A barren desert today, the rocky landscape east of Aswan once served as the backdrop for one of history’s most groundbreaking political transformations. Over 5,000 years ago, in the deserts east of Aswan, an enigmatic figure carved his power into stone. Known to history as King Scorpion, he staged himself as a divine ruler while depicting violent imagery of conquest, laying the foundations for what scholars recognize as the world’s first territorial state.

Prof. Dr. Ludwig Morenz of the University of Bonn, together with Egyptian researcher Mohamed Abdelhay Abu Bakr, unveils the latest findings on these ancient rock carvings in their new book Culture and Power in Pre-Pharaonic Egypt: Visualizations of Rule in the Socio-Cultural Periphery of the Wadi el Malik and the Wadi Na’am during the Fourth Millennium BCE. Their research highlights how early Egyptian rulers used art, symbolism, and the landscape itself to legitimize authority.

King Scorpion and the Origins of Egyptian Kingship

Little is known about King Scorpion, but his legacy survives in stone. In a desert valley east of Aswan, researchers documented a rock inscription reading: “Domain of the Horus King Scorpion.” According to Morenz, this simple phrase is in fact the oldest known place-name label in the world—a groundbreaking marker in the history of writing and statehood.

“The Egyptian state emerged during this period as the first territorial state in world history,” says Morenz. By the late 4th millennium BCE, the kingdom already stretched nearly 800 kilometers along the Nile, linking diverse regions under a central authority.

King Scorpion was not alone in this political experiment, but his name—tied to one of nature’s most dangerous creatures—embodied authority, danger, and divine power.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

A Royal Tableau of Dangerous Beasts

The carvings do not depict Scorpion alone. Morenz calls the ensemble a “royal rock tableau”, featuring successive proto-dynastic kings identified by animals symbolizing authority. King Bull preceded Scorpion, while the sequence begins with King Horus-Falcon. Morenz recently identified a new figure, King Skolopender, named after the venomous centipede.

“The earliest royal names were often linked to dangerous animals, embodying strength and power,” Morenz explains. These symbols communicated authority and projected fear across the landscape.

Pharaoh-Fashioning and Divine Legitimacy

Central to Scorpion’s rule was “Pharaoh-fashioning”, Morenz’s term for the deliberate creation of a ruler’s divine persona. Scorpion’s kingship was associated with the goddess Bat, represented as a celestial cow, and the god Min, connected to hunting and fertility. Together, they represented the balance between fertile Nile lands and the surrounding desert, reinforcing the king’s role as mediator between natural and human worlds.

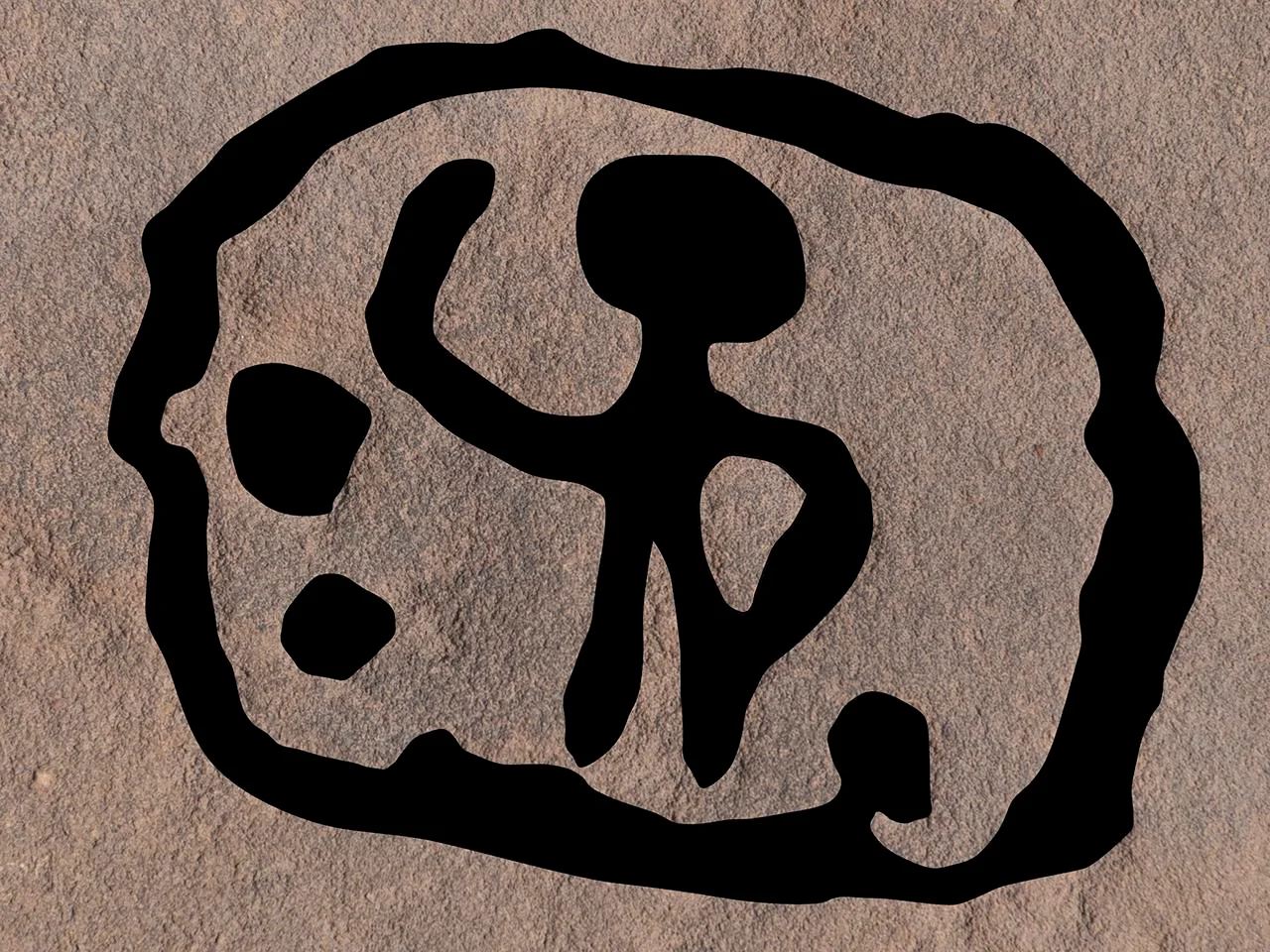

Violence and divine imagery were inseparable. Rock carvings depict rulers trampling enemies, decapitating captives, and towering over vanquished foes. “The most dramatic scene shows Scorpion crushing an enemy beneath his feet, with two severed heads behind him,” Morenz notes. These scenes visually reinforced the ruler’s invincibility and political ideology.

Ritual Boats and Sacred Landscapes

Alongside violence, the engravings also depict sacred rituals. One striking carving shows a “god’s boat” pulled by 25 men, symbolizing religious processions that connected distant desert valleys with the heart of the Nile civilization.

The choice of landscape was no coincidence. The Wadi el Malik, once a greener and resource-rich corridor, was both a practical route for expeditions and a symbolic stage for asserting control. What appears today as empty desert was once a contested arena where kingship itself was invented.

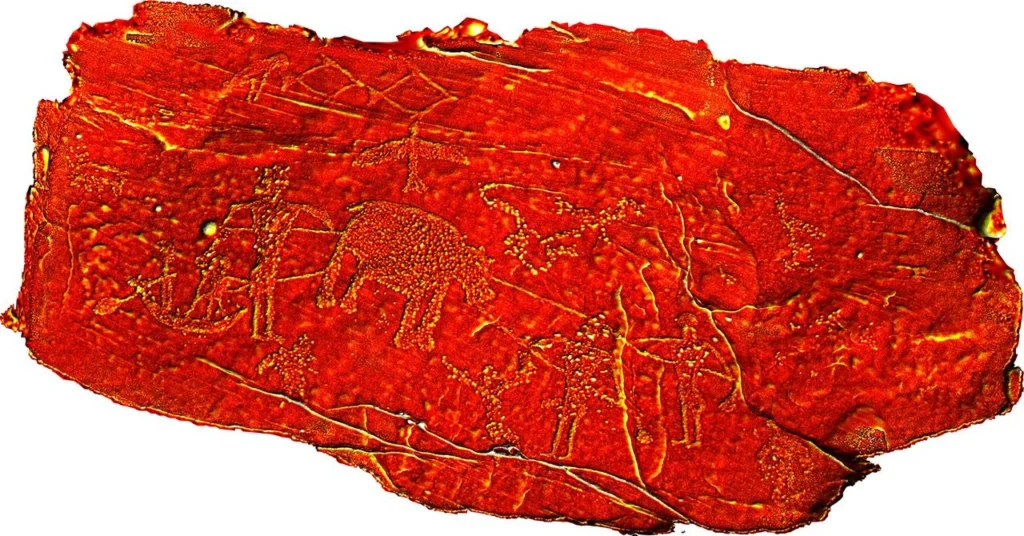

Digital Technology Unlocks Hidden Details

Morenz and his team applied advanced digital imaging methods, combining thousands of photographs taken from multiple angles to reveal subtle contours invisible in the field. These techniques have enabled researchers to document the rock art in unprecedented detail, uncovering the complex interplay of art, landscape, and power in pre-dynastic Egypt.

“The Wadi el Malik region is crucial for understanding early state formation in Egypt’s periphery,” Morenz explains. “We know much less about these borderlands than about central cultural hubs along the Nile.”

Toward Preservation and Public Access

Morenz emphasizes that rock art is not only about individual carvings but also their placement in the landscape, forming a total work of art. He hopes for a large-scale archaeological project and for the site to eventually be accessible to the public via guided tours and a visitor center, allowing people to experience firsthand where Egypt’s first kings established their authority.

King Scorpion’s Enduring Legacy

The story of King Scorpion demonstrates how violence, divinity, and symbolism intertwined to forge one of humanity’s earliest states. From scorpions to bulls and falcons, these carvings transformed a desert into a stage for power and ritual, linking geography, religion, and governance. Over 5,000 years later, the legacy of King Scorpion endures—etched into stone, revealing the birth of civilization itself.

Ludwig D. Morenz, Mohamed Abdelhay Abu Bakr: Kultur und Macht im vorpharaonischen Ägypten, Visualisierungen von Herrschaft in der sozio-kulturellen Peripherie des Wadi el Malik und des Wadi Na’am während des Vierten Jahrtausends (Culture and Power in Pre-Pharaonic Egypt, Visualizing Claims to Sovereignty in the Socio-Cultural Periphery of Wadi el Malik and Wadi Na’am during the Fourth Millennium), Katarakt, Assuaner Archäologische Arbeitspapiere 4, EB-Verlag, 244 pages, 39.80 euros. The book presents the findings in three languages: German, English, and Arabic.

Cover Image Credit: Martial scene of submission: The ruler crushes a man lying beneath him. The two round shapes behind him are not spheres, but severed heads. Credit: Johann Thiele