Archaeologists in northern England have uncovered evidence of a previously unknown Roman military-industrial complex, revealing how the Roman Army prepared for war nearly 2,000 years ago.

On the banks of the River Wear near Sunderland, researchers supported by Durham University have discovered more than 800 Roman whetstones—essential tools used to sharpen swords, daggers, spears, and military equipment. Alongside them, 11 stone anchors point to a sophisticated river-based transport system designed to supply Roman forces across Britain and beyond.

Experts now believe the site at Offerton was not a minor workshop, but a strategic military production hub, operating on an industrial scale at the very edge of Rome’s northern frontier.

The Roman Soldier’s Most Essential Tool

In the Roman Army, sharp weapons meant survival. Every legionary carried a whetstone, ensuring blades remained battle-ready at all times. From infantry swords to agricultural tools used in military camps, whetstones were indispensable to Rome’s war machine.

Until recently, archaeologists had identified only around 250 Roman whetstones across the entire British Isles. The discovery of more than 800 examples at a single site therefore represents an unprecedented concentration of military-related equipment.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

According to Durham University archaeologists, the quantity, uniformity, and production waste found at Offerton strongly suggest mass production intended for military supply, rather than local civilian use.

Scientific Evidence Confirms Roman Military Activity

To confirm the age of the finds, researchers conducted Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) testing on sediment layers surrounding the artefacts. This method determines when mineral grains were last exposed to sunlight.

The results were decisive. Sediment beneath the whetstone layer dated to 42–184 AD, while the layer containing the whetstones dated to 104–238 AD—a period when Roman military presence in Britain was at its peak, including the construction and occupation of Hadrian’s Wall.

This places the Offerton site squarely within the operational timeline of Roman frontier defense.

A Factory Built for an Army

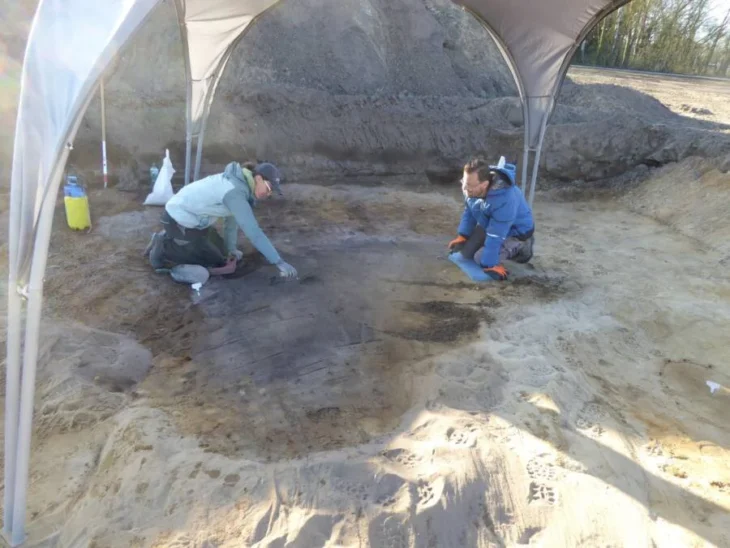

The whetstones recovered reveal every stage of production. Some remain rough and unfinished, bearing clear tool marks. Others show polished surfaces and carefully shaped edges, ready for deployment.

Archaeologists also identified 65 paired “double” whetstones, still joined before being split, and even a rare “treble”—strong indicators of standardized, high-volume output.

Crucially, every recovered whetstone is damaged. Researchers believe only flawed or broken stones were discarded on-site, while fully functional pieces were shipped out to military units. The Roman Army demanded strict uniformity, and substandard equipment was simply rejected.

Quarrying, Logistics, and River Transport

Evidence suggests sandstone was quarried deliberately on the northern bank of the River Wear and transported across the river for processing on the flatter southern side. This organized landscape strongly resembles known Roman military-industrial zones elsewhere in the empire.

The discovery of 11 stone anchors—the largest such concentration ever found in a northern European river— reinforces the idea of intensive logistics. These anchors were likely used by river vessels transporting heavy stone slabs and finished whetstones.

From the River Wear, supplies could be shipped to coastal depots and distributed by sea to Roman forts across Britain or even exported to the European mainland.

A Strategic Blind Spot Revealed

Perhaps most striking is what the discovery says about Sunderland’s role in Roman Britain. Despite lying close to Hadrian’s Wall, the region had previously yielded little evidence of Roman activity.

“This site puts Sunderland firmly on the Roman military map for the first time,” researchers note. “It shows that areas near the frontier were not empty buffer zones, but critical production centers supporting Rome’s army.”

Two Millennia of Conflict and Continuity

The military narrative of the site does not end with Rome. Excavations also uncovered later defensive and industrial features, including stone and wooden jetties, Tudor-era footwear, tools, and cannonballs from the English Civil Wars.

Together, these finds extend the history of conflict, logistics, and strategic use of the River Wear by more than 1,800 years.

Rewriting the Story of Roman Britain

Featured in the BBC series Digging for Britain, the Offerton discovery is already being described as one of the most important archaeological finds in northern England in the last century.

Above all, it reveals a hard truth of empire: Rome did not hold Britain through walls alone—but through factories, supply lines, and sharpened steel.

And on the banks of the River Wear, the Roman Army made sure its blades were always ready.

Cover Image Credit: A pair of double whetstones lying in the foreshore mud. Durham University