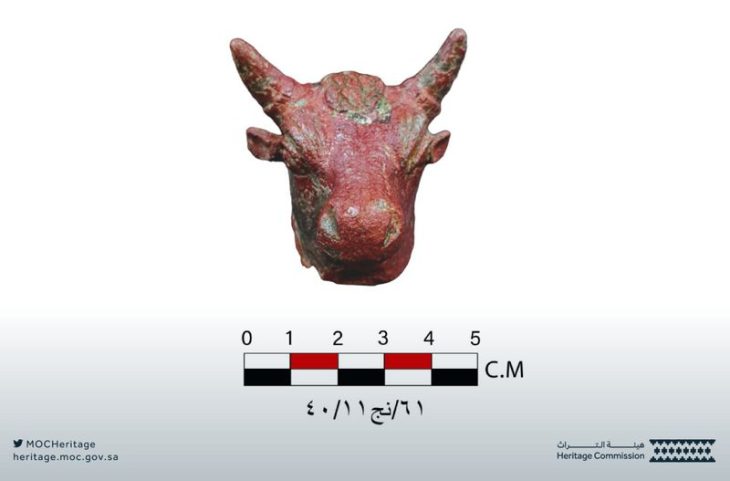

A small silver vessel discovered more than half a century ago in the Judean Hills has once again become the center of debate among archaeologists. Known as the ʿAin Samiya Goblet, the 8-centimeter-tall cup dates to the Intermediate Bronze Age (ca. 2650–1950 BCE) and is decorated with one of the most intricate mythological scenes ever found from this period in the southern Levant.

In a newly published study, geologist-turned-geoarchaeologist Eberhard Zangger and his colleagues argue that the goblet does not depict a specific myth such as the Babylonian Enuma Elish, as long believed. Instead, they suggest it represents a far older and more universal idea: the creation of cosmic order from primordial chaos.

The claim has reignited long-standing discussions around the object — and around Zangger himself, a researcher whose earlier theories, including high-profile claims linking Bronze Age cultures to Atlantis, have drawn sharp criticism from many specialists.

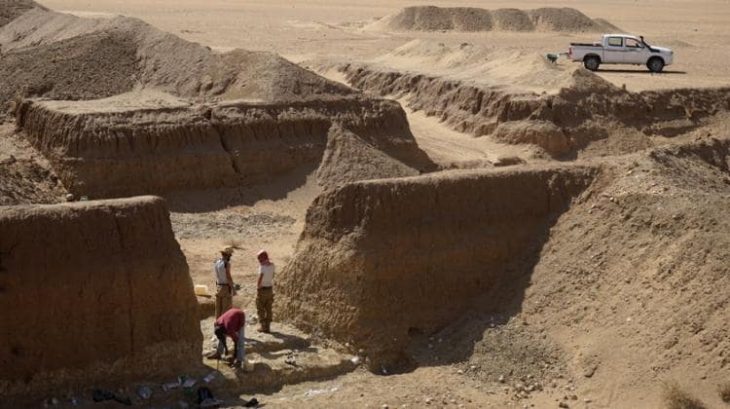

A Unique Object from a Modest Grave

The goblet was uncovered in 1970 in a high-status tomb near the spring of ʿAin Samiya, east of Ramallah. Although the burial itself contained mostly ordinary pottery and weapons, the silver cup stood out immediately. To this day, it remains the only known luxury silver vessel from this period ever found in the southern Levant.

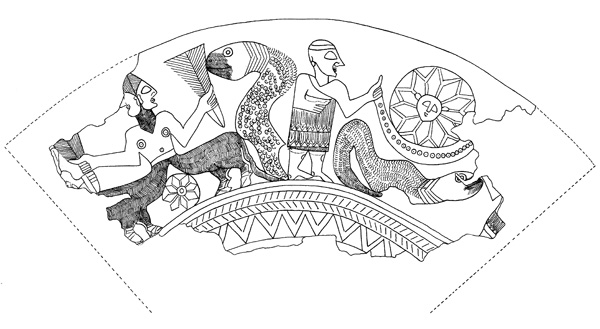

Its outer surface is decorated with two complex scenes arranged side by side. Hybrid creatures, serpents, plants, and celestial symbols are rendered in repoussé relief, forming a dense narrative that has puzzled scholars for decades. Early interpretations linked the imagery to the Mesopotamian creation epic Enuma Elish, which describes the god Marduk defeating the chaos monster Tiamat.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

However, the goblet predates the written version of that myth by nearly a thousand years.

Chaos, Order, and the Rising Sun

Zangger and his team propose a different reading. According to their analysis, the two scenes illustrate successive stages of creation rather than a violent divine battle.

In one scene, a chimera-like being — part human, part bull — appears alongside an upright serpent and stylized plant forms. The figures seem fused and unstable, symbolizing a world before proper separation: before animals, humans, plants, and even genders had distinct roles.

In the second scene, two human figures lift a crescent-shaped object containing a radiant sun disk. Beneath it, the serpent appears subdued, lying horizontally rather than rearing upright. The researchers interpret the crescent as a “celestial boat,” a motif known across the ancient Near East that carried the sun and moon through the sky.

Together, the scenes are read as a visual narrative of cosmic organization — the transition from chaos to a structured universe governed by cyclical renewal.

Influences Beyond the Levant

The study argues that while the goblet was buried in the Judean Hills, its artistic and symbolic roots lie elsewhere. Comparative analysis suggests that the iconography draws heavily on Mesopotamian traditions, with parallels in Sumerian, Akkadian, Egyptian, and even Anatolian cosmology.

Zangger’s team proposes that the design was conceived by a southern Mesopotamian artist, while the object itself may have been crafted in northern Syria, where access to silver was easier. From there, the goblet could have traveled south along established trade routes before eventually being deposited in the tomb.

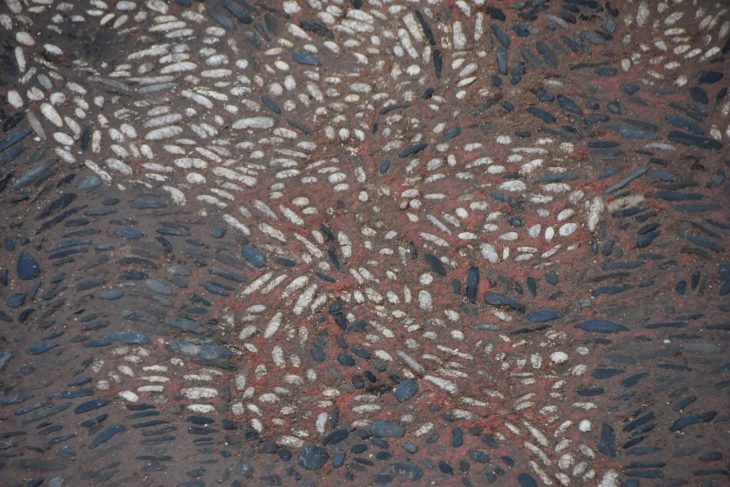

To support their argument, the researchers point to a little-known limestone prism from Lidar Höyük in southeastern Türkiye, decorated with similar celestial imagery. Though far cruder in execution, the prism suggests that such cosmological symbols circulated widely long before classical mythological texts were written.

Scholarly Caution Remains

Despite the study’s detailed iconographic comparisons, many scholars urge restraint. Zangger’s past work has often been criticized for drawing far-reaching conclusions from limited evidence, and some experts argue that the goblet’s imagery remains too ambiguous to support a single overarching interpretation.

Critics also note unresolved issues surrounding the goblet’s restoration history and the fragmentary state of the object, which complicate efforts to reconstruct the full narrative.

Still, even skeptics agree on one point: the ʿAin Samiya Goblet represents an extraordinarily early attempt to visualize humanity’s place in the cosmos.

Whether it depicts the birth of the universe, a funerary vision of rebirth, or a broader Near Eastern cosmological worldview, the tiny silver cup continues to punch far above its weight — reminding researchers just how much of the ancient imagination remains open to interpretation.

Zangger, E., Sarlo, D., & Haas Dantes, F. (2025). The earliest cosmological depictions: Reconsidering the imagery on the ʿAin Samiya goblet. Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society “Ex Oriente Lux”, 49–66.

Cover Image Credit: Public Domain – Wikipedia Commons