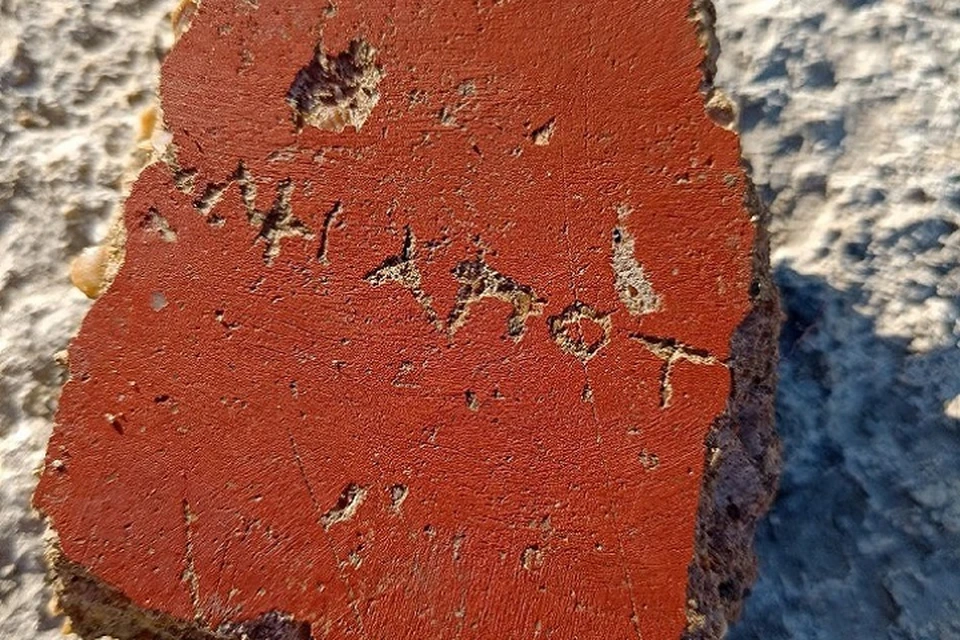

Archaeologists exploring the ancient settlement of Artezian in Crimea have uncovered a tantalizing piece of antiquity: a fragment of graffiti inscribed on temple plaster, hidden beneath a large slab in a pit east of the altar of the Zeus Genarcha temple. The find has stirred excitement in both archaeological and epigraphic circles, as the fragment may contain a short message that could shed light on local religious, social, or personal practices in the Bosporan realm.

The Artezian Settlement: Between Fortress and Sanctuary

Artezian (also spelled “Artesian” in some sources) lies in the Leninsky district of the Kerch peninsula, about five kilometers from the Sea of Azov. The site was more than just a minor outpost: it developed over centuries, from a Greek-influenced settlement into a fortified component of the Bosporan Kingdom, flourishing from the 6th century BC through late antiquity. Excavations began in 1988, and the total number of pits — sacrificial, ritual, or burial — investigated has already exceeded 860.

Artezian’s fortunes appear to have been closely tied to the vicissitudes of the Bosporan realm. According to recent studies, the settlement seems to have suffered a catastrophic destruction by fire during the mid-1st century AD, likely tied to the Roman-Bosporan war of 42–49 AD. Traces in the citadel show signs of conflagration, and some scholars suggest conflict between Roman forces and Bosporan factions loyal to the rebellious Mithridates III.

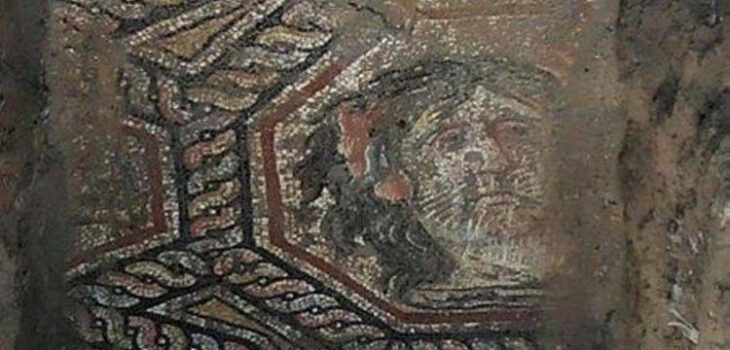

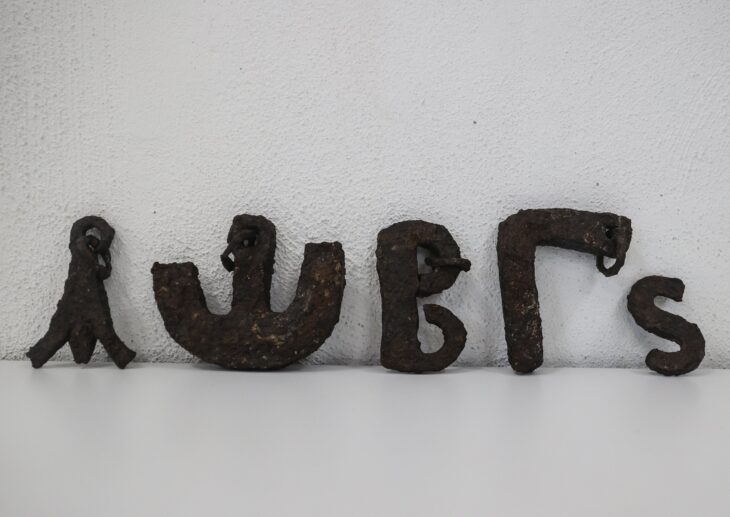

Past finds from Artezian include other epigraphic materials — in particular, a graffito presumed to be a school exercise that preserved a full Greek alphabet, a greeting formula, and a bawdy insult referencing a boy named Doles. The text also mentions Apatouros — a shared Bosporan sanctuary associated with Aphrodite. These finds suggest that Artezian’s population included Greek and Hellenized Bosporan elements, likely with a mixture of Thracian and Sarmatian background — a common pattern in the Bosporan colonies.

Against this backdrop, the newly found graffiti fragment takes on exceptional interest.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The Graffiti Fragment: Mystery in Four Letters

The archaeologists working at Artezian report that the fragment was found under a large stone slab, possibly hidden intentionally. The preserved letters (or their possible reconstructions) include ΜΝ ΑΡΓΟΤ / ΜN APOΤ / ΜΝ ΑΡTOT / ΜΝ ΑΡΙΟΤ — with ΜΝ ΑΡΓΟΤ seeming to be the leading candidate. The precise reading and meaning are not yet settled, and the task now lies with skilled epigraphists to determine whether this is a personal name, a dedication, an invocation, or something more cryptic.

If the inscription truly was hidden, it hints at deliberate concealment — which raises questions: was this a sacrificial or magical message, a warning or curse, or even an attempt to erase or hide something later? The brevity of the inscription challenges interpretation. It may reflect ritual shorthand, an abbreviation, or a colloquial local usage now lost to us.

Horse Sacrifice and Ritual Depositions

The graffiti find is not the only compelling discovery this season. Among a series of sacrificial pits linked to a high-status burial, archaeologists uncovered the dismembered remains of a young stallion. The lower legs were removed, and parts of the body were consumed — likely during a ritual banquet. The skull and bones up to the knee joints were arranged in an oval pit some 70 cm deep, then covered with ash.

Investigators propose that this partial sacrifice reflects a chthonic cult of decapitation — the ritual removal of the head symbolizing rebirth or regeneration. The orientation and arrangement of cranial fragments suggest a deliberate symbolic geometry, though the precise ritual logic remains opaque to researchers. The sacrifice may have accompanied the interment of a slain leader, perhaps to accompany or empower him in the afterlife.

Because of the complexity and unusual arrangement, scholars emphasize that while the symbolic logic is partly intelligible, many details — especially the spatial orientation of fragments — defy a clear ritual explanation.

Chronology and Context

Dating the graffito and ritual pits remains challenging. The working hypothesis places the events in early centuries AD or late antiquity, likely between the 1st and 3rd centuries. The destruction layer and the known dates of conflict at Artezian suggest that these rituals and graffiti may post-date the mid-1st century conflagration or perhaps belong to phases of reoccupation.

If the layered stratigraphy is intact, the graffito might be earlier than or contemporary with some of the sacrificial contexts — or else part of a later reuse of temple space.

Why the Find Matters

This new graffiti on temple plaster is rare: inscriptions on wall mortar or plaster in sanctuaries are seldom preserved, especially in contexts that suggest deliberate concealment. It grants a slightly more personal dimension to ancient religious life — someone scratched this message, perhaps hastily, perhaps with intent.

Combined with the ritual horse sacrifice and the broader funerary complex, the find contributes to a more textured view of beliefs, power displays, and ritual performance in the Bosporan periphery.

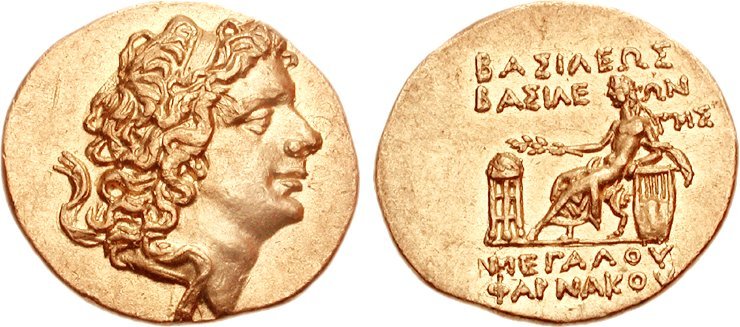

Pharnaces II: The King Who Left His Coins Behind

Among the many artifacts recovered at Bosporan sites, coins are among the most informative. One of the most evocative names from the Bosporan coinage tradition is Pharnaces II (reigned 63–47 BC) — a ruler of mixed Persian and Macedonian lineage who also held sway over the Bosporan Kingdom as a client monarch under Rome.

Pharnaces’ coinage is scarce and highly prized among numismatists. His gold staters remain extremely rare: in the 1970s, only about 15 were known; today, the total number of specimens in public and private holdings is estimated around 20–22. The obverse typically bears his diademed portrait; the reverse shows Apollo seated holding a laurel branch, often with a tripod, and bearing the legend ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΝ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΦΑΡΝΑΚΟΥ (“King of Kings Pharnaces the Great”).

Why mention him here? Because the presence (or absence) of coins like those of Pharnaces at Artezian can help archaeologists anchor phases of occupation, trade networks, and political allegiance. Finds of coins of Pharnaces or his successors help date strata, show monetary circulation, and hint at connections with the Bosporan capital and with Roman clients in the region.

Looking Ahead: What Epigraphists May Reveal

At present, the epigraphic puzzle is unresolved. Will the inscription turn out to be a name, a dedicatory abbreviation, a charm, or a ritual invocation? Its concealment suggests intentionality, which opens this fragment to a richer interpretive field — not just as an inscription, but as a communicative act in a ritual or political setting.

The combined discoveries — graffiti, ritual sacrifice, burial context — invite a holistic interpretation of spiritual life at Artezian. For scholars of the Black Sea’s ancient periphery, this is not a marginal find, but one that may recalibrate our understanding of how religion, writing, violence, and mortuary practices intersected in the Bosporan world.

Artezian Archaeological Expedition

Historical background information in this article is based in part on the study by A. Belousov, “The Site of Artesian in Eastern Crimea (Its Population and Cults),” Journal of Ancient History (VDI), No. 3, 2014, pp. 134–162 (in Russian, with English summary).

Cover Image Credit: Inscription on ancient temple plaster. Artezian Archaeological Expedition.