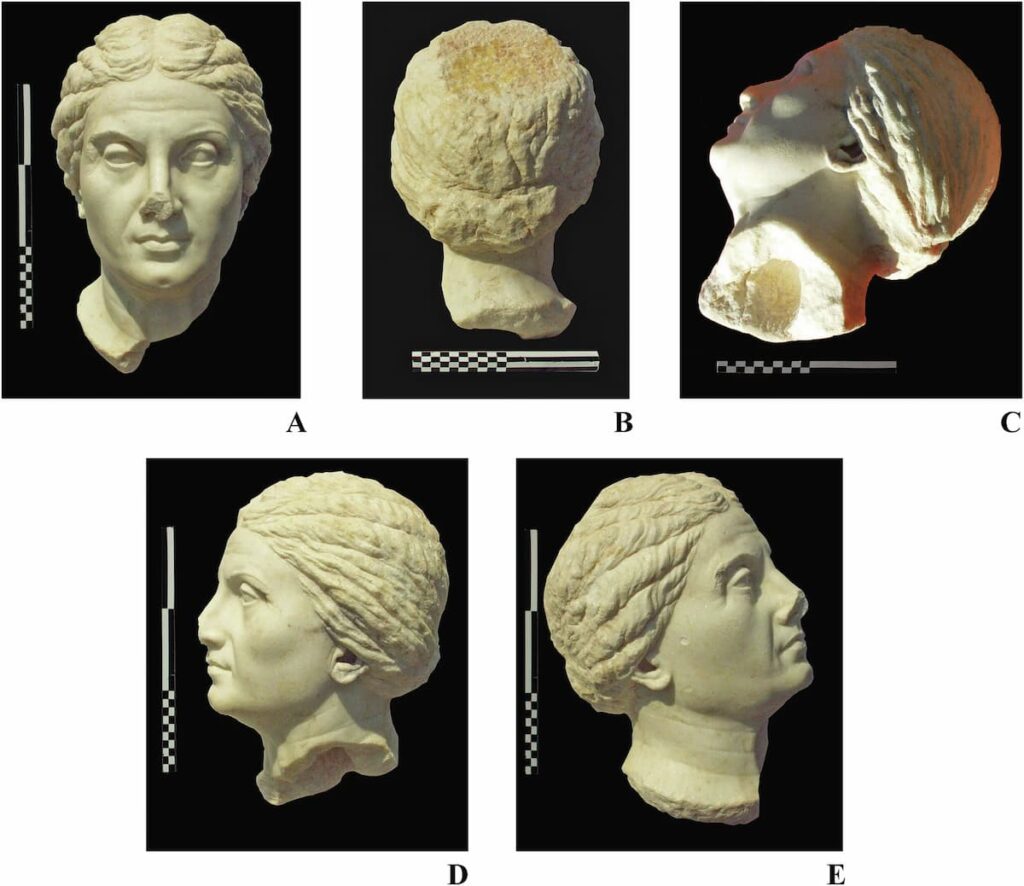

An international team of archaeologists and scientists has finally solved a mystery that began more than two decades ago. In 2003, during excavations in the ancient Greek city of Chersonesus Taurica—today’s Sevastopol in Crimea—researchers uncovered a remarkably preserved marble head of a Roman matron.

After years of interdisciplinary investigation, the sculpture has now been identified as a portrait of Laodice, a prominent woman whose political influence helped her city secure a unique status of freedom under Roman rule.

A Rare Discovery in a Clear Context

The marble head was found in a semi-basement of a large 718 m² Roman house near Chersonesus’ theater and agora. Unlike most ancient sculptures, which are often discovered without context, this piece was embedded in a well-defined archaeological layer. Alongside it were coins, pottery, and a ceramic altar depicting Artemis and Apollo. The find’s pristine context allowed scholars to date and analyze it with unusual precision.

Though damaged—its nose and parts of the face broken before burial—the head retained extraordinary detail. The lower neck included a socket for a metal dowel, proving it was once attached to a full-body statue nearly two meters tall, likely displayed in a public space such as the city’s agora. Its presence in the house fill layer suggests it was relocated after the statue was dismantled.

Science Meets Art: Unlocking the Head’s Secrets

To uncover the story behind the sculpture, researchers combined techniques from archaeology, chemistry, and art history.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Radiocarbon dating of charcoal from the surrounding strata narrowed its deposition to between AD 60 and 240, most likely the later 2nd century.

Isotopic analysis pinpointed the marble’s origin to the famed lychnites quarries of Paros in Greece, known for producing luminous, high-quality stone reserved for prestigious commissions.

Microchemical and X-ray fluorescence studies detected traces of red iron oxide pigment and evidence of ancient repair work, showing the statue was carefully maintained during its lifetime.

Toolmark analysis revealed the sculptor’s process, involving at least eleven different chisels, rasps, and abrasives.

Stylistically, the head reflects a blend of Roman realism and Greek idealism. While the sides of the face show wrinkles, sagging skin, and aged ears, the frontal features are softened and elegant. The hairstyle, a modified version of the popular “melon” coiffure with waves across the forehead, links the portrait to fashions seen in depictions of empresses like Faustina the Elder.

Identifying Laodice

The turning point came from inscriptions in Chersonesus. One pedestal honors Laodice, daughter of Heroxenos and wife of Titus Flavius Parthenocles, a man from one of the city’s wealthiest families, granted Roman citizenship under Emperor Vespasian. The monument, dated to the second quarter of the 2nd century AD, records that the city erected a statue for her in recognition of her services.

Scholars connect this honor to a pivotal event: Chersonesus’ successful bid for eleutheria, or free city status, under Emperor Antoninus Pius in the 140s AD. Earlier embassies had failed, but the eventual success secured the city’s autonomy while keeping close ties to Rome. Though the precise nature of Laodice’s role is unclear, the fact that she was commemorated with a public statue indicates her influence was considered vital.

A Woman’s Political Legacy at the Empire’s Edge

Laodice’s portrait challenges assumptions about women’s roles in Roman provincial politics. While matrons were traditionally confined to domestic spheres, her example demonstrates how elite women could shape diplomacy and civic life, even on the empire’s periphery. Chersonesus, strategically located on the Black Sea, was no ordinary city. Its survival depended on balancing independence with loyalty to Rome, and families like Laodice’s were central to that negotiation.

The choice of Parian marble underscores her elevated status: luminous, costly, and associated with divine radiance. Such material was rarely used outside major centers, highlighting the prestige both of Laodice and the city’s ambitions.

A Face from History Brought Back to Light

Today, the head stands not just as a piece of ancient art but as a historical witness. Through meticulous interdisciplinary research, Laodice has been restored from anonymity, her story revealing how women contributed to political life in Rome’s provinces.

Her portrait—serene yet realistic, monumental yet intimate—bridges cultures and eras. It embodies the convergence of Greek artistry, Roman political culture, and local civic identity. Most importantly, it ensures that Laodice’s pivotal role in securing freedom for her city is remembered nearly 2,000 years later.

As the authors of the study conclude, this discovery demonstrates how modern science can recover forgotten voices of antiquity, proving that women like Laodice were not mere spectators of history, but active participants shaping their world.

Klenina, E., Biernacki, A.B., Claveria, M. Zambrzycki, P. “An interdisciplinary study of an unknown Roman matron’s sculpture portrait from Chersonesos Taurica”. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 400 (2025). doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01975-6

Cover Image Credit: The marble head at the stratigraphic level during the moment of uncovering, the view from the southeast (Photograph by A. B. Biernacki). Klenina et al., npj Heritage Sci., 13, 400 (2025).