A routine restoration of the Karkoot Nag spring in the Salia area of Aishmuqam, Anantnag district, Jammu & Kashmir, has yielded a cache of ancient Hindu idols, including 11 intricately carved Shivlings.

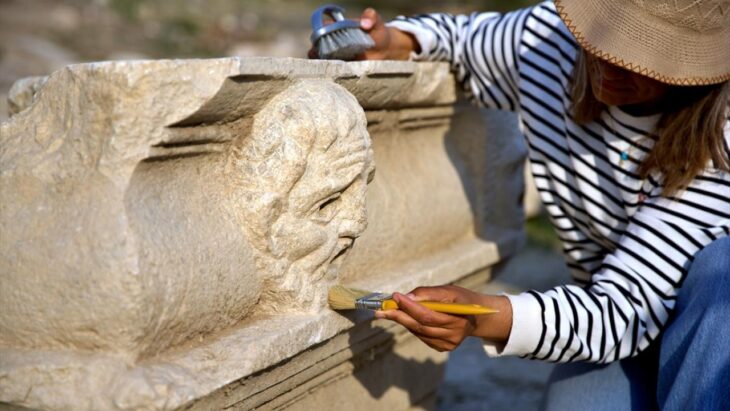

Unearthed by Public Works Department labourers, the find has swiftly been hailed as one of the most significant archaeological discoveries in the Valley in decades. Preliminary assessments by the Department of Archives, Archaeology & Museums (DAAM) suggest the stone artefacts date back to the Karkota dynasty (c. 625 – 855 CE)—a period revered for its flourishing temple architecture and scholarship.

As scholars rush to the Shri Pratap Singh (SPS) Museum in Srinagar to study the newly recovered treasures, locals are calling for the reconstruction of a shrine on the historic site.

What Is a Shivling?

Before delving deeper into the discovery, it is vital to understand the artefact at its heart—the Shivling (also written Shivalinga or Lingam). In Hinduism, a Shivling is a symbolic representation of Lord Shiva, one of the principal deities of the Trimurti (the trinity of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva).

Iconography: Typically crafted from stone, crystal or metal, the Shivling consists of a smooth, rounded pillar (linga) resting in a circular base (yoni). Together they symbolize the union of cosmic masculine and feminine energies, embodying creation, preservation and dissolution.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Ritual significance: Devotees pour water, milk, honey or ghee over the linga in daily worship known as abhishekam, invoking purification and divine blessings.

Historical reach: Archaeological records trace Shivling worship back more than 2,000 years; however, artistic depictions flourished during early medieval dynasties such as the Karkotas and later the Cholas, often featuring elaborate panchayatana (five-shrine) temple layouts.

Understanding the Shivling’s spiritual weight underscores why its discovery in situ—rather than in a museum display case—resonates so deeply with Kashmiri Pandits and wider Hindu communities.

Details of the Karkoot Nag Excavation

The spring restoration began under a government-funded heritage-revival programme aimed at reclaiming neglected water bodies across Jammu & Kashmir. While desilting the spring’s bed, labourers hit a stone slab that concealed 15 artefacts: 11 intact Shivlings, a partially broken temple-pillar sculpture and three deity panels thought to depict multi-armed forms of Shiva, Vishnu and possibly Shakti. Work halted immediately as DAAM officials secured the site.

Initial visual analysis indicates the idols were deliberately buried, likely to protect them during waves of conflict that swept the Valley between the tenth and fourteenth centuries. Carbon-dating and petrographic tests scheduled at the SPS Museum will refine their chronology and pinpoint the quarry sources of the stone.

Historical Context: The Karkota Dynasty

The Karkota rulers transformed Kashmir into a cosmopolitan hub of art and Tantra-inspired theology. King Lalitaditya Muktapida (r. c. 724–760 CE) erected monumental temples, including Martand Sun Temple, and promoted Sanskrit scholarship. The stylistic motifs on the newly found idols—fluted pedestals, lotus medallions and elongated jaṭāmukuṭa (matted-hair crowns)—mirror Karkota aesthetics, strengthening the hypothesis of an eighth-century origin.

Preservation and Community Response

All artefacts have been transferred to SPS Museum’s climate-controlled conservation wing, where curators will document, photograph and 3-D scan each piece. Once stabilized, the Shivlings will form the centrepiece of a new permanent gallery on Kashmir’s early medieval period. Local Kashmiri Pandit associations have petitioned the government to rebuild a modest temple near the spring, proposing that replicas—rather than the originals—be installed for worship to balance religious sentiment with heritage conservation.

Why the Discovery Matters

Academic value: The find offers rare, datable material to study regional variations in Shivling iconography.

Cultural reconnection: It rekindles interest among displaced Kashmiri Pandits eager to revive pilgrimage circuits.

Tourism potential: Coupled with Baramulla’s recent river-bed Shivling recovery, Anantnag could anchor a heritage trail linking multiple archaeological sites.

Conservation spotlight: The event underscores the importance of preventive archaeology during every infrastructure project in a heritage-rich landscape.

The unearthing of Shivlings and associated idols at Karkoot Nag spring is more than an archaeological headline; it is a bridge between Kashmir’s storied past and its contemporary quest for cultural revival.

As experts decode the stones’ secrets and policymakers weigh restoration proposals, the discovery stands as a timeless reminder of the Valley’s pluralistic legacy—one that, like the Shivling itself, unites creation and continuity in a single, enduring form.