Thanks to advanced scientific testing, the copper alloy fragments unearthed at Snettisham, Norfolk, at one of Britain’s most significant archaeological sites have been identified as parts of a highly uncommon Iron Age helmet.

The British Museum, which had been engaged in a 15-year project to examine 14 hoards of gold, silver, and bronze torcs (stiff, twisted metal rings worn as jewelry) discovered at Snettisham, Norfolk, between 1948 and the 1990s, made this amazing discovery.

At Snettisham, near Hunstanton, on a forested hillside with a view of the northwest Norfolk coast, amazing discoveries have been made. Because so many gold and silver alloy neck rings (also known as “torcs”) and coins were found at Ken Hill, the site of the discoveries is referred to as the “gold field.” Known as the “Snettisham Treasure,” these artifacts comprise one of the greatest concentrations of Celtic art and one of the largest collections of prehistoric precious metal objects ever found. The items were discovered in at least 14 different hoards that were interred between 150 BC and 100 AD. These hoards covered the late Iron Age and early Roman eras, with the late Iron Age seeing the most activity.

Dr. Julia Farley, the Museum’s Iron Age curator and co-editor of The Snettisham Hoards, says this item is especially unique because there are only about ten known Iron Age helmets in Britain, and each one is unique.

The study’s confirmation that Iron Age metalworkers had perfected the art of mercury gilding—applying gold to bronze using a poisonous mercury-gold amalgam—was among its most startling findings. Both the helmet and the extensive collection of torcs from the Snettisham hoards were made in this way.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

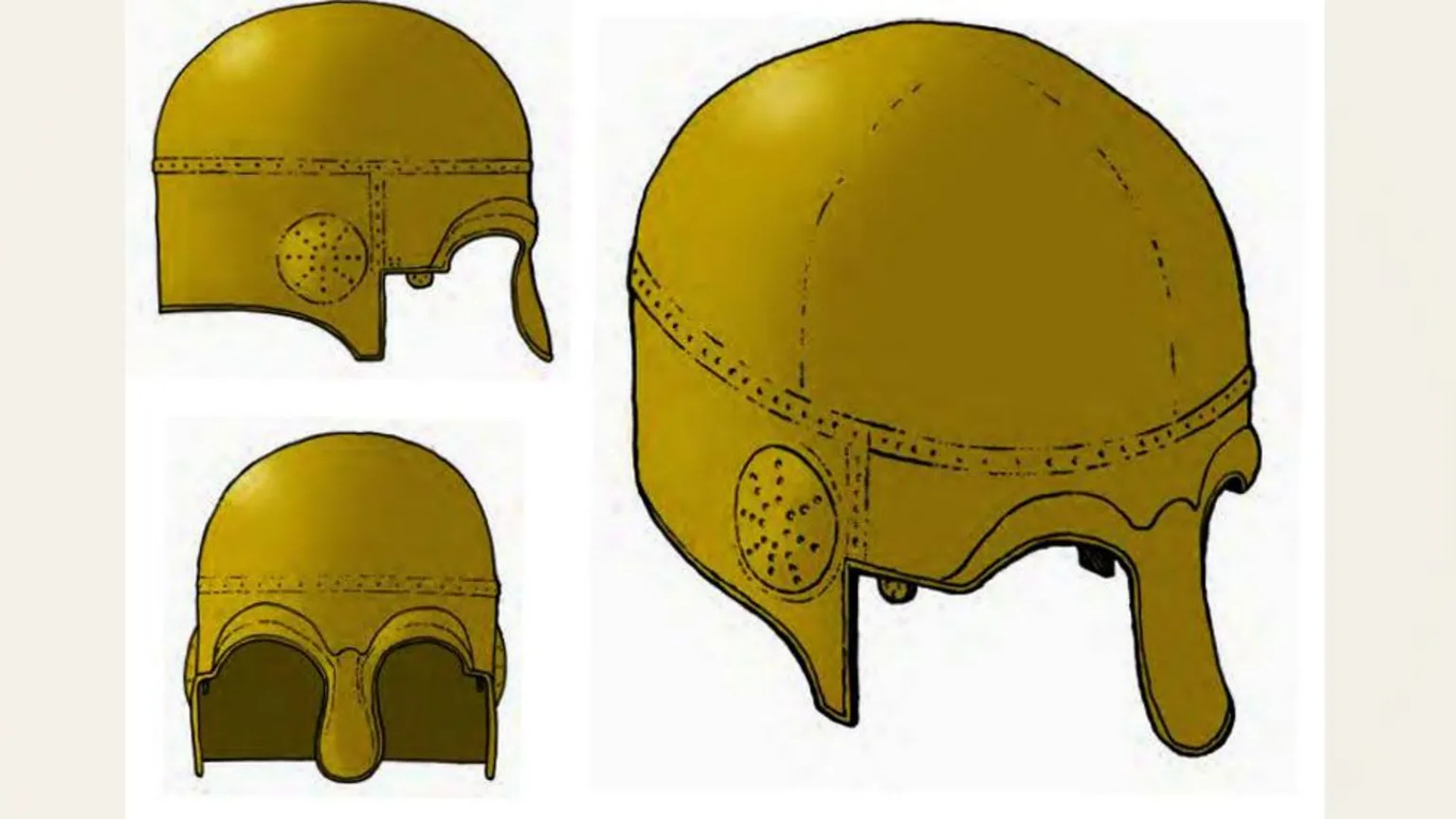

“There is a reason why everyone was so surprised in that room… helmets from Iron Age pre-Roman Britain, are just vanishingly rare,” Dr Farley, who co-edited The Snettisham Hoards with Dr Jody Joy told the BBC. “ And this one is a one-off, it’s got a kind of nasal bridge which is really unusual and these little brow pieces and it’s all hammered out from incredibly thin sheet bronze, and that’s a tremendously skilled thing to be able to do. We didn’t know they could do this in Britain 2,000 years ago”.

Dr. Joy, a former European Iron Age curator at the British Museum and one of the project’s top researchers, said the helmet fragments, which were previously believed to be pieces of a vessel, were long regarded as one of the unsolved mysteries of the Snettisham Hoards. He explained that the materials had been meticulously reconstructed by metals conservator Fleur Shearman, who had put them together like a complicated archaeological jigsaw puzzle.

Researchers believed it was probably not complete when it was put into the ground because so much was missing. Most likely, Dr. Joy thinks, it was saved for personal or sentimental reasons, and might have even been used to carry other objects (like the torcs, for example).

In the fields and forests of Ken Hill, close to Snettisham, about 400 torcs have been found, and their varied sizes indicate that they can be worn as neck, arm, or bracelet rings. The Snettisham Great Torc, one of the most intricate golden artifacts to emerge from ancient world excavations, was among the more than 60 rings that were found to be whole or nearly whole.

The British Museum, in partnership with Norwich Castle Museum, which owns a portion of the collection, began this extensive research project because the torcs had been largely left unexamined for many years.

Researchers from the British Museum were able to uncover minute details about these ringed objects, like wear patterns and polishing on areas that would have come into contact with the body or clothing, thanks to advanced scientific analysis, which included the use of electron microscopes.

The wear and tear on these valuable and valued items was significant, the researchers concluded, as it suggested they’d been worn by their owners for a long time and were prized possessions.

The team confirmed that the torcs (metal rings) were likely worn by men, women, and even younger individuals, rather than being reserved exclusively for high-status men.

Dr Farley told BBC: “Torcs are unique, individual, you wear them on your body [while] coins are mutually indistinguishable. You can give them to lots of people and they can be scattered and brought back. So the two things don’t work well together. Our theory is these torcs are too special, too unique and too important to be melted down and turned into coins, and instead people decided to have a ceremony to bring people together and put them in the ground.”

Cover Image Credit: A recreation by artist Craig Williams showing the nose and eyebrow pieces that first alerted an expert that the fragments might be a helmet. Credit: The Trustees of the British Museum