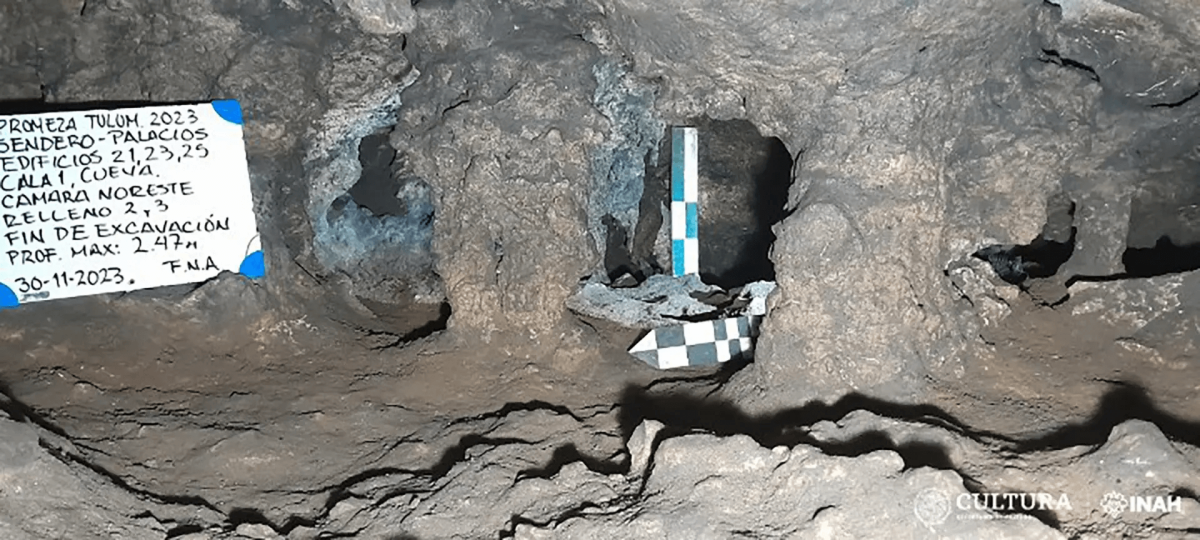

Archaeologists from the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) have discovered a hidden Maya burial chamber concealed within a cave at the archaeological complex in Tulum, Quintana Roo.

The discovery, sealed off by a massive rock deep inside Mexico’s walled city of Tulum, offers a rare glimpse into the funerary practices of this pre-Hispanic civilization.

By removing a large rock blocking the entrance to a hidden cave within the walled area of the Maya city, archaeologists uncovered the skeletal remains of several individuals.

The discovery was made during routine clearing work for a new visitor path, which is nestled between two prominent temples. A meticulously glued sea snail hinted at Maya craftsmanship, while a split human skeleton hinted at a deeper secret.

Upon removing the rock that sealed the entrance to the cavity, it was observed that it was literally splitting the skeletal remains of an individual, leaving the lower part of their body outside and the upper part inside. This would indicate that the person might have become trapped while attempting to access the cavity.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The project’s coordinator José Antonio Reyes Solís said in a statement that upon removing the boulder blocking the cave’s entrance, researchers saw that it had been splitting the ossified remains of an individual, leaving the lower part of the body on the outside and the upper part inside.

Inside the cramped cave, barely taller than half a meter, lay eight adult burials remarkably preserved by the cool, dry environment. All materials are being studied further at INAH’s Quintana Roo Center by the head of the Department of Physical Anthropology, Allan Ortega Muñoz.

As the exploration of the cave progressed, The coordinator of the archaeological research project, José Antonio Reyes Solís said, it was identified that the topography shows at least two small chambers, located in the southern and northern parts, no more than 3 meters long by 2 meters wide, and an average height of 50 centimeters.

Likewise, a large number of skeletal remains of animals associated with the burials were recorded. According to the specialists in fauna identification, who collaborate on the project, Jerónimo Avilés and Cristian Sánchez, they correspond, in a preliminary manner, to various mammals (domestic dogs, mice, opossum, blood-sucking bats, white-tailed deer, tepezcuintle, armadillo nine banded, tapir, peccary); birds of the order Galliforme, Passeriforme, Pelecaniforme, Piciforme and Charadriiforme; reptiles (loggerhead sea turtle, land turtle and iguana); fish (tiger shark, barracuda, grouper, drum fish, puffer fish, eagle ray); crustaceans (crab and cirripedians), mollusks (snail) and amphibians (frog). Some bones have cut marks and others have been worked as artifacts, like punches, needles, or fan handles, characteristic of the area.

A single ceramic “molcajete” (grinding bowl) further pinpointed the burials to the late Postclassic period (1200-1550 AD).

In three of the burials, a small mortar of the type decorated with incisions was discovered, and it has been intervened by a restorer for preservation.

Archaeologists’ testimony describes the conditions inside the cave as particularly difficult, owing to the small entryways, low ceilings, lack of natural light, and general heat and humidity. In addition to photos, a three-dimensional scan of the area will be made so that researchers and the general public can see the materials and remains in their original context.

Cover Photo: A partial view of the ancient burial chamber at Tulum. Photo: National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH)