Beneath the calm surface of Lake Bracciano, a submerged Neolithic village has preserved one of the most extraordinary collections of prehistoric wooden weapons ever discovered. At the site of La Marmotta, archaeologists have identified 19 intact wooden bows dating to the Early Neolithic—offering rare insight into archery technology, woodland management, and resource use among Europe’s first farming communities.

The new archaeobotanical study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, challenges long-standing assumptions about Neolithic bow-making. Instead of relying on yew—the wood traditionally considered ideal for bows—the inhabitants of La Marmotta crafted their weapons from a surprisingly diverse range of Mediterranean tree species.

The findings reshape our understanding of Neolithic hunting technology and demonstrate how early agricultural societies maintained a sophisticated relationship with forest ecosystems.

A Submerged Neolithic Village Frozen in Time

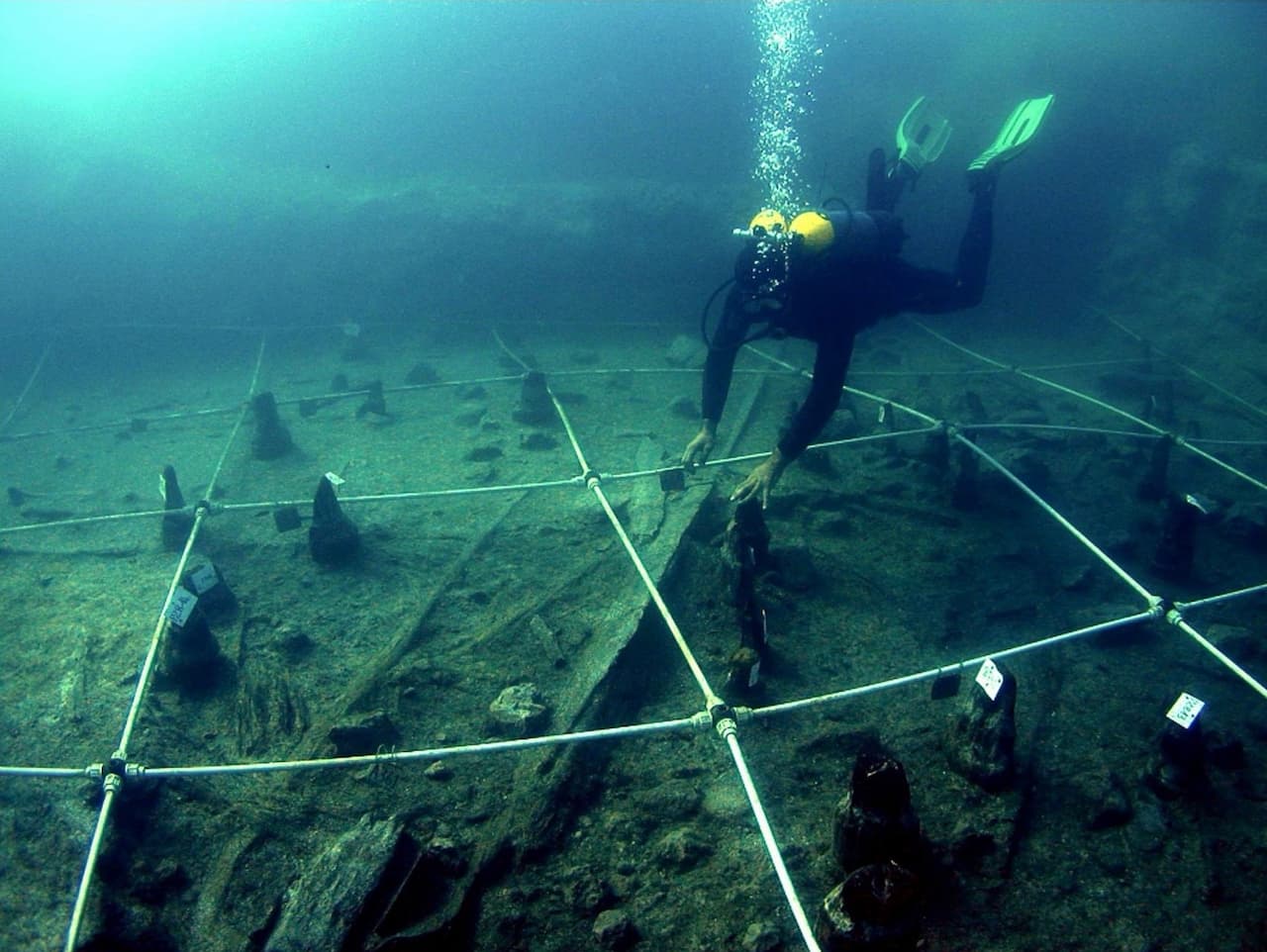

La Marmotta lies approximately 300 meters from the modern shoreline of Lake Bracciano, submerged at a depth of 11 meters. Occupied between roughly 5635 and 5230 BC, the settlement consisted of wooden houses built along the lakeshore. Over time, the village became submerged, and the combination of sediment cover and oxygen-poor conditions created an ideal environment for preserving organic materials.

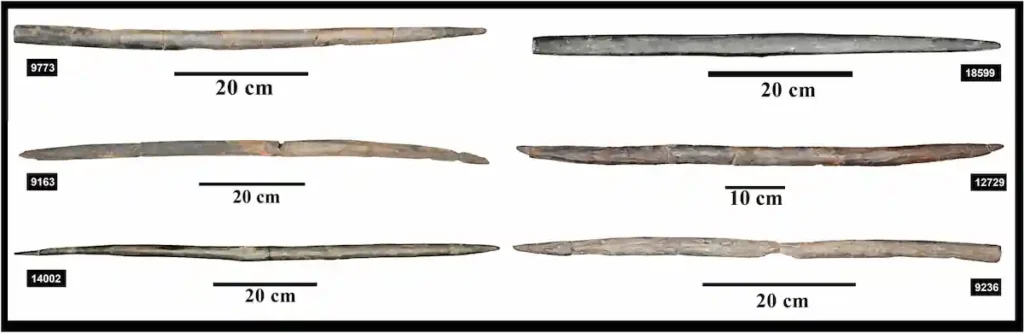

Wooden artifacts—normally lost to decay—survived in exceptional condition. Between 1993 and 2005, underwater excavations recovered at least 35 bows, along with paddles, canoes, stakes, and agricultural tools. The current study focuses on 19 of those bows, carefully sampled and analyzed to determine the species of wood used in their construction.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Complete Neolithic bows are exceedingly rare in Europe, typically found only in waterlogged or frozen environments. Sites in Switzerland, France, and Spain have yielded comparable examples, but La Marmotta stands out for the number and preservation quality of its finds.

Six Tree Species, One Technological Tradition

Microscopic anatomical analysis identified six different wood taxa among the 19 bows:

Carpinus sp. (hornbeam) – 9 examples

Viburnum lantana (wayfaring tree) – 6 examples

Alnus sp. (alder) – 1 example

Cornus sp. (dogwood) – 1 example

Fraxinus sp. (ash) – 1 example

Evergreen Quercus sp. (holm oak) – 1 example

This diversity is striking.

Across much of Neolithic Europe, bows were predominantly made from yew (Taxus baccata), prized for its unique mechanical properties. Yew combines compressive strength on the belly side of the bow with tensile flexibility on the back, allowing it to store and release significant energy during shooting.

At La Marmotta, however, yew is entirely absent.

Pollen data indicate that yew was not present in the surrounding environment during the Early Neolithic. Instead of importing preferred timber or abandoning archery traditions, the community adapted. They selected from the mixed Mediterranean forest available to them—demonstrating technological flexibility rather than rigid material preference.

Functional, Not Experimental

Were these bows practical weapons or merely symbolic objects?

Mechanical considerations suggest they were fully functional. Although none of the identified woods match yew’s optimal balance of stiffness and elasticity, all possess mechanical properties compatible with bow construction.

Hornbeam is dense and resistant to compression. Ash is known for its elasticity and shock resistance. Dogwood is both hard and flexible. Holm oak provides durability, while wayfaring tree offers straight growth suitable for shaping. Even alder, lighter and softer, can serve effectively in bow-making under appropriate design conditions.

In materials engineering terms, successful bow wood requires sufficient Modulus of Rupture (resistance to breaking) and appropriate Modulus of Elasticity (flexibility). The La Marmotta species fall within workable ranges. Experimental archaeology has previously demonstrated that many wood types—beyond yew—can produce effective self bows.

The Neolithic inhabitants of this lakeside settlement were not improvising blindly. They understood how to adapt design and craftsmanship to the material properties of each species.

Forest Management and Resource Strategy

Perhaps the most significant conclusion of the study is not technological, but ecological.

The taxonomic diversity observed in the bows mirrors patterns seen in other wooden artifacts from the settlement. The same tree species were used for house structures, paddles, dugout canoes, agricultural tools, and hunting equipment.

There is no evidence of strict, function-specific wood specialization. Instead, the data suggest a broad and opportunistic exploitation of available woodland resources.

This implies an intimate knowledge of the surrounding Mediterranean mixed forest ecosystem. The inhabitants of La Marmotta did not depend on a single “ideal” material. They worked with what their landscape provided, integrating hunting, construction, and farming within the same ecological framework.

Such adaptability would have been essential during a period marked by environmental fluctuations and the expansion of agricultural lifeways across Europe.

Hunting in an Agricultural World

Although Neolithic communities are typically associated with farming and animal domestication, the bows from La Marmotta confirm that hunting remained a significant activity.

Faunal remains from the site include deer, roe deer, wild boar, fox, and waterfowl. In addition, archaeologists recovered 546 geometric flint and obsidian arrowheads. Functional analysis of a sample showed that many display impact fractures consistent with projectile use, some even preserving traces of adhesive resins.

These findings demonstrate that archery was not symbolic or ceremonial—it was actively integrated into subsistence strategies.

The bow allowed hunters to strike prey at greater distances with improved accuracy, representing a major technological innovation in food procurement and possibly in defense or intergroup conflict.

Rethinking Neolithic Technology

The La Marmotta bows challenge the narrative of technological standardization centered on “optimal” materials. Instead, they reveal a flexible, context-driven approach to innovation.

Early farmers did not abandon woodland knowledge when they adopted agriculture. Rather, they maintained and adapted it. Archery technology at La Marmotta reflects continuity between foraging traditions and farming economies.

The community’s approach to wood acquisition appears consistent across tools and structures: select locally available resources, understand their properties, and adapt design accordingly.

In modern terms, this resembles sustainable resource management. There was no reliance on a rare or distant species. Diversity itself became a strategy of resilience.

A Window into Early Mediterranean Lifeways

The 7,500-year-old bows from La Marmotta provide rare direct evidence of Neolithic archery technology in the Mediterranean basin. More broadly, they illuminate how early agricultural societies balanced cultivation, hunting, and environmental knowledge.

Far from being technologically primitive, these communities demonstrated sophisticated material understanding and ecological awareness.

Under the waters of Lake Bracciano, preserved in silence for millennia, their wooden bows now tell a story of adaptation, ingenuity, and the enduring bond between humans and forest landscapes at the dawn of European farming.

Caruso Fermé L., Monteiro P., Brizzi V., Mineo M., Remolins G., Mazzucco N., Morell B., Gibaja J.F., Archery technology in the Neolithic: Management of the Mediterranean mixed forest and woodworking activities at La Marmotta (Italy). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 70, April 2026. doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2026.105609

Cover Image Credit: Excavation of the archaeological site of La Marmotta. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports april 2026