By combining epigraphy, linguistics, and historical analysis, new research suggests that the mysterious ancient Iberian language may be more closely related to Basque than previously believed.

For centuries, the origin of the Basque language has puzzled linguists. Spoken today in parts of northern Spain and southwestern France, Basque (Euskara) is famously unrelated to any known Indo-European language. Now, a new scientific study led by Eduardo Orduña Aznar of the University of Barcelona is shedding fresh light on this mystery by uncovering potential connections between Basque and the ancient Iberian language, once spoken across much of the Iberian Peninsula before Romanization.

What makes this research particularly significant is that it moves beyond the well-known similarities in number systems and explores a deeper, more meaningful layer of language: kinship terms and personal designations. These findings suggest that Basque and Iberian may share a remote common origin rather than being linked by coincidence or simple cultural contact.

A Longstanding Linguistic Debate Revisited

The idea that Iberian and Basque might be related is not new. As early as the 16th century, historians such as Ambrosio de Morales speculated about a connection. In the 19th century, linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt argued that Iberian peoples and Basque speakers were historically linked, based largely on place names.

However, enthusiasm for this theory, known as Basque-Iberianism, declined sharply in the 20th century. Once scholars deciphered the Iberian script, it became clear that Basque could not directly translate Iberian inscriptions. As a result, many modern linguists dismissed any genetic relationship between the two languages.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Orduña’s work represents a revival of a more cautious and evidence-based version of Basque-Iberianism, grounded in internal textual analysis rather than speculation.

The Breakthrough That Started with Numbers

The strongest evidence for a connection emerged in the early 2000s with the decipherment of the Iberian numeral system. Research by Orduña and later expanded by Joan Ferrer i Jané revealed that Iberian numerals closely mirror Basque ones, both in form and structure.

Examples include:

Iberian ban (one) and Basque bat

Iberian bi (two) and Basque bi

Iberian laur (four) and Basque lau

Iberian borste (five) and Basque bost

Iberian orkei (twenty) and Basque hogei

Even more striking is how these numbers combine. Iberian orkeiborste (25) follows the same logic as Basque hogei ta bost (“twenty and five”). These forms appear in practical contexts such as weights and measures, leaving little doubt about their meaning.

Because numbers are part of a stable and conservative vocabulary, many scholars see this level of similarity as strong evidence of a genetic relationship.

Beyond Numbers: Family Ties in Language

In his latest study, Orduña asks a logical next question: if Iberian and Basque are related, should we not find similarities in other core vocabulary? He focuses on kinship terms, such as “father,” “son,” and “relative,” which are ideal candidates because they are culturally central and linguistically stable.

Using a rigorous contextual method, Orduña identifies repeated elements in Iberian inscriptions that do not behave like typical personal names. These elements appear frequently, combine with each other, and often occur in funerary or dedicatory texts.

For example, in a lead inscription from Castellón, sequences like aur, uni(n), aste, and be(i) recur in ways that suggest meaningful lexical elements rather than names. Orduña compares these with Basque and ancient Aquitanian (an early relative of Basque) forms:

ata- possibly linked to Basque aita (“father”)

uni(n)- comparable to Basque unide (“wet nurse” or family helper)

-kidei- resembling Basque -(k)ide, meaning “companion” or “member of”

-be- paralleling Aquitanian elements found in words meaning “son” or “child”

-ko and -so, similar to Basque kinship suffixes as in izeko (“aunt”) or aitaso (“grandfather”)

Crucially, these elements tend to form a distinct subgroup within Iberian inscriptions, much like numerals do, reinforcing the idea that they belong to a shared semantic system.

Grammar, Verbs, and New Archaeological Evidence

The study also highlights grammatical similarities. Iberian appears to use a suffix -en to mark possession, comparable to the Basque genitive -en. Another suffix, -te, may function similarly to the Basque ergative marker, a rare grammatical feature in Europe.

Verbal forms offer further parallels. Iberian terms such as egiar or ekiar, possibly meaning “made,” resemble Basque egin (“to make”). These similarities suggest not just shared words, but shared grammatical structures.

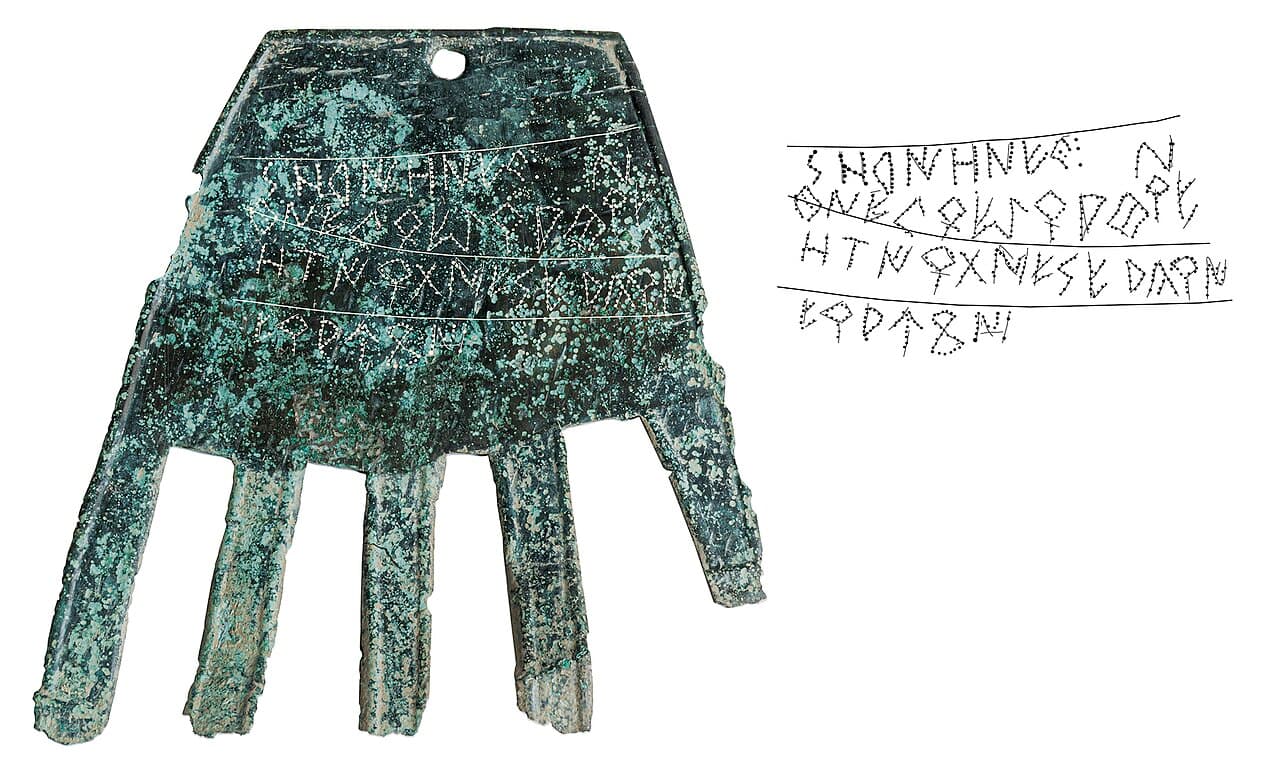

Recent archaeology adds weight to the argument. The discovery of the Bronze Hand of Irulegi in Navarre revealed a Vasconic (early Basque) inscription written using an adapted Iberian script. One verb on the artifact, efaukon, closely resembles an archaic Basque form meaning “he/she gave,” and mirrors Iberian verbal forms found elsewhere.

A Cautious but Compelling Conclusion

Orduña is careful not to overstate his case. Iberian remains only partially understood, and some proposed sound correspondences are still debated. Yet the accumulation of evidence—from numerals and kinship terms to morphology and inscriptions—points in a consistent direction.

Rather than isolated coincidences, the similarities between Iberian and Basque form interconnected systems that repeatedly align with one another. As Orduña concludes, exclusive and systematic parallels of this kind cannot be ignored.

Piece by piece, the linguistic puzzle of pre-Roman Iberia may finally be coming together, offering new insight into the deep history of one of Europe’s most enigmatic languages.

Orduña Aznar, E. (2026). The relationship between Basque and Iberian: Beyond the numerals. Palaeohispanica, 25(1) (Actas del XV Coloquio de Lenguas y Culturas Paleohispánicas). https://doi.org/10.36707/palaeohispanica.v25i1.690

Cover Image Credit: Irulegi’s hand and his inscription. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons