A large-scale archaeological excavation carried out by the Israel Antiquities Authority has revealed a striking glimpse into how Jerusalem was built during one of the most formative periods of its history. In the Ramat Shlomo neighborhood of Jerusalem, archaeologists uncovered a massive stone quarry dating to the 1st century CE—at the height of the Second Temple period—alongside a rare curved metal key that may have belonged to one of the quarry workers themselves.

The excavation was conducted in 2007 ahead of modern development and directed by archaeologist Irina Zilberbod. Although the site has been known to specialists for some time, the Israel Antiquities Authority recently highlighted the discovery in a public statement, drawing renewed attention to the scale and sophistication of Jerusalem’s ancient construction industry.

A Quarry That Built a City

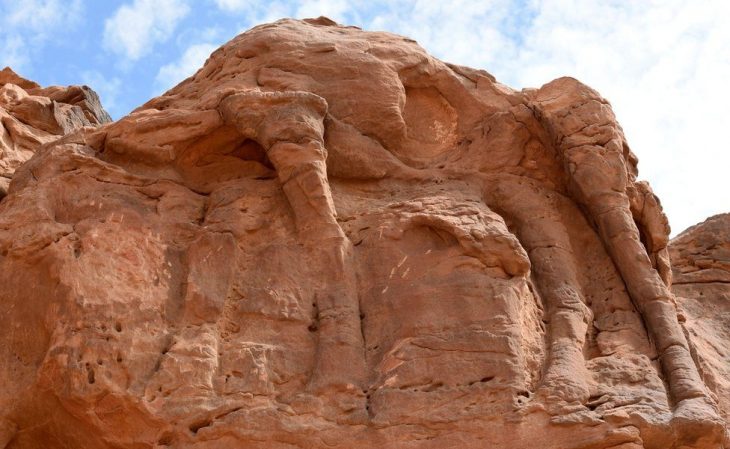

The quarry, carved directly into Jerusalem’s bedrock, preserves clear evidence of intensive and organized stone extraction. Archaeologists documented large depressions created by quarrying, standing rock pillars left behind during extraction, rock-cut steps, and stone blocks frozen in different stages of production. Some blocks were still attached to the bedrock, while others had already been shaped and partially detached.

Several of the quarried stones exceeded two meters in length, suggesting they were intended for monumental public architecture. Such blocks are characteristic of the large ashlar stones used in Jerusalem’s major Second Temple–period projects, including city fortifications, public buildings, and monumental streets. Their size and precision reflect both advanced technical knowledge and the enormous demand for building materials in a rapidly expanding city.

Tools of the Trade—and a Personal Object

Among the most evocative finds were iron quarrying tools used by the stonecutters. These included axes designed to carve detachment channels around stone blocks and a splitting wedge used to separate the stone from the bedrock with controlled hammer blows. Together, they provide rare physical evidence for the methods described in ancient sources but seldom preserved archaeologically.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Even more personal was the discovery of a curved metal key with protrusions, known as a crank key. Such keys were used to operate wooden locking mechanisms common in the Roman period. Archaeologists suggest it may have slipped from the pocket of a quarry worker during the workday, offering a rare human-scale moment within an industrial landscape.

Engineering Beyond Stone Cutting

The quarry was not merely a place of extraction. Researchers identified rock-cut auxiliary installations, likely used to collect and store water essential for quarrying activities. In addition, more than 200 small hollows were carved systematically into the quarry floor. Their regular layout indicates they were probably sockets for wooden beams, which would have supported lifting devices used to raise and move heavy stone blocks.

This infrastructure points to a highly organized operation, one capable of producing standardized building materials efficiently. The evidence reinforces the idea that stone quarrying in Second Temple Jerusalem was not an ad hoc activity but part of a city-wide construction economy.

Jerusalem in the Second Temple Period

The Second Temple period, roughly spanning from the late 6th century BCE until the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE, was marked by dramatic urban growth. Under Hasmonean and later Herodian rule, Jerusalem was transformed into a monumental city of stone. Herod the Great, in particular, initiated vast construction programs, including the expansion of the Temple Mount using enormous limestone blocks—some weighing several tons.

Quarries like the one at Ramat Shlomo were essential to this transformation. Local limestone, known as meleke, was prized for its durability and ability to harden after exposure to air. The proximity of quarries to the city reduced transport distances, though moving multi-ton stones through Jerusalem’s rugged terrain remained a formidable challenge.

Layers of Continued Use

The site also yielded finds from later periods, indicating that the quarry or its surroundings continued to see activity long after the Second Temple era. Archaeologists recovered a small number of Early Roman jar fragments, three coins dating to the time of the Roman prefects in Judea, and a lamp fragment bearing an inscription from the Late Byzantine period. A bone tool found at the site adds to this picture of intermittent reuse.

From the modern era, 17 metal horseshoes were discovered, some still retaining their nails—clear evidence that the area remained accessible and in use well into recent centuries.

Quarrying or Transporting—Which Was Harder?

The Israel Antiquities Authority posed a simple but telling question alongside its announcement: what was more difficult—quarrying the stones, or transporting them? The finds from Ramat Shlomo suggest the answer may be both. While the quarry workers mastered the art of cutting and shaping massive blocks, the logistical challenge of moving them into the heart of ancient Jerusalem was no less impressive.

Together, theamat Shlomo’s quarry and its modest lost key illuminate the immense human effort behind Jerusalem’s stone-built grandeur, reminding us that the city’s monumental past was shaped not only by kings and priests, but also by skilled laborers whose work still lies beneath the modern city.

Cover Image Credit: Zila Shagiv and Clara Amit, Israel Antiquities Authority