In the mist-shrouded realms of ancient Turkic epics, there exists a race that haunts both myth and memory—the İtbaraks. These dog-headed, dark-skinned creatures are featured prominently in the Oghuz Khagan Narratives, representing the shadowy unknown, the mystical enemy, and the boundary between civilization and chaos.

Who Were the İtbaraks?

According to Turkic legends, the İtbaraks (or simply Baraks) were a mysterious tribe living in the northwestern frontiers, likely near present-day Siberia. The name itself combines two Turkic words: “İt”, meaning “dog,” and “Barak,” referring to a shaggy, long-haired breed of dog revered in ancient times. These beings were said to have the bodies of men but the heads of dogs, with black, devilish skin, and a nature both fearsome and enigmatic.

The text about İtbaraks in the Narratives: “Barak”, that’s what the Turks called the shaggy dog.

That’s how they named the big noble dog.

The Barak is told in the sagas.

It was believed to be other dogs ancestor.

This dog was noble, and enormously big.

Hunting and shepherd dogs was his sons.

In the Northwestern Asia, there was Itbarak.

Turks were far away from them in the Middle Asia.

They had body of a man, head of a dog.

Their color was dark, like the Black Devil.

Their women was pretty and didn’t run away from the Turks.

They were medicated, you couldn’t spear them.

The Battle Between Oghuz Khagan and the Itbaraks

According to the legends, Oghuz Khagan, the great Turkic ruler, once launched an ambitious campaign to conquer the lands of the Itbaraks. But the invasion failed. Defeated, Oghuz was forced to retreat with his remaining soldiers to a small, isolated island nestled between rugged mountains.

There, amid hardship and exile, a widow—possibly of Itbarak origin—gave birth to a child inside a hollow tree, as they had no home or tent. Oghuz named the child Kıpçak (or Kipchak), which in Old Turkic means “hollow.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Seventeen years later, Oghuz Khagan regrouped his forces and once again marched against the İtbaraks. This time, aided by the women who had once lived among them, he achieved victory. As a reward, he granted the conquered lands to Kıpçak, who would later become the ancestor of the Kipchak Turkic tribe—a powerful nation in Turkic history.

Interestingly, even within Turkic ancestry legends, creatures with animal-human hybrid forms appear. For example, the Tarduş Turks, a major part of the Eastern Göktürk state, claimed descent from a being with a wolf’s head and a human body.

The Dual Symbolism of the Dog in Turkic Mythology

To understand the myth of the İtbaraks, one must first explore how dogs were viewed in ancient Turkic belief systems.

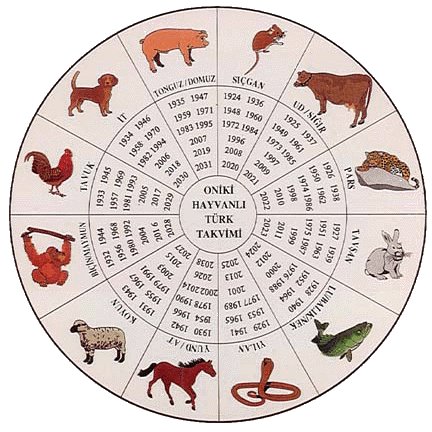

Contrary to modern misinterpretations, dogs held a sacred and multifaceted role in Turkic tradition. The 11th year of the ancient 12-animal Turkic calendar was dedicated to the dog, highlighting its spiritual importance. In shamanic culture, a specific breed—Barak, the shaggy long-haired dog—was believed to be a mount for shamans, helping them ascend to the heavens during rituals. Shamans often wore dog symbols and even mimicked barking to summon spirits or channel protective energies.

Dogs were also believed to guard the underworld and appear in dreams or trances as spiritual guides. In Altai creation myths, the god Ülgen assigned a dog to protect the first humans from his malevolent brother Erlik. Although the dog was eventually tricked, this tale emphasizes the dog’s loyalty and cosmic duty.

Furthermore, various Turkic and Central Asian tribes considered the dog a totemic ancestor. The Maymans revered a dog as their clan symbol; the Tatars traced their lineage to a red dog; and the Mongols believed they descended from a divine canine. In folk beliefs, especially among the Khazars and in Anatolia, dogs were thought to sense earthquakes—further affirming their mystical intuition and bond with nature.

The Itbaraks as the Mythical ‘Other’

In this rich cultural context, the İtbaraks emerge not as mere monsters but as symbolic representations of the foreign, the uncanny, and the feared unknown. While real dogs were sacred protectors, dog-headed beings represented a twist on the familiar, often associated with danger, otherness, or spiritual trial.

These beings are not exclusive to Turkic myth. Greek, Indian, and European mythologies also feature dog-headed humans. The Greeks spoke of Cynocephali, the Indians of divine canine guardians, and the medieval Europeans called them “Borus,” imagining them dwelling in northern Russia or Finland—geographically close to the Itbarak territories in Turkic lore.

Such similarities suggest a shared archetype across cultures: the dog-headed man as both fearsome and fascinating, monstrous yet mystical.

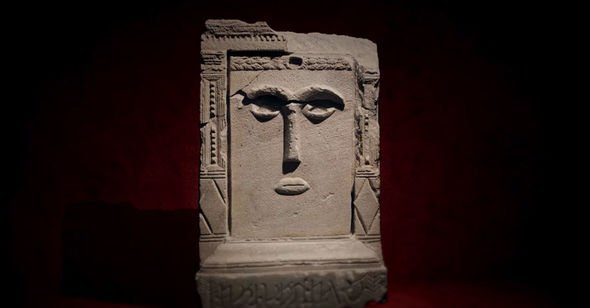

Intricate reliefs depicting the legendary It Barak (Cynocephaly) — the mythic dog-headed warriors of Turkic lore. Credit: Public Domain

Echoes of the Itbaraks in Collective Myth

The tale of the İtbaraks is more than a war story—it is a reflection of how ancient Turks defined themselves through myth, setting boundaries between the sacred and the profane, the self and the other, the loyal guardian and the monstrous hybrid.

By weaving these narratives through centuries of belief and storytelling, the Turks crafted a world where dogs could be holy guides, while dog-headed beings became the ultimate test of courage.

Bahaeddin Ögel, Turkic Mythology (Volume 1, Page 191-194

Hande Duymuş, F. H. (2014). Eski kültürlerde köpeğin algılanışı:“Eski Mezopotamya örneği”. Tarih Araştırmaları Dergisi, 33(55), 45-70.

Cover Image Credit: Image created with the assistance of Gemini AI technology.