New genetic research from Uppsala University is reshaping our understanding of family, memory, and social bonds among Stone Age hunter-gatherers on the Baltic island of Gotland.

In a landmark archaeogenetic study at the Ajvide burial ground, scientists have reconstructed family relationships inside 5,500-year-old graves belonging to the Pitted Ware Culture (PWC), one of the last hunter-gatherer societies in northern Europe. The results show that burial arrangements were far from random: biological kinship played a decisive role, extending beyond parents and siblings to include cousins, aunts, and other close relatives.

The findings are detailed in the peer-reviewed study “Genetic relatedness mattered in the co-burial ritual of Neolithic hunter–gatherers,” published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

A Cemetery Unlike Any Other in Scandinavia

Ajvide, located on the western coast of Gotland, is one of the largest and best-preserved Stone Age burial grounds in northern Europe. Around 85 graves have been identified at the site, dating between roughly 3000 and 2500 BCE. Unlike farming communities spreading across much of Europe at the time, the people of Ajvide maintained a marine-based hunter-gatherer lifestyle, relying heavily on seal hunting and fishing.

While archaeologists have long studied grave goods, body positioning, and ritual patterns at Ajvide, this new research adds a genetic dimension. By sequencing DNA from ten newly analyzed individuals—primarily from double and triple burials—and combining them with previously published genomes from Gotland, researchers were able to examine kinship patterns with unprecedented resolution.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The results were striking.

Buried Together — Because They Were Family

In four co-burials examined in detail, every pair or group of individuals interred together turned out to be close genetic relatives—first-, second-, or third-degree kin.

One grave contained a 20-year-old woman laid on her back, flanked by two small children. DNA revealed that the children—a boy and a girl—were full siblings. But the woman was not their mother. Genetic evidence suggests she was likely their paternal aunt or possibly a half-sister.

In another burial, two children placed together were not siblings, but their DNA indicated a third-degree relationship—most plausibly cousins.

A separate grave revealed a father buried alongside his daughter.

In each case, mitochondrial DNA confirmed that maternal relationships could be ruled out when haplogroups differed, allowing researchers to narrow down possible family connections.

Importantly, statistical testing demonstrated that individuals buried together were significantly more genetically related than those buried separately elsewhere in the cemetery. This pattern strongly suggests that burial placement reflected conscious recognition of lineage.

As the researchers note, the co-burial ritual was closely associated with genetic relatedness, and family ties clearly mattered in mortuary decisions.

Children at the Center of Ritual Practice

One unexpected finding concerns children. Co-burials at Ajvide overwhelmingly included at least one subadult. Children were significantly overrepresented in shared graves compared to what would occur by chance.

This pattern hints at a deeper social logic. While some European Neolithic farming communities show evidence of patrilineal burial structures in monumental tombs, hunter-gatherer cemeteries rarely preserve enough individuals to reconstruct family networks.

Ajvide changes that.

The genetic results suggest that family memory extended beyond immediate parents and siblings. Even third-degree relatives—such as cousins or great-aunts—were intentionally buried together. That implies detailed knowledge of lineage across generations.

Interestingly, in at least one case, radiocarbon analysis suggests that individuals buried together did not necessarily die at the same time. This raises the possibility that later burials were intentionally arranged to maintain family proximity, reflecting collective remembrance rather than coincidence.

A Society Mostly Hunter-Gatherer — But Not Isolated

Beyond kinship, the study also explored broader ancestry patterns. Using population genetic modeling, researchers confirmed that the Pitted Ware Culture on Gotland derived roughly 80% of its ancestry from earlier Mesolithic Scandinavian hunter-gatherers, with approximately 20% originating from Neolithic farmer populations.

Notably, there was no evidence of gene flow from the contemporaneous Battle Axe Culture, despite cultural contact.

This genetic mixture reflects selective interaction rather than wholesale replacement. The Ajvide population maintained its hunter-gatherer identity while incorporating limited farmer ancestry over time.

Runs of homozygosity analysis also showed no strong signs of inbreeding. Although the effective population size was relatively small—expected for island hunter-gatherers—close-kin marriages appear to have been uncommon.

Rethinking Social Organization in Stone Age Europe

Kinship studies in prehistoric hunter-gatherer contexts are rare due to limited preservation of multi-burial sites. Ajvide provides an exceptional opportunity to examine internal social structure at scale.

The study suggests that biological family ties were a defining factor in burial organization. Yet, the relationships identified go beyond the nuclear family model. Extended kin—second- and third-degree relatives—were equally significant in mortuary practice.

This challenges older assumptions that early forager societies lacked structured lineage systems. Instead, the Ajvide evidence points to a socially complex community that tracked descent lines and maintained intergenerational connections.

The research team plans to expand their interdisciplinary investigation to more than 70 individuals from the cemetery, aiming to further illuminate social organization, migration patterns, and ritual behavior in one of Europe’s last hunter-gatherer cultures.

What the DNA Tells Us

The Ajvide findings offer more than just genealogical reconstruction. They reveal how ancient communities understood belonging.

Five and a half millennia ago, on a windswept Baltic island, families were not only living and hunting together—they were buried together, too. And through ancient DNA, those bonds are now visible again.

Tiina Maria Mattila, Magdalena Fraser, Julian Koelman, Maja Krzewińska, Marieke Ivarsson-Aalders, Anders Götherström, Mattias Jakobsson, Jan Storå, Torsten Günther, Paul Wallin, Helena Malmström; Genetic relatedness mattered in the co-burial ritual of Neolithic hunter–gatherers. Proc Biol Sci 1 February 2026; 293 (2065): 20250813. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2025.0813

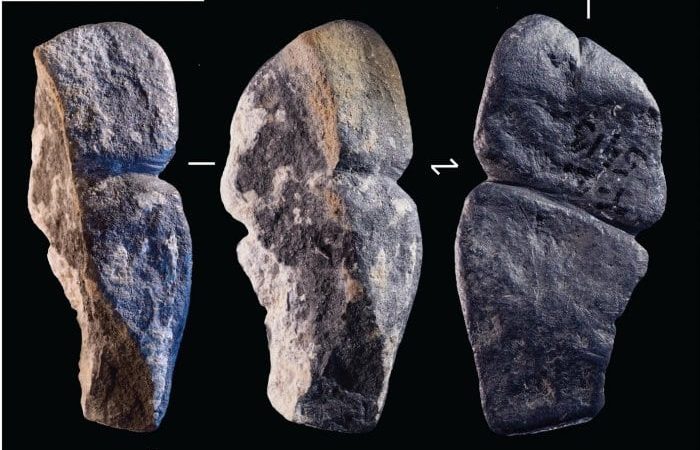

Cover Image Credit: In the fourth grave, there was a girl and a young woman. The analysis showed that they were third-degree relatives. Credit: Johan Norderäng – Uppsala University