Long before numbers were written on clay tablets or calculations recorded in cuneiform, early farming communities in the Near East were already thinking mathematically—using flowers, symmetry, and painted pottery as their medium.

A new study published in the Journal of World Prehistory reveals that some of the world’s earliest botanical artworks, created more than 8,000 years ago, encode surprisingly advanced numerical and spatial concepts. Far from being simple decoration, these ancient plant motifs reflect an emerging understanding of order, proportion, and arithmetic long before formal mathematics existed.

Painted Plants in the World’s First Villages

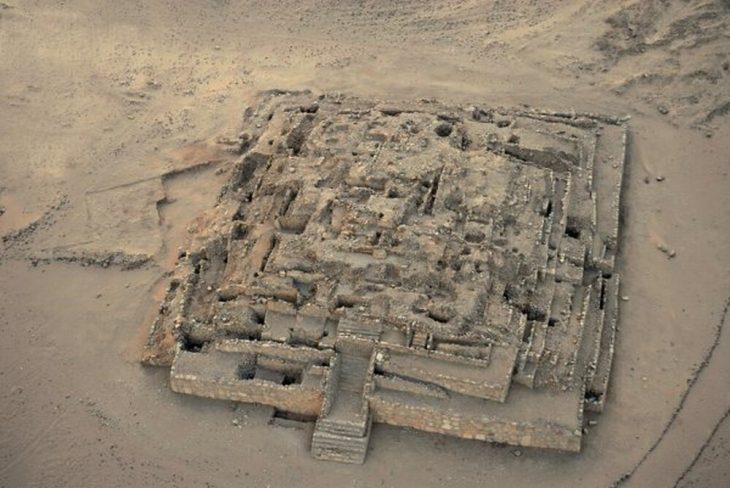

The research focuses on painted ceramic vessels produced by the Halafian culture, which flourished across northern Mesopotamia—today’s southeastern Turkey, northern Syria, and northern Iraq—between roughly 6200 and 5500 BCE. These communities lived in small agricultural villages, relying on collective labor, shared harvests, and carefully managed land.

Unlike earlier prehistoric art, which overwhelmingly favored animals and human figures, Halafian pottery shows a striking preference for plants. Flowers, shrubs, branches, and trees appear repeatedly on bowls, jars, and plates, often rendered with meticulous balance and symmetry.

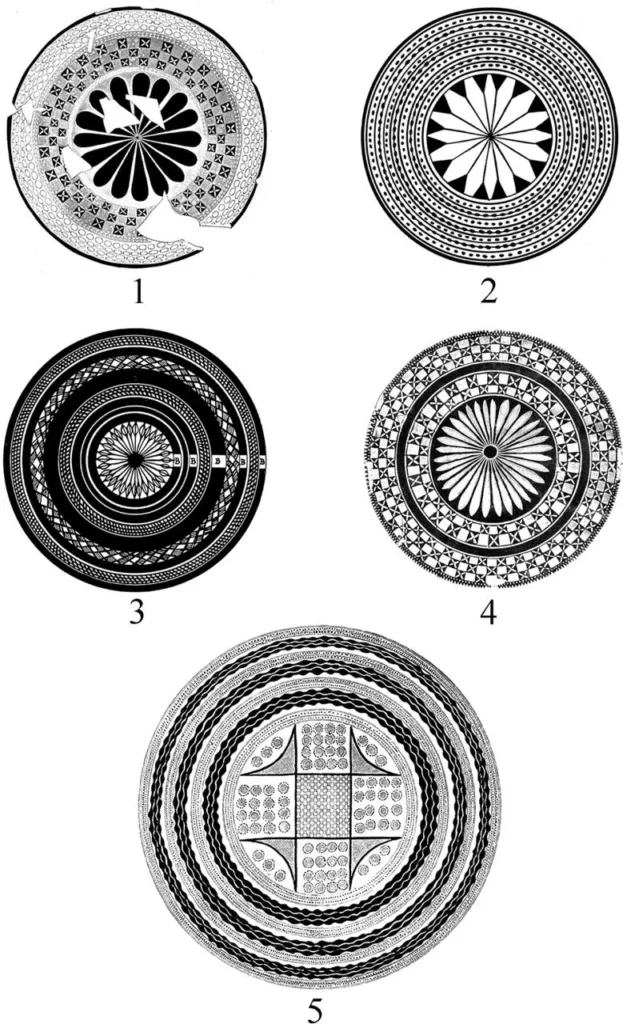

By compiling data from 29 archaeological sites and examining thousands of painted sherds, the researchers identified hundreds of vegetal motifs. While some resemble recognizable plant forms, many are highly stylized. What unites them is not botanical accuracy, but deliberate composition—suggesting a shared visual language rather than casual ornamentation.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Flowers That Count

The most revealing discoveries lie in how these plants were arranged.

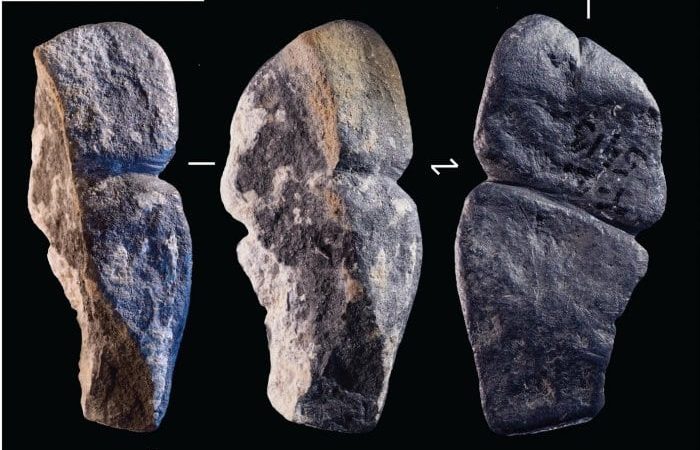

Many Halafian vessels feature large, centrally placed flowers whose petals are divided into precise numerical sequences. Repeatedly, the researchers documented flowers with 4, 8, 16, 32, and even 64 petals—numbers that form a clear geometric progression based on doubling. In one remarkable example, a bowl base was divided into a grid containing 64 individual flowers, each carefully positioned within the design.

Such patterns are unlikely to be accidental. Dividing circular space into equal segments requires careful planning, spatial reasoning, and consistency—key components of mathematical thinking. According to the study, these floral designs represent one of the earliest known expressions of arithmetic logic, predating writing by millennia.

Mathematics Before Writing

This evidence challenges long-held assumptions about the origins of mathematics. Traditionally, mathematical knowledge in Mesopotamia has been linked to later urban societies, where accounting, taxation, and administration demanded written numeracy.

The Halafian evidence tells a different story. Mathematical reasoning appears to have emerged organically from daily life in early farming villages. Dividing fields, allocating harvests, organizing communal labor, and maintaining fairness within small communities all required precise division and proportional thinking.

Pottery decoration, the researchers argue, provided a space where these cognitive skills could be explored visually. Symmetry, repetition, and numerical order became aesthetic principles as well as practical tools.

Why Flowers—and Not Crops?

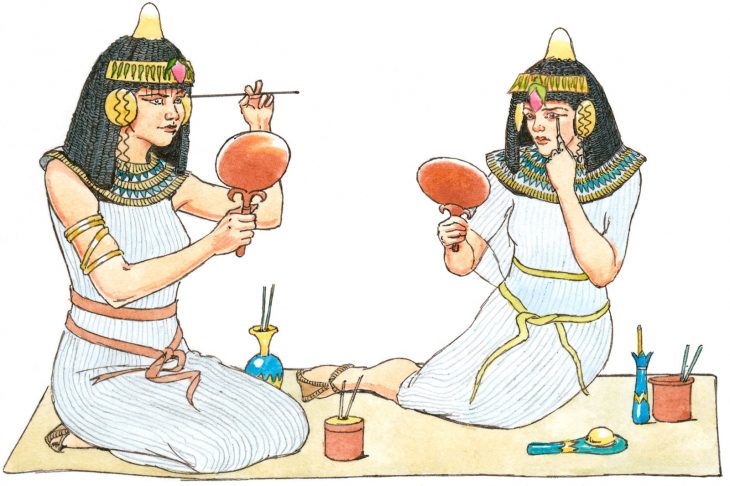

One of the study’s most intriguing observations is what doesn’t appear in Halafian art. Despite being agriculturalists, these communities did not depict staple crops such as wheat or barley. Instead, they favored flowers and trees—plants valued for their form rather than their utility.

This choice suggests that the motifs were not tied to fertility rituals or agricultural magic. Instead, the authors propose that flowers were chosen for their emotional and sensory impact. Modern psychological research shows that symmetry and floral forms tend to elicit positive emotional responses—a reaction that may have deep evolutionary roots.

In this light, Halafian pottery emerges as both intellectual and emotional expression: an early fusion of beauty, order, and cognition.

Rethinking the History of Numbers

By linking prehistoric art to early numerical reasoning, the study pushes the history of mathematics far deeper into the human past. Mathematical thinking did not suddenly appear with writing and bureaucracy; it developed gradually through visual practices embedded in everyday life.

The Halafian artisans were not mathematicians in the modern sense. Yet their ability to divide space, repeat patterns, and consistently apply numerical structures reveals a sophisticated cognitive world—one in which art, agriculture, and mathematics were deeply intertwined.

Eight thousand years ago, long before numbers had names, humanity was already counting—petal by petal.

Garfinkel, Y., Krulwich, S. The Earliest Vegetal Motifs in Prehistoric Art: Painted Halafian Pottery of Mesopotamia and Prehistoric Mathematical Thinking. J World Prehist 38, 14 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-025-09200-9

Cover Image Credit: Public Domain