New research reveals that Neolithic shell trumpets from Catalonia served as the earliest long-distance communication system in the Iberian Peninsula.

When Neolithic miners descended into the dark, twisting galleries of the variscite mines at Gavà more than 6,000 years ago, they did not rely solely on torches or shouted voices to coordinate their labour. According to a new study published in Antiquity, they also used powerful shell trumpets fashioned from Mediterranean sea snails, capable of projecting blasts as loud as a modern ambulance siren. The research identifies these instruments—twelve in total—as the earliest long-distance communication devices ever documented in northeastern Iberia.

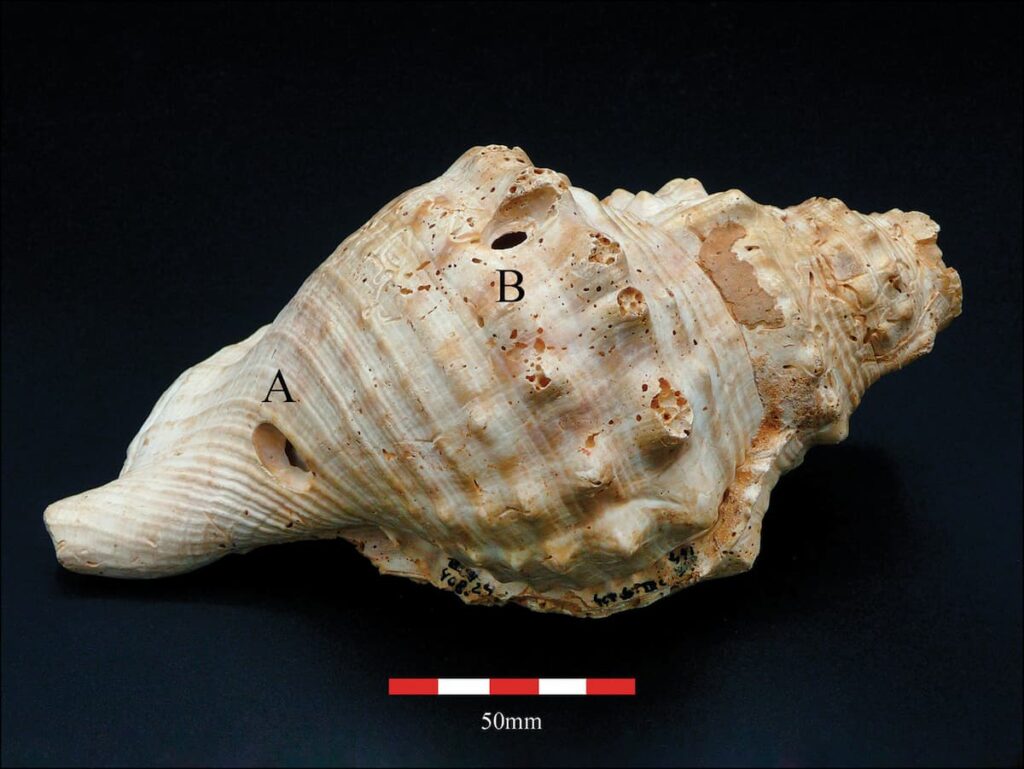

The shells themselves came from Charonia lampas, a large marine gastropod known as the “triton.” Today the species is rare; in the Neolithic, it lived at depths below five metres in the Mediterranean. Yet these shells appear at five inland archaeological sites—Mas d’en Boixos, Cal Pere Pastor, Cova de l’Or, Espalter, and, most remarkably, the mines of Can Tintorer—an early indication that they were deliberately collected, circulated, and transformed into instruments rather than scavenged as food waste. Biological marks inside the shells confirm that most were gathered after the animals had died, specifically for crafting tools of sound.

A Clustered Tradition Spanning More Than a Millennium

The distribution of the twelve instruments is strikingly tight. They all come from a relatively small area in Catalonia—the Penedès plain and the Llobregat basin—regions linked by river networks and dense Neolithic settlement. Radiocarbon data places them between 4500 and 3500 BCE, coinciding with the Postcardial and Middle Neolithic periods. This geographic clustering, argue researchers Miquel López-García and Margarita Díaz-Andreu of the University of Barcelona, suggests a deeply rooted regional sound tradition, maintained and transmitted over many generations.

At Mas d’en Boixos, two of the horns were found in refuse pits; a third was placed near five contemporaneous burials, hinting at a ritual or symbolic dimension. In Cova de l’Or, a well-preserved shell lay within layers dating to the Epicardial–Middle Neolithic transition, found alongside human skull fragments whose relationship to the trumpet remains unclear. But the most intriguing context lies at Can Tintorer, a subterranean mine network famous for its extraction of variscite—a green mineral used to create ornaments circulated across Neolithic Europe. Six shell horns were discovered in refilled mine shafts, firmly dated to 4050–3650 BCE.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Acoustic Power That Reaches Beyond the Horizon

Of the twelve shell trumpets, eight still function. Under supervision from museum conservators, López-García—himself a professional trumpet player—performed controlled acoustic tests. The results were astonishing.

Seven of the eight instruments exceeded 100 decibels at one metre, reaching a peak of 111.5 dBA, roughly the intensity of an emergency siren. This makes them the most powerful prehistoric sound instruments known in the region, and almost certainly capable of carrying controlled signals across several kilometres of open landscape.

Such performance would have been invaluable in Neolithic Catalonia—a region of growing agricultural settlement and intensifying mining activity. Sites like Mas d’en Boixos and Cal Pere Pastor lie only five kilometres apart. A shell blast from one ridge could easily have been heard on another.

Inside the Can Tintorer mines, where shafts extend deep underground with limited visibility and limited airflow, a single trumpet could have coordinated work teams, signalled danger, or communicated between miners at the surface and those below.

The study therefore proposes a compelling scenario: these horns formed a structured, long-distance signalling network, used to orchestrate labour, maintain safety, or announce movement between communities.

Music Built Into the Bones of the Shell

Despite their raw acoustic force, the trumpets were not merely utilitarian. The best-preserved specimens, with carefully cut apices measuring around 20 mm, produced up to three stable notes: the fundamental frequency, its octave, and an octave-plus-fifth. The tones fall between 395 and 471 Hz—roughly G4 to A#4—a register considerably higher than shell trumpets known from South America, Asia, or other parts of Europe.

Techniques like hand-stopping and note bending could further modulate pitch, enabling an experienced musician to create expressive phrases, though at the cost of losing intensity. In other words, Neolithic communities may have used the same instrument to summon people across valleys and to perform during rituals, gatherings, or ceremonies.

The Mystery of the Holes

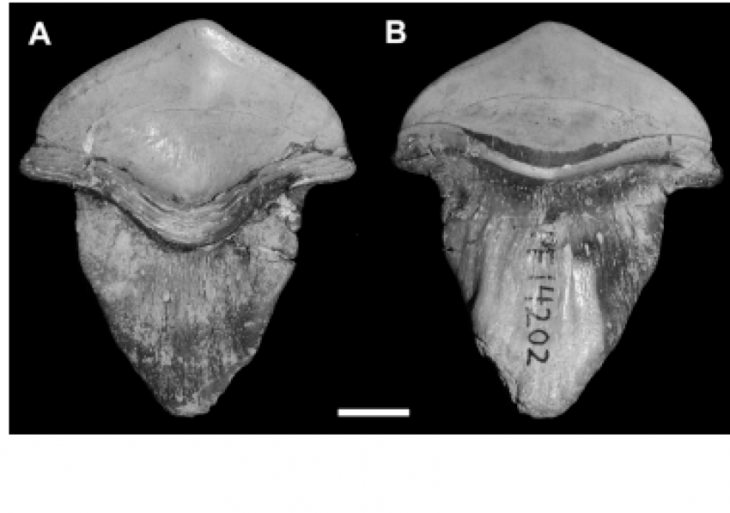

Several shells carry holes in their final whorl. For years, archaeologists debated whether these were suspension points or tone holes. Acoustic tests now resolve the question: they were neither.

Covering or uncovering the holes produced no change in pitch, ruling them out as tuning devices. But the impact on loudness was significant: in one Gavà specimen, the holes caused a 7.6 dBA loss in sound power—a level of deterioration inconsistent with intentional design. Their irregular shape and placement indicate they were almost certainly natural damage, caused by marine organisms before the shells were collected.

Choosing the Right Shell

One of the study’s more subtle insights concerns selection. The instruments that produce the best sound share a similar size—modified lengths between 140 and 191 mm. Before the apex was removed, they would have measured roughly 180–260 mm, a medium range for the species Charonia lampas. Larger shells existed, but were likely heavier and acoustically suboptimal. The consistency suggests that Neolithic craftspeople may have intentionally selected medium-sized shells precisely because they offered the best balance between portability and acoustic force.

Reconstructing a Lost Soundscape

By reviving the voices of these long-silent instruments, the study opens a window onto a soundscape that once bound communities together. Across Catalonia’s Neolithic world—between farmsteads, ritual sites, and the glittering green mines of Gavà—the resonant call of the triton shell may have carried warnings, instructions, or ceremonial signals.

It was a technology of distance, coordination, and identity at a time when societies were becoming more complex and spatially organised. These ancient trumpet blasts, echoing from valley to valley, may represent the earliest acoustic infrastructure ever established in the Iberian Peninsula.

And for the first time in millennia, thanks to modern archaeoacoustics, we can hear them again.

López-Garcia, M., & Díaz-Andreu, M. (2025). Signalling and music-making: interpreting the Neolithic shell trumpets of Catalonia (Spain). Antiquity, 99(408), 1480–1497. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.10220

Cover Image Credit: Neolithic shell trumpets from Catalonia. M. López-García, M. Díaz-Andreu, 2025