Europe’s first toolmakers developed their own stone technology 42,000 years ago, according to a new study that challenges the idea that this early innovation was imported from the Near East.

A new study by researchers from the Universities of Tübingen and Arizona challenges the long-held belief that one of Europe’s earliest modern human cultures was imported from the Near East. Instead, Europe’s first toolmakers were technological pioneers in their own right.

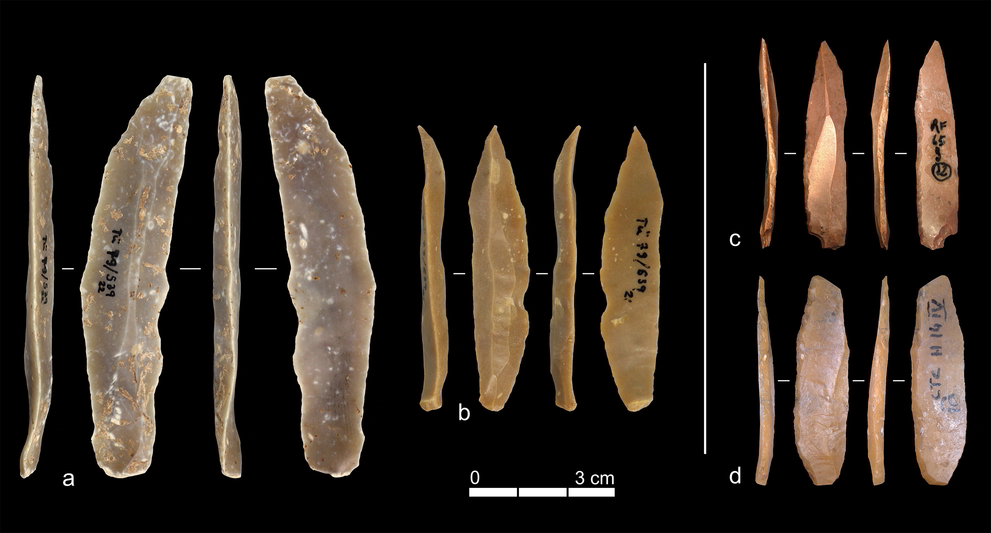

Archaeologists have long assumed that the Proto-Aurignacian culture, dated to around 42,000 years ago, arrived in Europe as part of a wave of modern humans migrating from the Levant. But a comparative analysis of thousands of stone tools from Italy and Lebanon suggests otherwise: the methods used to make these tools evolved independently in both regions.

Conducted by Dr. Armando Falcucci of the University of Tübingen and Prof. Steven L. Kuhn of the University of Arizona, the study—published in the Journal of Human Evolution—argues that early Europeans were innovators, not imitators, in the way they shaped and used stone.

Quantitative Evidence, Not Just Superficial Similarities

For decades, archaeologists linked the Proto-Aurignacian of southern Europe with the Ahmarian of the Near East because their tools looked alike—slender blades and bladelets produced from stone cores. Yet, no one had ever tested that similarity quantitatively.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Falcucci and Kuhn filled that gap. They compared lithic assemblages from Ksar Akil near Beirut, one of the key Ahmarian sites in the Levant, with material from Grotta di Fumane, Riparo Bombrini, and Grotta di Castelcivita in Italy—three of the oldest Proto-Aurignacian sites in Europe.

Using multivariate statistics, including multiple correspondence analysis of technological attributes, the researchers examined every stage of the tool-making process: how stone cores were shaped, how flakes and blades were detached, and how tools were retouched.

Their findings were unambiguous.

“Superficially, the tools look similar,” said Kuhn. “But the technological logic behind them is entirely different.”

While Ahmarian toolmakers in the Levant produced large blades through bidirectional core reduction, their European contemporaries focused on unidirectional production of small bladelets used in composite hunting weapons. Both groups miniaturized their tools over time, yet they did so through distinct technological paths.

Innovation, Not Import

The study concludes that Europe’s Proto-Aurignacian technology did not originate in the Near East, as previously assumed. Instead, independent innovation—driven by similar functional needs—better explains the pattern.

In both regions, toolmakers were developing complex projectile systems, reflecting the rise of mobility and precision hunting among early Homo sapiens. The researchers argue that such convergence should not automatically be seen as cultural transmission.

“The technological trajectories in the Levant and in Europe are distinct,” said Falcucci. “The data suggest that European forager groups developed their own projectile technologies rather than adopting them from Near Eastern migrants.”

This challenges diffusionist models that view Europe merely as the western endpoint of innovation flowing out of Africa and the Near East. Instead, the findings highlight a more multi-centered process of cultural evolution during the Upper Paleolithic.

Rethinking How Modern Humans Spread Across Eurasia

The Proto-Aurignacian period marks the dawn of modern human culture in Europe. Until now, scholars assumed that new technologies appeared in Europe through waves of migration from the Levant, a region long seen as the “biogeographical corridor” for human expansion out of Africa.

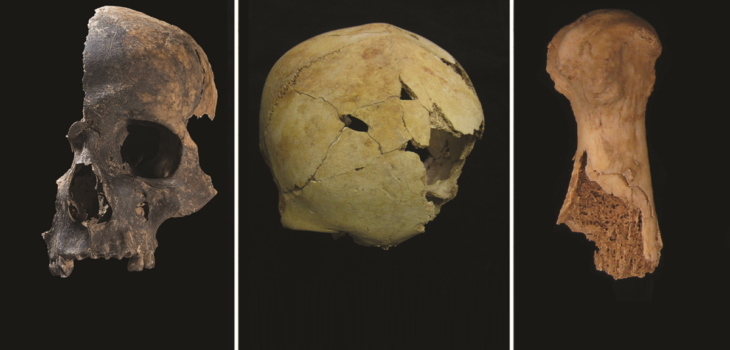

But growing fossil and genetic evidence shows that Homo sapiens had already begun spreading across Eurasia at least 60,000 years ago, interacting and interbreeding with Neanderthals and Denisovans. Against this background, Falcucci and Kuhn argue, technological similarities between regions should not automatically be equated with direct ancestry.

Their quantitative analysis supports the view that the emergence of early modern human culture in Europe was complex, non-linear, and regionally diversified.

“Our results reinforce the idea that cultural change cannot be reduced to migration alone,” said Falcucci. “Innovation and adaptation within local populations were equally powerful engines of progress.”

The Sites Behind the Discovery

Ksar Akil (Lebanon): A 22-meter-deep rockshelter sequence near Beirut preserving over 30 cultural layers spanning from the Middle Paleolithic to the Epipaleolithic. It yielded some of the earliest modern human fossils in the Levant, including “Egbert,” an eight-year-old Homo sapiens.

Grotta di Fumane (Verona, Italy): Contains Proto-Aurignacian levels dated between 41,200 and 40,400 years ago, rich in ornaments and bladelets.

Riparo Bombrini (Liguria, Italy): Dated to 40,700–35,600 years ago, showing intense tool production despite limited local raw materials.

Grotta di Castelcivita (Campania, Italy): Sealed by volcanic ash from the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption (39,850 ± 140 years ago), providing an excellent chronological anchor.

Across these sites, the researchers examined nearly 10,000 stone artifacts, including blades, cores, and retouched tools.

Broader Implications

By demonstrating that technological convergence can arise independently under similar ecological and functional pressures, the study adds nuance to our understanding of human prehistory.

It also strengthens the argument for viewing early modern humans not as passive carriers of a single “package” of cultural traits, but as active innovators capable of responding creatively to new environments.

“The assumption that Europe’s Paleolithic revolutions were simply imported from the Near East must be reevaluated,” said Kuhn. “Our study shows that innovation was happening in parallel across regions.”

Professor Dr. Karla Pollmann, Rector of the University of Tübingen, praised the work:

“Stone by stone, scientists are piecing together the story of our ancestors. It’s exciting to see Tübingen’s researchers continue to add new dimensions to that story.”

Falcucci, A., & Kuhn, S. L. (2025). Ex Oriente Lux? A quantitative comparison between northern Ahmarian and Protoaurignacian. Journal of Human Evolution. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2025.103744

Cover Image Credit: Examples of stone artifacts from the Ahmarian levels at Ksar Akil (a, b) and the Proto-Aurignacian layers at Grotta di Fumane (c) and Grotta di Castelcivita (d). Although the finished tools appear similar, Falcucci and Kuhn found that the technological methods used to produce them were markedly different. Panels a and b are from the lithic collection of the University of Tübingen; panel c is adapted from Falcucci et al. (2022), and panel d from Falcucci et al. (2024).