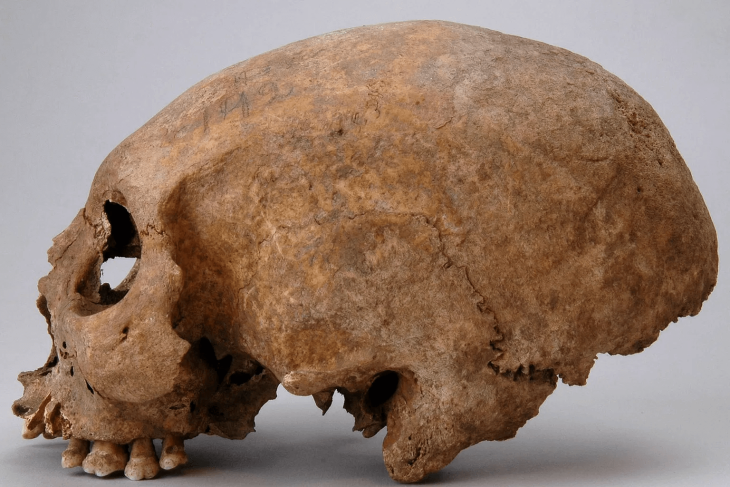

A pair of ancient skulls found along the Han River in central China have long puzzled paleoanthropologists. Were they classic Homo erectus? Or did they belong to a more mysterious lineage, possibly linked to Denisovans or even the controversial Homo longi? Now, a new study suggests the debate may be even bigger than taxonomy. The Yunxian crania could be nearly 1.77 million years old—making them the oldest securely dated Homo erectus fossils in eastern Asia.

The findings, published in Science Advances, dramatically revise the age of the Yunxian site and may reshape discussions about when early humans left Africa and how rapidly they spread across Asia.

From 800,000 Years to 1.77 Million

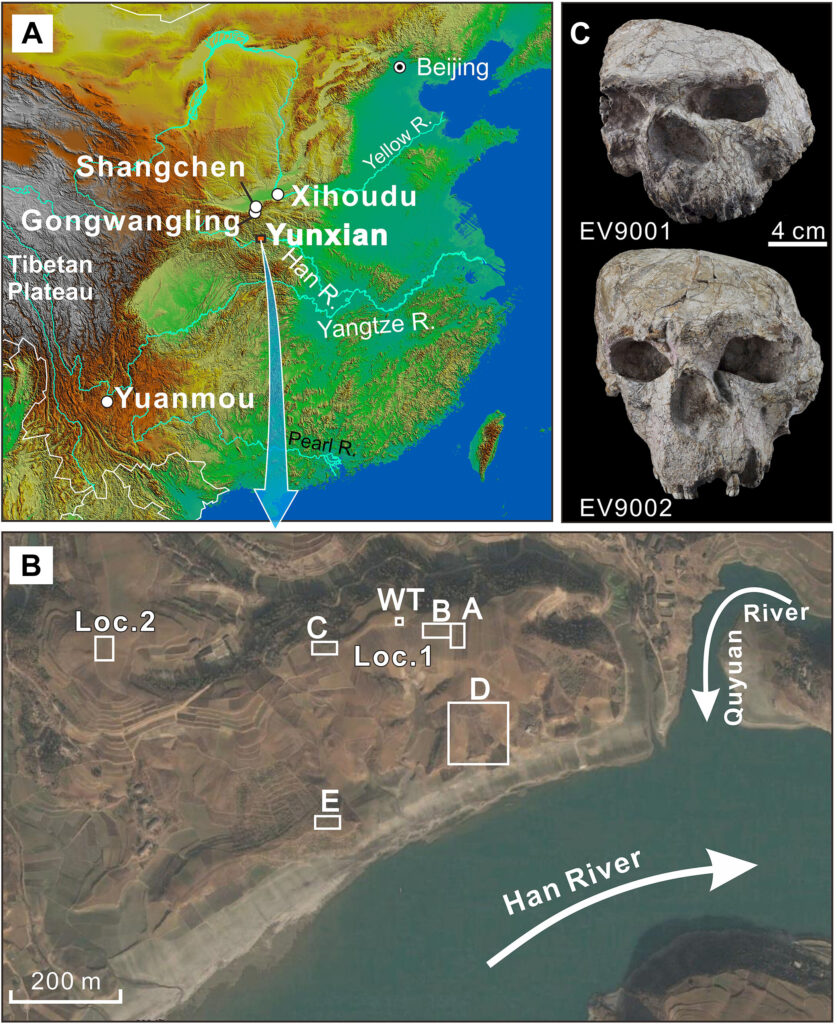

The Yunxian fossils were first discovered in the late 1980s and early 1990s in Hubei Province, central China. Over the decades, their estimated age shifted repeatedly. Early paleomagnetic and ESR (electron spin resonance) studies suggested an age between 600,000 and 800,000 years. Later analyses pushed the date back to around 1.0–1.1 million years.

Now, a Chinese–American research team led by Hua Tu, Zhongping Lai, Darryl Granger, and Christopher Bae has applied a more robust geochronological technique: isochron 26Al/10Be burial dating. By analyzing quartz gravels from the same sediment layer that yielded the hominin skulls, the team determined an age of 1.77 ± 0.08 million years.

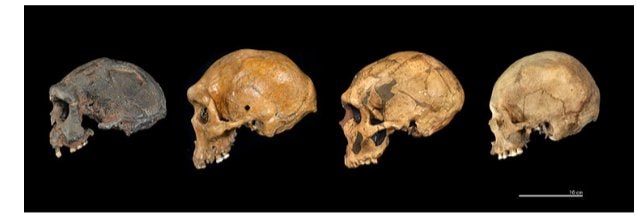

This makes the Yunxian crania the oldest in situ Homo erectus fossils discovered in eastern Asia, potentially contemporaneous with—or only slightly younger than—the famous Dmanisi fossils in Georgia (dated to 1.78–1.85 million years).

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Direct Sediment Dating Strengthens the Evidence

Cosmogenic nuclide burial dating works by measuring the radioactive decay of isotopes such as aluminum-26 and beryllium-10 in quartz. These isotopes accumulate when rocks are exposed at the Earth’s surface and begin to decay once buried. By comparing their ratios, scientists can estimate how long the sediments—and the fossils within them—have been underground.

Crucially, the Yunxian team used an isochron approach, which allows them to identify and exclude samples that may have been reworked from older deposits. This significantly improves reliability compared to earlier methods.

Because the quartz samples were taken directly from the fossil-bearing layer (C3), the new date provides a direct chronological constraint on the hominin occupation at Yunxian. This eliminates earlier uncertainties about whether the fossils were redeposited.

A Rapid Expansion Out of Africa?

If Yunxian truly dates to 1.77 million years ago, it strengthens the case for a rapid dispersal of Homo erectus across Eurasia shortly after 2 million years ago.

Until recently, Dmanisi in Georgia represented the easternmost early evidence of hominin expansion from Africa. East of Georgia, the oldest widely accepted Homo erectus fossil was from Gongwangling in China, dated to roughly 1.63 million years.

Yunxian now appears older than Gongwangling and securely dated in context—unlike the controversial Yuanmou incisors, which were surface finds and lack firm stratigraphic association.

The implication is profound: by around 1.8 million years ago, Homo erectus may already have been widely distributed across Asia, from the Caucasus to central China.

But Not Everyone Is Convinced

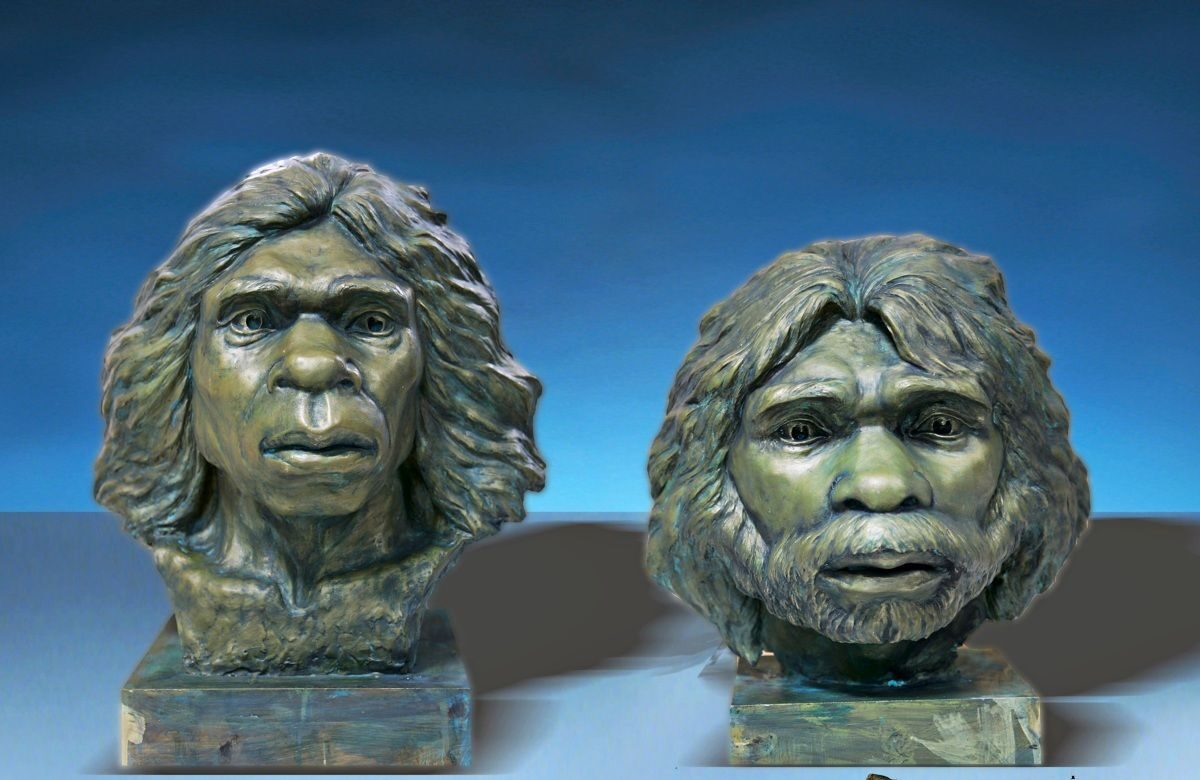

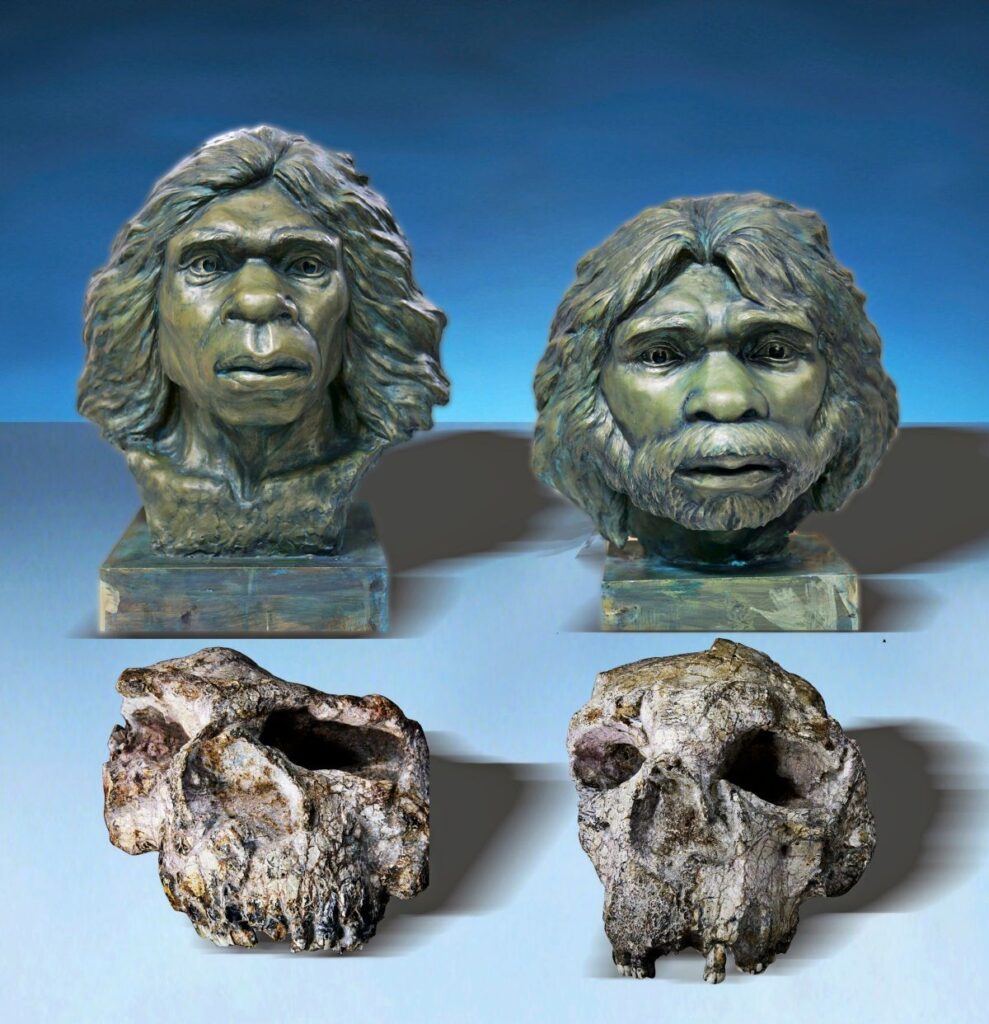

The new dates arrive amid an ongoing taxonomic debate. In 2025, a separate study using 3D morphometric analyses suggested that one of the Yunxian skulls resembled Denisovans—or even Homo longi—more than classic Homo erectus. That interpretation raised the provocative possibility that a distinct, perhaps more “modern” lineage evolved in East Asia.

Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London, a co-author of that earlier morphological study, has expressed skepticism about assigning Yunxian such a great age. According to reports in Live Science and Science News, he argues that a 1.77-million-year date may not align comfortably with the anatomical features observed.

Christopher Bae, however, maintains that most specialists who have examined the fossils firsthand consider them Homo erectus. He also cautions that certain anatomical traits may have been overemphasized in previous reconstructions.

This leaves two intertwined debates:

How old are the Yunxian fossils?

Which hominin lineage do they truly represent?

Narrowing the Archaeological Gap

The revised age also has broader implications for early human presence in China.

Stone tools from sites such as Xihoudu (~2.4 million years) and Shangchen (~2.1 million years) predate most hominin fossils in the region. For years, this created a puzzling gap between archaeological evidence and skeletal remains.

With Yunxian now dated to ~1.77 million years, that chronological gap narrows considerably. It raises a compelling question: were early occupants of northern China already Homo erectus, or could even earlier, as-yet-undiscovered hominins have been responsible for the oldest tools?

The Yunxian findings suggest that by the early Early Pleistocene, Homo erectus had already established a foothold in eastern Asia.

(A) Map of China showing Yunxian and selected early hominin sites. (B) Layout of excavation trenches at Yunxian. (C) Frontal views of the first two Yunxian crania. Credit: X. Feng, Shanxi University. Digital elevation data: gscloud.cn.

A Third Skull Could Be Key

Excavations at Yunxian resumed in 2021–2022 and led to the discovery of a third cranium, reportedly better preserved than the first two. Detailed morphometric analyses are still forthcoming.

If this new skull confirms the 1.77-million-year age and clarifies the anatomy, it may help resolve the taxonomic dispute. It could either reinforce the view that Yunxian represents early Asian Homo erectus—or complicate the evolutionary tree further.

For now, the new geochronological evidence shifts the conversation decisively backward in time.

Rethinking Human Origins in Asia

For decades, the dominant model placed the origin of Homo erectus in Africa around 1.9 million years ago, with a gradual eastward expansion. The Yunxian data support a faster, more dynamic dispersal.

If early Homo erectus reached central China by 1.77 million years ago, migration across Eurasia must have occurred relatively swiftly in evolutionary terms.

And if future analyses challenge the erectus designation altogether, the implications could be even more disruptive—suggesting parallel or complex evolutionary trajectories in East Asia.

Either way, the Yunxian skulls are no longer just a regional curiosity. They are at the center of one of paleoanthropology’s most consequential debates: when—and how—modern humanity’s deep ancestors spread across the Old World.

The answers may lie buried just meters below the Han River terrace, waiting for the next excavation season.

Tu, H., Feng, X., Luo, L., Lai, Z., Granger, D., Bae, C. J., & Shen, G. (2026). The oldest in situ Homo erectus crania in eastern Asia: The Yunxian site dates to ~1.77 Ma. Science Advances, 12(8), eady2270. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ady2270

Cover ımage Credit: Reconstruction of the Yunxian hominins: The distorted skulls from central China may belong to Homo erectus. Xiaobo Feng.