At the heart of Uşaklı Höyük (Uşaklı Mound), archaeologists have uncovered the “Lost Children’s Circle” — a mysterious Hittite-era ritual structure where the remains of seven infants lay hidden for over three millennia.

Uşaklı Höyük, a windswept mound on the Central Anatolian plateau, has long been a treasure trove for archaeologists. This summer, the 18th excavation campaign by the Italian Archaeological Mission in Central Anatolia revealed one of the site’s most haunting and enigmatic finds yet: the remains of infants, discovered in a context that may point to a ritual space from the Hittite era, over 3,000 years ago.

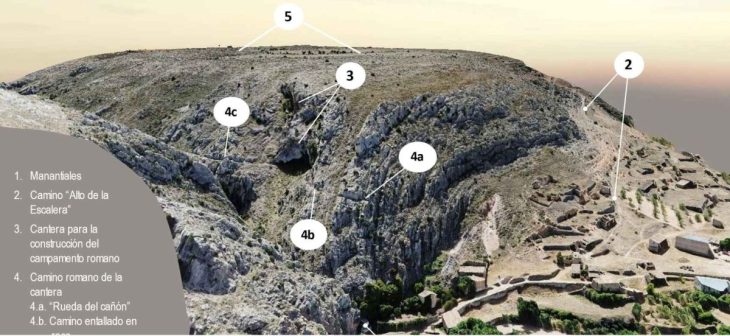

The 2025 season, led by researchers from the University of Pisa in collaboration with Turkish and international institutions, focused on three main areas of the site. Among these, the most intriguing work took place in Area F, home to the mysterious “Circular Structure” first uncovered in 2021. Previous seasons left archaeologists wondering about its function; the latest finds may finally offer some answers.

A Ritual Space in Stone

The Circular Structure, built of carefully laid stone blocks, sits on a terrace north of the citadel. New excavations revealed late Hittite-period walls that respected the structure’s boundaries, suggesting it retained its importance over centuries. Layers of stone pavements on its eastern side tell a story of repeated use.

But it was the soil above one such pavement that held the season’s most poignant discovery: a tiny tooth belonging to an infant. This was not the first such find—archaeologists have already uncovered a nearly complete skeleton of another infant, the remains of a newborn, and partial bones from at least four more perinatal individuals in the same area.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Unlike formal burials, these remains were found scattered or deposited alongside animal bones, ash, and fragments of ceramic vessels. Such arrangements hint at ritual practices, though the exact nature remains uncertain. Ancient Near Eastern societies often treated children’s remains differently from adults, sometimes placing them in homes or special areas rather than cemeteries. At Uşaklı Höyük, the connection between the infants and the monumental Circular Structure suggests a dedicated space for rites involving the youngest members of the community—whether as acts of mourning, dedication, or something more symbolic.

Unlocking Ancient Lives Through Science

The infant tooth could prove invaluable for science. Its excellent preservation means it may yield not only an exact radiocarbon date but also ancient DNA, offering rare biological insights into Hittite populations. The analysis will be carried out by specialists at the Human_G laboratory of Hacettepe University, whose results could reshape our understanding of the site’s ancient inhabitants.

These finds also feed into the ongoing debate over whether Uşaklı Höyük was in fact the ancient city of Zippalanda, a major Hittite religious center dedicated to the Storm God. References in cuneiform tablets describe temples, royal residences, and elaborate rituals—features that match the monumental buildings and ceremonial layout uncovered at the site.

A Settlement Through the Ages

While the infant remains captured headlines, the 2025 campaign also brought fresh insights into Uşaklı Höyük’s long history. On the citadel’s summit, archaeologists uncovered Iron Age to Hellenistic occupation layers, including paved courtyards, pillar bases, and a distinctive four-legged stone brazier. Notably absent were medieval layers, suggesting the summit was unsuitable for later habitation, unlike the lower city.

Excavations also revealed destruction layers from the Middle Iron Age, filled with burnt stones, ash, and pottery fragments—signs of a dramatic event in the site’s past. Charcoal samples from these contexts could soon refine the site’s chronology.

Specialist studies of animal bones, plant remains, and pottery are deepening the picture of daily life. From domesticated sheep, goats, and cattle to wild deer and boar, the faunal remains speak of a varied diet and a landscape that blended cultivated fields with wooded areas. Ceramic analysis is revealing what people cooked, stored, and served, offering a tactile connection to lives lived millennia ago.

Why Uşaklı Höyük Matters

First settled at the end of the Early Bronze Age, Uşaklı Höyük remained inhabited almost continuously until the Middle Ages. It occupies a strategic position in modern-day Yozgat province, along ancient routes that connected Central Anatolia with the wider Near East. Its monumental architecture, rich material culture, and tantalizing textual links to the Hittites make it a key site for understanding the political, religious, and social fabric of the ancient world.

The “Lost Children’s Circle” discovery adds a deeply human dimension to that story. It reminds us that archaeology is not only about palaces and kings, but also about the intimate, sometimes sorrowful, traces of everyday life—and death.

As scientific analysis continues, the team hopes to uncover not only the identities of these children but also the meaning behind their placement in such a prominent and enduring structure. For now, the Circular Structure stands as both a monument to Hittite engineering and a silent witness to rituals whose significance is only beginning to be understood.

Cover Image Credit: Uşaklı Höyük, the mound and part of the so-called terrace seen from the north (drone photo). Below, Area F with the Circular Structure is visible; at the top of the image, Area A with the large Building II can be recognized. On the summit of the citadel, along the southern edge, is the new excavation square. University of Pisa