Archaeologists discover ancient human fossils and extinct megafauna on the seafloor of the Madura Strait, revealing that Homo erectus once thrived in a vast land now buried beneath the ocean.

An ancient world long swallowed by the sea has come back to light—along with clues about one of humanity’s earliest ancestors. Researchers have uncovered fossilized remains of Homo erectus, along with dozens of extinct animal species, from the bottom of the Madura Strait between Java and Madura islands in Indonesia.

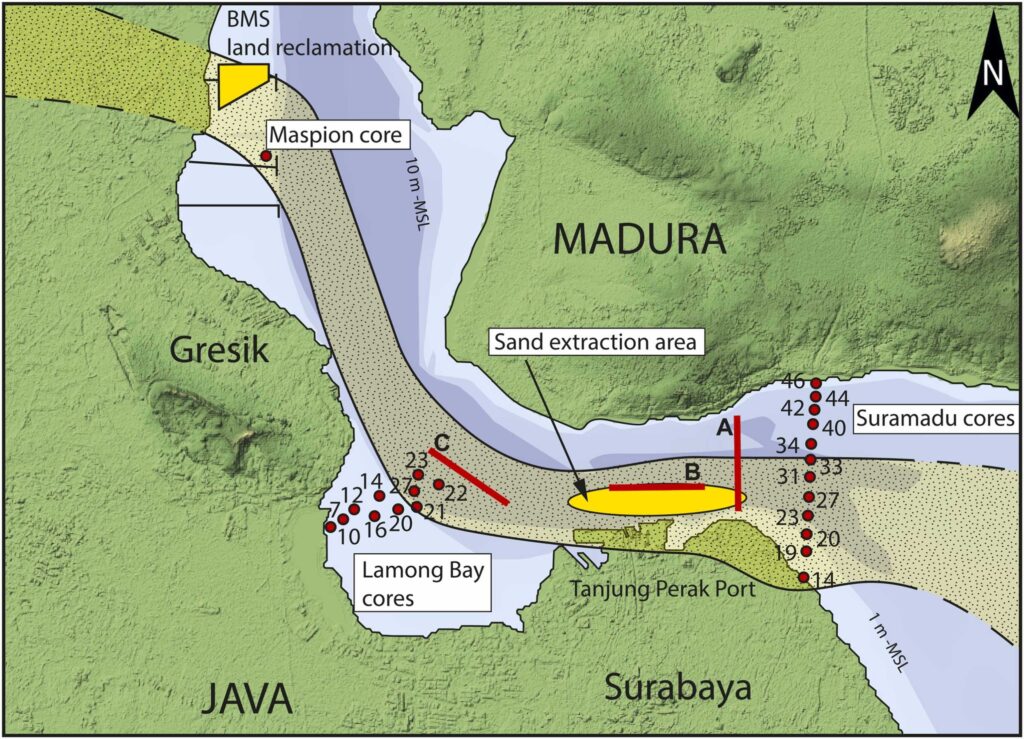

The fossils, dating back approximately 140,000 years, were discovered during dredging operations and include two Homo erectus skull fragments, bones with cut marks from butchering tools, and evidence of deliberate hunting behavior. The find sheds new light on early human life in Sundaland, a now-submerged landmass that once connected much of Southeast Asia.

“This discovery paints a vivid picture of a thriving ecosystem and an intelligent, adaptive Homo erectus population,” said Dr. Harold Berghuis, lead archaeologist from Leiden University.

A Sunken Land of Life and Intelligence

During the last Ice Age, global sea levels dropped by over 100 meters, exposing vast lowlands. What is now ocean between Indonesia’s islands was once a savannah-like region filled with elephants, rhinos, crocodiles, river sharks, Komodo dragons, and early humans.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The excavation site—a buried river valley now beneath the sea—has preserved this ecosystem remarkably well. Archaeologists recovered remains from 36 different vertebrate species, many of which are now extinct or endangered. Among them: The Asian hippo (extinct), Early forms of Komodo dragons, Ancient bovids and elephants, Carnivores and scavengers, likely hunted by Homo erectus.

“This was not a barren or remote outpost,” Berghuis explained. “It was a lush, resource-rich environment where early humans thrived.”

Homo Erectus Was Not Isolated—They Adapted and Hunted Strategically

Previously, many scientists believed that Homo erectus lived in isolation on Java, cut off from the rest of the Asian continent. But these new findings challenge that view.

The presence of butchered animal bones and shellfish remains suggest that Sundaland Homo erectus actively hunted, fished, and processed food in sophisticated ways. The cut marks on turtle shells and cracked bovid bones point to organized hunting and marrow extraction, behaviors typically associated with more modern hominins.

Some researchers even propose that Homo erectus in Sundaland may have interacted—or interbred—with other hominin species from mainland Asia.

“We see behaviors here that weren’t previously linked to early Java hominins. It may suggest some level of contact or cultural borrowing,” said Berghuis.

A Fossil Trove Heads to the Museum

The fossils are currently housed in the Geological Museum in Bandung, Indonesia. Plans are underway for a public exhibition to showcase the discovery, with possible traveling displays to other institutions around the world.

The full research findings were published in the journal Quaternary Environments and Humans, co-authored by experts from the Netherlands, Indonesia, Australia, Germany, and Japan.

Why It Matters: Rewriting Southeast Asia’s Human History

This discovery is reshaping how scientists view the prehistoric world of Southeast Asia. For decades, the narrative surrounding Homo erectus in this region was one of relative isolation—an early human species confined to the island of Java, evolving independently and cut off from the broader currents of human development across mainland Asia. But the fossil evidence retrieved from the seabed tells a far more dynamic and interconnected story.

These remains suggest that Homo erectus was not a static, isolated population, but rather a geographically mobile and ecologically adaptable species. The presence of butchered animal bones and evidence of strategic hunting indicates not only intelligence and survival skills but a capacity for behavioral complexity far beyond previous assumptions. They were exploiting a rich and diverse environment, adjusting to changing landscapes and possibly interacting with other hominin groups—either through contact, cultural exchange, or even interbreeding.

Moreover, this discovery opens a previously invisible chapter in both the biodiversity and cultural history of the region. The now-submerged land of Sundaland was once a thriving habitat—comparable to the African savannah—home to large mammals, river systems, and early human life. That it now lies underwater underscores how much of our shared human story may still be concealed beneath rising seas.

“This is just the beginning,” says Dr. Berghuis. “We are likely standing at the edge of an enormous, underwater archaeological archive. There’s so much more to discover—entire landscapes, ecosystems, and lifeways that time and tide have hidden for millennia.”

Berghuis, H. W. K., Veldkamp, A., Adhityatama, S., Reimann, T., Versendaal, A., Kurniawan, I., Pop, E., van Kolfschoten, T., & Joordens, J. C. A. (2024). Fossil vertebrates and Homo erectus from the Madura Strait, Indonesia: A unique window on Sundaland 140,000 years ago. Quaternary Environments and Humans. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qeh.2024.100073

Cover Image Credit: Leiden University