: SAMM, 2023. Study by Yves Fouquet et al., International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (2025).