A 2,000-year-old Roman inkwell found in Conimbriga reveals an advanced mixed-ink formula, challenging what we know about ancient writing technology and Roman innovation.

The rediscovery of a modest bronze cylinder in Conimbriga, one of Portugal’s best-preserved Roman cities, has turned into one of the most significant breakthroughs in the study of ancient writing. What initially appeared to be a routine inkwell has revealed something far more consequential: microscopic traces of a sophisticated, multi-ingredient ink that upends long-held assumptions about how Romans wrote, produced pigments, and shared technological knowledge across the Empire.

Archaeologists and chemists working together have now demonstrated that the tiny object—classified as a Biebrich-type inkwell from the early 1st century CE—contained an unusually complex “mixed ink,” combining soot, bone black, iron-gall components, wax, and animal-based binders. For a province situated at the far western edge of Roman rule, this level of technical refinement is unexpectedly advanced. And it forces a re-evaluation of how quickly specialist knowledge moved between major administrative centers, frontier zones, and provincial towns.

A Humble Tool with Imperial Reach

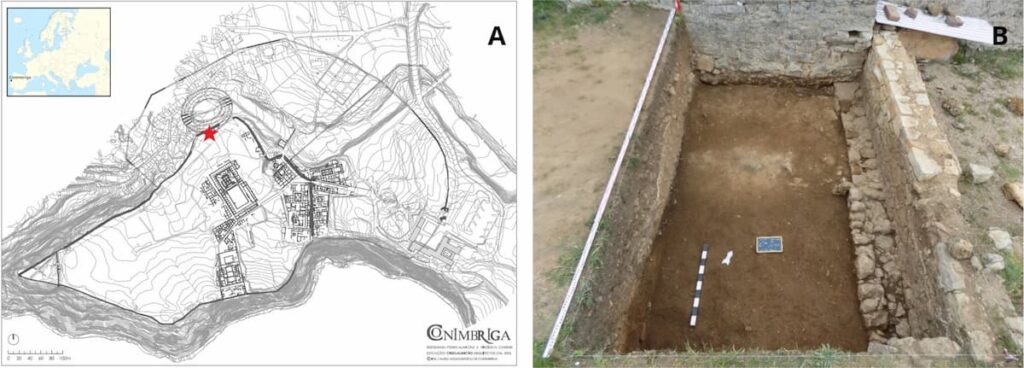

The inkwell emerged from construction layers related to Conimbriga’s late Roman fortification wall—specifically from deposits associated with the demolition of the city’s amphitheater. The stratigraphy suggests the object slipped from a bag or case during large-scale public works, likely belonging to someone whose daily responsibilities included writing: an architect, surveyor, military scribe, or municipal administrator.

Typological study, however, points to an earlier origin. Biebrich-type inkwells are typically dated to the first half of the 1st century CE and are most common in northern Italy and along the Rhine frontier, where they appear in military and engineering contexts. Their presence so far west in Lusitania indicates that mobility—of tools, of people, of knowledge—was more dynamic than previously assumed.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

At 94.3 grams, the inkwell is made from a bronze alloy of copper, tin, and a strikingly high percentage of lead. The lead improved molten metal fluidity, enabling the thin, regular walls and sharply defined lathe-cut grooves visible on the vessel’s exterior. This technical precision places the piece among the higher-quality writing instruments of the period.

The Ink That Should Not Have Survived—But Did

Finding a Roman inkwell with preserved ink residues is exceptionally rare. Most ancient inks were water-soluble or degraded quickly due to humidity. Yet Conimbriga’s inkwell protected a compact layer of pigment sealed inside for nearly two millennia.

The research team applied a suite of high-resolution techniques—including pyrolysis-GC/MS, NMR spectroscopy, XRF, and chromatographic analysis—to identify the ink’s molecular profile. The results were unexpectedly rich.

The primary pigment was amorphous carbon, derived from high-temperature combustion of coniferous wood. Chemical markers such as retene confirmed the use of resinous species like pine or fir. This soot provided a fine, deep black base—historically consistent with Roman carbon inks.

But the analysis revealed much more. Mixed into this soot-based pigment were traces of calcium phosphate, unmistakably signaling the presence of bone black created through the calcination of animal bones. Alongside it, the researchers detected iron-bearing compounds typically linked to iron-gall ink, a formulation associated with much later periods. The ink was further stabilized by organic binders: beeswax, which acted as a thickener and contributed to the ink’s cohesion, and derivatives of animal fat or glue that enhanced its viscosity and helped it adhere effectively to papyrus or parchment. Together, these components created a chemically intricate mixture far beyond what scholars expected to find in a provincial Roman context.

This blend—carbon pigments, bone black, iron-gall elements, wax, and fats—is precisely what specialists refer to as mixed ink. It is historically attested in texts, but almost never confirmed through direct archaeological evidence. Here, the chemical fingerprint is unmistakable.

A Recipe Built for Performance

The formulation was not accidental. Each ingredient served a distinct purpose.

The carbon soot provided the intense, saturated black that made Roman writing visually striking, while the bone black enriched the color’s density and created a deeper, more opaque tone. The iron-gall components strengthened the ink’s permanence, improving its resistance to oxidation, moisture, and mechanical abrasion. Meanwhile, the beeswax and animal glue played a crucial role after application: as the ink dried, they formed a thin protective layer—almost a microscopic varnish—that sealed each letter and gave the script both gloss and resilience. This finishing effect made the writing more durable ave or military documents that faced travel, handling, or exposure to harsh conditions.

This varnish-like finish made the ink resistant to moisture—a key advantage in administrative and military contexts where documents often traveled across provinces or were exposed to harsh conditions. In effect, Roman scribes were producing a proto-oil-based ink centuries earlier than traditionally believed.

The study suggests that the ink’s creator may have used a volatile diluent—analogous to turpentine—to keep the mixture workable, a substance that would have evaporated completely after application. The result was a glossy, durable script capable of surviving both time and environmental stress, similar to the famed writing tablets from Vindolanda.

A Window into Roman Literacy and Bureaucracy

The discovery carries broader implications. Conimbriga has long been recognized as a center of literacy, evidenced by wax tablets, styluses, and accounting tools found across the site. But this inkwell adds a new dimension: it confirms that advanced writing materials were circulating even in the Empire’s western periphery.

It suggests that officials stationed in Lusitania—engineers, surveyors, tax agents, or military personnel—had access to high-quality instruments and pigments, either through state supply routes or through specialized merchants moving between frontier and hinterland.

More importantly, it demonstrates that writing was not only an intellectual skill but also a technologically supported craft, dependent on metallurgical expertise, pigment preparation, and an intricate knowledge of organic binders.

Rewriting the History of Ink

This single inkwell forces scholars to reconsider the evolution of Roman ink technology. Mixed inks may have been adopted earlier, and across a wider geographic range, than previously documented. The find shows that experimentation, hybridization, and technical cross-pollination were active forces even in small provincial centers.

Above all, the preserved ink acts as a rare, direct voice from antiquity—a material remnant of the administrative machinery that governed the Empire day by day, letter by letter.

Oliveira, C., Bottaini, C., Kaal, J. et al. Tracing literacy in Roman Conimbriga: insights from the metallurgy and ink of a Biebrich inkwell. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 17, 216 (2025). doi.org/10.1007/s12520-025-02330-3

Cover Image Credit: Residues extracted from the inkwell’s interior and analyzed using advanced laboratory techniques. C. Oliveira et al., 2025.