Archaeologists uncover forgotten Chinese cowboys in Eastern Oregon, revealing how Chinese immigrants shaped ranching, buckaroo culture, and the American West.

For generations, the image of the American cowboy has been shaped by movies, novels, and popular culture — rugged white men riding horses across endless plains. But new archaeological research in Eastern Oregon is challenging that narrow vision, uncovering compelling evidence that Chinese immigrants played a vital and long-overlooked role in the ranching history of the American West.

Recent investigations have now linked Chinese Americans to more than 30 historic ranches across Eastern Oregon, including the remote Stewart Ranch in Grant County. These discoveries are the result of a collaborative effort between the Southern Oregon University Laboratory of Anthropology (SOULA), the Oregon Historical Society, and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), with support from the Roundhouse Foundation.

A Remote Ranch Preserved in Time

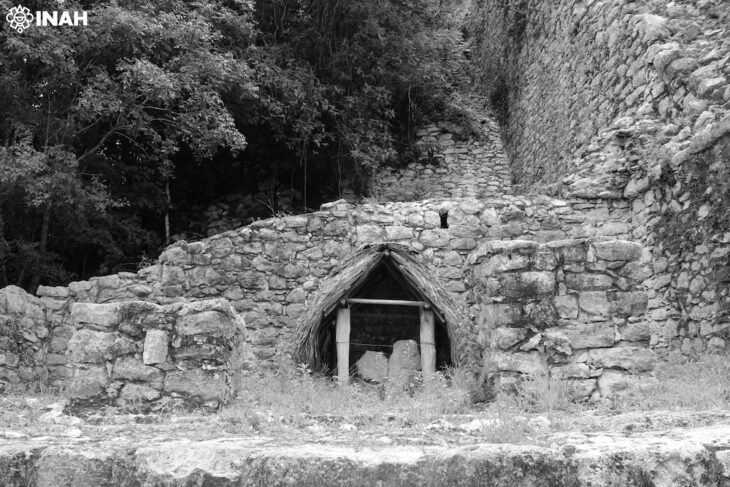

Stewart Ranch lies deep within the Phillip W. Schneider Wildlife Area, accessible only by rugged dirt roads. Its isolation has proven to be a gift for archaeologists, preserving structures and landscapes much as they appeared in the early 20th century.

“It feels like going back in time,” said Chelsea Rose, director of SOULA, who described the site as unusually intact compared to many historic ranches altered by modern development.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

During a hot and dusty week in July 2025, archaeologists, students, and community volunteers carefully excavated compacted soils around historic bunkhouses and work areas. Their goal was to uncover physical traces of Chinese cowboys and cooks whose lives were only faintly recorded in written history.

Chinese Cowboys Hidden in Plain Sight

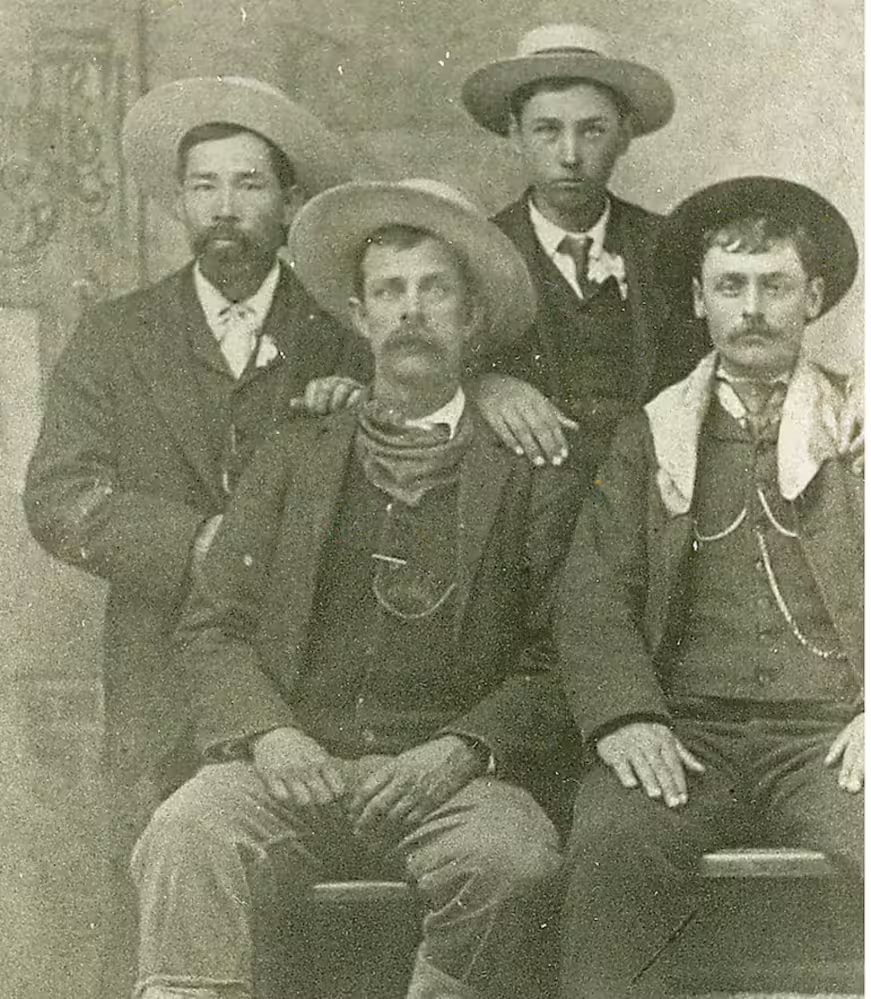

The excavations shed new light on individuals such as Buckaroo Sam, Jim Lee, Fon Chung, Markee Tom, Hi Moon, and Tom Lim — Chinese American men who worked as cowboys, cooks, sheepherders, foremen, and even ranch owners.

Buckaroo Sam, one of the most well-documented figures, was praised in his 1935 obituary as “one of the best horsemen” in Eastern Oregon. Known for his red handkerchief and expert roping skills, Sam embodied the buckaroo tradition — a regional form of cowboying rooted in California and the Great Basin.

Jim Lee, another key figure at Stewart Ranch, gained a reputation as a remarkable cook. Oral histories describe him as “particularly good with desserts,” while later archaeological evidence suggests his specialty may have included mutton stews and communal meals that sustained ranch crews after long days of labor.

Artifacts That Tell Everyday Stories

Rather than dramatic treasures, archaeologists uncovered the small, telling objects of daily life: buttons, jean rivets, broken dishes, glass bottle fragments, spent ammunition, and animal bones.

Zooarchaeologist Katie Johnson identified bones from beef, deer, and medium-sized mammals consistent with sheep. These findings align with historical accounts of shared meals and stews prepared to feed groups of working ranch hands.

“These are the kinds of artifacts that reveal how people lived together, worked together, and supported each other,” Johnson explained.

Importantly, researchers emphasize that the absence of artifacts made in China does not diminish Chinese presence. Many of these men lived in Oregon for decades, purchasing goods locally and adapting their material culture to what was available.

Rewriting the Cowboy Myth

The discoveries at Stewart Ranch are part of a broader effort to dismantle the myth of the American cowboy as a singular, white figure. Historians estimate that as many as one in four cowboys in the American West were Black, while the roots of cowboy culture itself trace back to Mexican vaqueros of the 18th century.

Chinese cowboys, however, were largely erased from this narrative — not because they were absent, but because systemic racism and exclusionary laws prevented them from passing down family histories or securing their place in official records.

Dale Hom, a retired forester and artist, has been instrumental in restoring visibility to these pioneers. His illustrated work, “They Called Him… Buckaroo Sam,” published in the Oregon Historical Quarterly, blends historical research with personal experience to reimagine Chinese cowboys within the Western landscape.

The Oregon Chinese Diaspora Project

Stewart Ranch is just one focus of the Oregon Chinese Diaspora Project (OCDP), a grassroots, multi-agency initiative dedicated to documenting early Chinese American life in rural Oregon.

The project relies heavily on partnerships with local communities, including the Grant County Ranch and Rodeo Museum and the Kam Wah Chung State Heritage Site. These relationships help researchers connect archaeological evidence with oral histories, family archives, and regional memory.

As artifacts are cleaned, cataloged, and analyzed in university labs, researchers continue to scour historic newspapers, photographs, and censusrecords. The work is meticulous and time-consuming, but its impact is profound.

Restoring a Lost Chapter of American History

In the late 1800s, Chinese Americans made up more than 40% of Grant County’s population. By 2020, less than 1% of residents reported Asian ancestry — a dramatic decline driven by decades of discrimination and exclusion.

Yet the legacy of those who remained endures. Jim Lee left his estate to the Catholic Home in Baker City. Buckaroo Sam spent his final years helping a hotel-owning family in John Day after losing his home in a devastating fire.

“These stories add richness and depth to Oregon history,” Rose said. “They don’t take anything away from other ranching families — they make the story more complete.”

As archaeologists, artists, and community historians continue their work, a fuller picture of the American West is emerging — one that finally recognizes Chinese cowboys not as footnotes, but as integral figures in the making of the frontier.

“The more we uncover,” Hom reflects, “the more it expands what it truly means to be an American cowboy.”

Oregon Public Broadcasting (OPB)

Cover Image Credit: Southern Oregon University Laboratory of Anthropology; Kam Wah Chung State Heritage Site