Researchers from the University of Bristol are rewriting the history of paleontology’s darkest and most bizarre event.

Vandals with sledgehammers destroyed skeletons and models intended for display in New York’s first dinosaur museum before it was even finished in 1871.

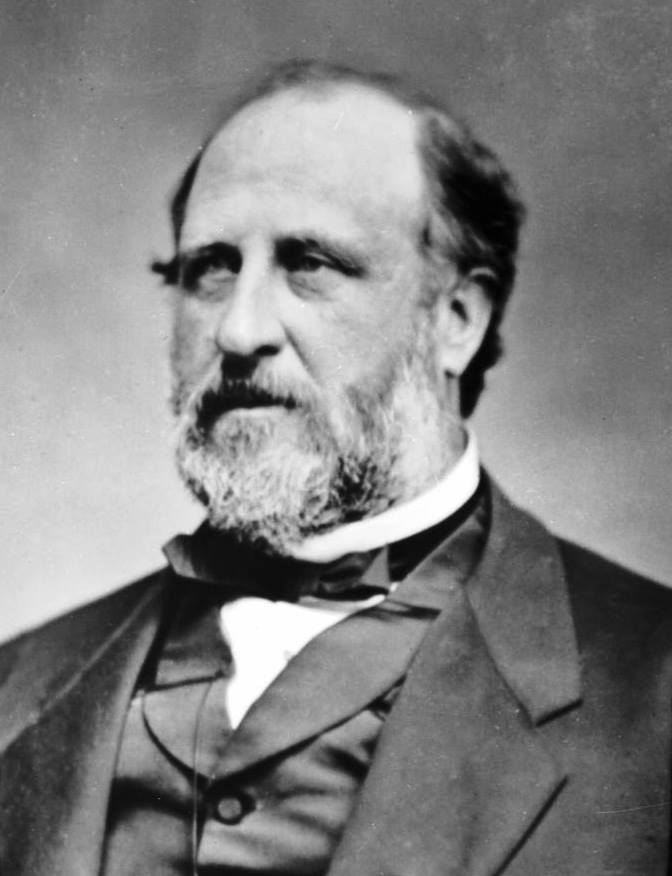

For more than a century, historians believed William “Boss” Tweed, New York’s most powerful political figure at the time, was to blame. But now researchers have revisited the crime — and point to a new suspect in what they call the “greatest act of vandalism in the history of dinosaur study.”

However, a recent paper by Victoria Coules of Bristol’s Department of History of Art and Professor Michael Benton of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences sheds new light on the incident and, in contrast to earlier accounts, identifies who was actually behind the order and what drove them to such wanton destruction—an odd man by the name of Henry Hilton, the Treasurer and VP of Central Park.

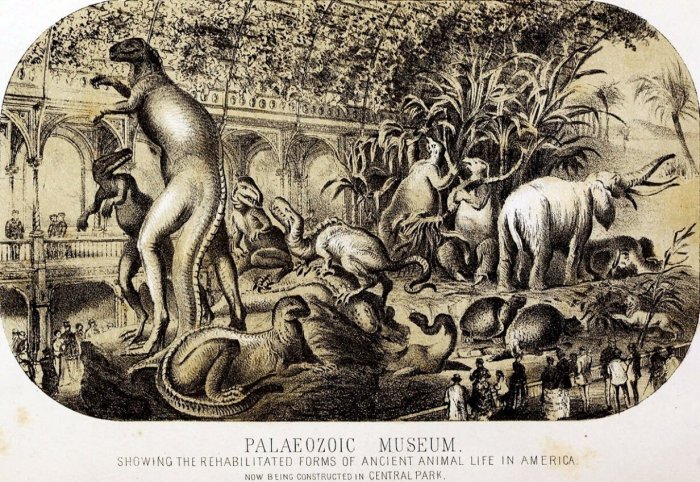

Paleontology was still in its infancy in 1871, and new discoveries made all over the world stoked curiosity about the enormous extinct animals. The Paleozoic Museum was to feature the work of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, an English natural history artist who galvanized interest in dinosaurs in the United States with the display of the world’s first mounted dinosaur skeleton in Philadelphia in 1868.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Hawkins used fossil evidence to create full-sized models for elaborate dioramas in preparation for the New York Museum. However, the museum was canceled in 1870 by the Tweed-controlled Central Park board. Vandals destroyed all of Hawkins’ models, casts, and studio a few months later.

“It’s all to do with the struggle for control of New York City in the years following the American Civil War (1861-1865),” said Victoria Coules. “The city was at the center of a power struggle—a battle for control of the city’s finances and lucrative building and development contracts.”

As the city grew, the iconic Central Park was taking shape. More than just a green space, it was to have other attractions, including the Paleozoic Museum.

Professor Benton explains, “Previous accounts of the incident had always reported that this was done under the personal instruction of ‘Boss’ Tweed himself, for various motives from raging that the display would be blasphemous, to vengeance for a perceived criticism of him in a New York Times report of the project’s cancelation.”

“Reading these reports, something didn’t look right,” Coules said. “At the time Tweed was fighting for his political life, already accused of corruption and financial wrong-doings, so why was he so involved in a museum project?” She added, “So we went back to the original sources and found that it wasn’t Tweed—and the motive was not blasphemy or hurt vanity.”

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) and the Central Park Zoo were two additional projects in Central Park that were simultaneously under construction, which complicated the situation. But, as Professor Benton explained, “drawing on the detailed annual reports and minutes of Central Park, along with reports in the New York Times, we can show that the real villain was one strange character by the name of Henry Hilton.”

Coules adds, “Because all the primary sources are now available online, we could study them in detail—and we could show that the destruction was ordered in a meeting by the real culprit, Henry Hilton, the Treasurer and VP of Central Park—and it was carried out the day after this meeting.”

Professor Benton concluded, “This might seem like a local act of thuggery but correcting the record is hugely important in our understanding of the history of paleontology. We show it wasn’t blasphemy, or an act of petty vengeance by William Tweed, but the act of a very strange individual who made equally bizarre decisions about how artifacts should be treated—painting statues or whale skeletons white and destroying the museum models. He can be seen as the villain of the piece but as character, Hilton remains an enigmatic mystery.”

Hilton was already notorious for other eccentric decisions. When he noticed a bronze statue in the Park, he ordered it painted white, and when a whale skeleton was donated to the American Museum of Natural History, he had that painted white as well. Later in life, other ill-judged decisions included cheating a widow out of her inheritance, squandering a huge fortune, and trashing businesses and livelihoods along the way.

Cover Photo: Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’s workshop with his mounted skeletons and life-size restorations of dinosaurs and other animals. (Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins Album/Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia)