Researchers discovered that two anthropomorphic figures of indigenous warriors were created amid geopolitical tensions with the ruling class and other tribes in what is believed to be the first age study of Malaysian rock art.

New radiocarbon dating of rock art in the Gua Sireh cave complex is helping shed light on a tumultuous period for the Indigenous Bidayuh people of the Sarawak region, in what is now Malaysian Borneo.

Approximately 55 km southeast of Sarawak’s Capital, Kuching, the site is managed by the Bidayuh (local Indigenous peoples) in collaboration with The Sarawak Museum Department, with the drawings depicting Indigenous resistance to frontier violence in the 1600s and 1800s AD.

While the Bidayuh did not keep a written record of their history, they were among the Indigenous peoples who adorned the cave walls of Gua Sireh and elsewhere with rock art, using simple pigments to produce various motifs and drawings, depicting more than 300 images.

A team of Australian scientists recently used radiocarbon dating to complete the first chronometric age study of Malaysian rock art, as reported in an article published Wednesday in the journal PLOS One.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

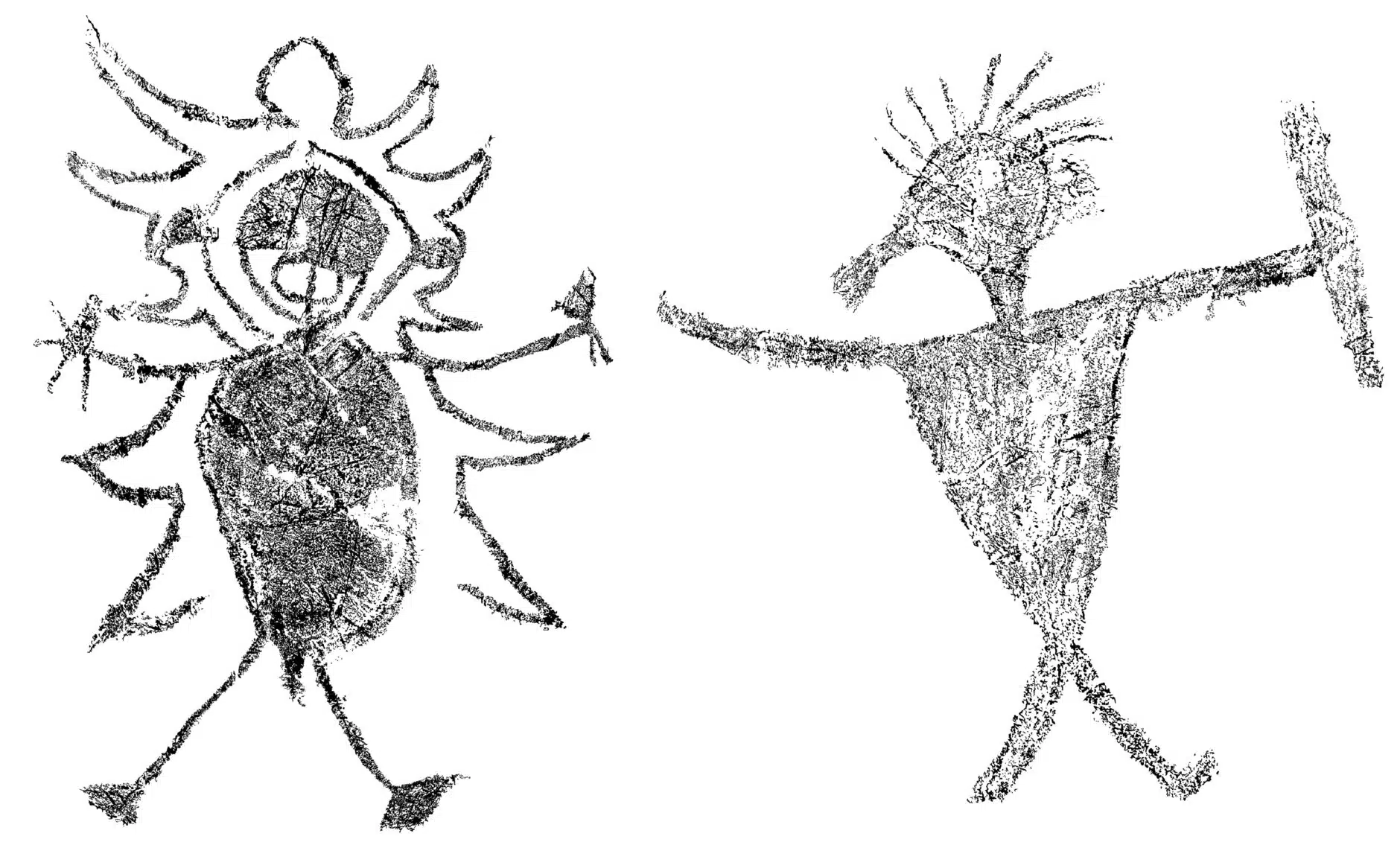

The team of researchers focused on the two largest charcoal drawings in the cave complex. One, identified as GS3, is a round-bodied human-like figure, with accoutrements including a cloak, headdress and knives in each hand. The other, GS4, is described as a large anthropomorphic figure with an infilled triangular body holding a sheathed knife.

New radiocarbon dating detailed in the article gives researchers a timeline for when the art was made: the GS3 figure was likely produced between 1670-1710 while the GS4 figure dates to 1800-1830.

These findings allow researchers to place the drawings in historical context.

“When the older anthropomorph was drawn, the Bidayuh were dominated by Malay elites, whereas the second large anthropomorph would have been made during a period of increasing conflict between Bidayuh and both Iban and Brunei Malay rulers,” the team said. “During this period many Indigenous Sarawakians moved into the upland interior, including the Gua Sireh area, to escape persecution.”

Though the two drawings are separated by as much as 160 years, they share characteristics including size, embellishment and possession of weaponry, indicating they were produced during periods of conflict.

GS3 has “a round body and is more embellished than most other anthropomorphs at the site with a large circular head, a mouth indicated and a defined penis, hands and feet. He also has an unusual outline with jagged edges around the body, five triangular shapes on either side of the body, and a rounded top above the head, giving the impression that it is wearing a cloak and/or headdress.”

Both drawings are surrounded by smaller human figures, suggesting they may represent “big and/or powerful warriors.”

The researchers’ work adds fresh details to the history of the region and its peoples.

“Black drawings in the region have been made for thousands of years,” study co-lead, Dr. Jillian Huntley said.

“Our work at Gua Sireh indicates this art form was used up to the recent past to record Indigenous peoples’ experiences of colonization and territorial violence.”

The researchers’ work adds fresh details to the history of the region and its peoples.

“The radiocarbon age determinations reported here sit neatly alongside other recently published numeric ages for the distinctive black drawings associated with the migration of Austronesian people across Southeast Asia,” the researchers wrote.

“In conjunction with detailed recording work and regional rock art analyses taking place, additional radiocarbon dating of black drawn rock art is poised to provide further insights into the Austronesian/Malay Diasporas, as well as the complexity of human history at Gua Sireh and broader Southeast Asia,” the authors said.

Although their ancestors’ presence on the northern side of the island can be traced back around 20,000 years and historical records indicate they often enjoyed autonomy, from the 17th through 19th centuries, the area was governed by the Brunei Sultanate, the Malay ruling class. Indigenous peoples, although considered allies, were often exploited and enslaved.

In simultaneous geopolitical conflicts with another Indigenous group known as the Iban, Bidayuh were occasionally tortured and killed over territory and resources.

Some published accounts detail turbulent centuries for the Bidayuh.

In her 1965 book “Sarawak,” photographer and historian Hedda Morrison recounted that “rulers not only bullied and enslaved the people but also had no compunction in allowing expeditions of the Ibans to attack … . [T]he Ibans kept the heads of the people they slaughtered and handed over the slaves they captured to the Brunei authority as their share of the loot.”

Another historical account written 102 years earlier by British Consul Spenser St. John describes a “very harsh” Malay chief who demanded possession of Bidayuh children. When they refused and the chief sent a 300-man force to exact revenge, the Bidayuh took up a defensive position in the Gua Sireh cave complex.

The conflict was only resolved after several days of Bidayuh resistance. The Malay chief never penetrated the cave entrance, instead retreating after killing two Bidayuh and taking another seven as prisoners.

The drawings of Gua Sireh have been studied before. During an archaeological excavation in 1959, the drawings were classified into four categories: “pinmen,” “birdmen,” “large” and “animals.” GS3 and GS4 were both classified as “large,” with one archaeologist describing GS3 as “supernatural in some way.”

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288902

Cover Photo: Digital tracings of the two large human figures dated in a radiocarbon study of rock art on the cave walls of Gua Sireh in Borneo. The figures are identified as GS3 (left) and GS4. Photo: Huntley et al., 2023, PLOS ONE, CC-BY 4.0 via Courthouse News Service