By the edge of a vanished lake in southern Sweden, archaeologists have uncovered a burial so rare it reshapes what we know about the relationship between humans, dogs, and ritual life 5,000 years ago.

In the wetlands of Logsjömossen near Järna, southeast of Stockholm, the Swedish expression “here lies the dog buried” has taken on an almost uncanny literal meaning. During large-scale archaeological investigations linked to the construction of the Ostlänken railway, researchers discovered the remarkably well-preserved remains of a Stone Age dog—intentionally placed on the lakebed and buried alongside a finely crafted bone dagger.

The find dates to the Late Neolithic period, roughly 3300–2600 BCE, and is already being described as one of the most extraordinary dog burials ever documented in northern Europe.

A burial beneath the water

Today, Logsjömossen is a waterlogged peat bog. Five millennia ago, however, it was a shallow lake fringed with human activity. Archaeological evidence shows that people built sophisticated fishing installations along the shoreline, using woven wooden barriers and fish traps that funneled fish directly into waiting baskets. It was an engineered landscape—carefully planned, maintained, and relied upon for survival.

It was into this lake that the dog was placed.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The animal was found at a depth of about 1.5 meters, some 30 to 40 meters from what would once have been the shoreline. Archaeologists believe the dog was wrapped in a hide or skin, weighed down with stones, and deliberately lowered into the water. The skull was crushed, suggesting a purposeful act rather than an accidental death.

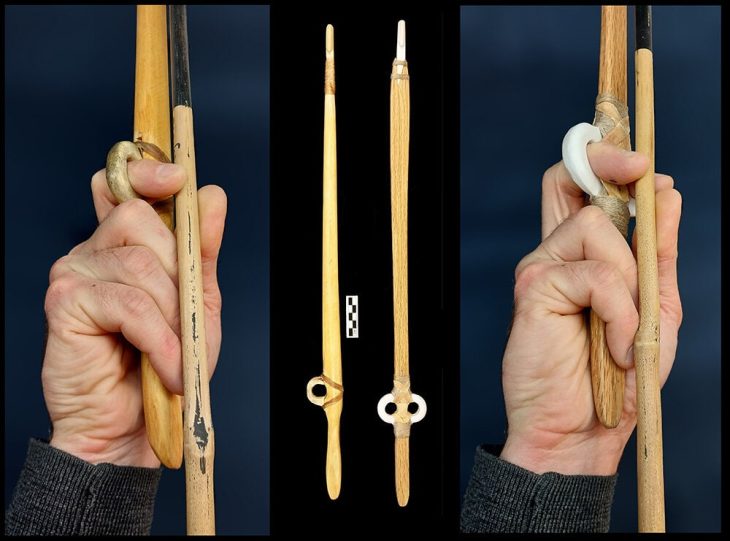

Beside the dog’s paws lay a 25-centimetre-long dagger made from elk or red deer bone. Thanks to the oxygen-poor conditions of the wetland, both the skeleton and the dagger are exceptionally well preserved. The blade looks so refined it could almost be mistaken for a modern replica.

The dog itself tells a story

Analysis shows that the animal was a large, powerfully built male dog, standing roughly 50–52 centimeters at the shoulder and between three and six years old at the time of death. Its bones indicate an active life—likely spent moving alongside people, perhaps assisting in hunting, guarding camps, or working near the fishing structures that dominated the site.

Dogs were already deeply integrated into human societies during the Stone Age, but complete dog burials are rare. A dog buried with a weapon-like object is rarer still.

“Finding an intact dog from this period is highly unusual,” says Linus Hagberg, archaeologist and project leader at Arkeologerna, part of the Swedish National Historical Museums. “That it was deposited together with a bone dagger makes the discovery almost unique.”

Ritual, symbolism, and meaning

Why bury a dog with a dagger beneath a lake?

Archaeologists are cautious about drawing firm conclusions, but the evidence strongly suggests a ritual act. Similar, though far less complete, finds have been documented elsewhere in northern Europe—most notably during investigations connected to the Fehmarn Belt tunnel, where dog skulls were deposited near fishing installations. A whole dog accompanied by a finely crafted dagger, however, sets Logsjömossen apart.

The dagger itself would not have been an everyday tool. Its craftsmanship implies symbolic value, possibly representing status, protection, or a ceremonial role. Placing it with the dog hints that the animal held a special meaning—perhaps as a companion, a guardian, or a participant in ritual practices connected to water, fishing, or the spirit world.

In many prehistoric cultures, wetlands and lakes were seen as liminal spaces, places where offerings could be made to forces beyond the human realm. The deliberate nature of the burial supports the idea that this dog was part of such a belief system.

Excavating a drowned landscape

Recovering the find was no simple task. The excavation area covered roughly 2,500 square meters and was divided into a grid of five-by-five-meter squares. The upper peat layers were saturated with water, making movement nearly impossible without extensive preparation.

To access the site, archaeologists laid down around 200 timber mats to support heavy machinery. As each square was excavated, it quickly filled with water, requiring six pumps to run around the clock. Despite the challenges, the entire area was meticulously documented using photogrammetry, creating high-resolution 3D models of every find in its original position.

“It has been a demanding fieldwork environment,” says Magnus Johansson, project manager for the Ostlänken Archaeology Project. “But the collaboration between archaeologists and construction teams worked extremely well.”

What comes next

The dog, the dagger, and associated finds have now been transported to conservation laboratories, where further analyses are underway. Radiocarbon dating, DNA sequencing, and isotope studies will help determine exactly when the dog lived, what it ate, and whether it was local or brought from elsewhere.

These answers won’t just tell the story of one animal. They will shed light on the people who lived along this lake—how they organized their economy, how they viewed animals, and how ritual was woven into everyday survival.

Logsjömossen was already known as an important Stone Age site. With the discovery of a dog buried with a dagger beneath a long-lost lake, it has become something more: a rare window into the emotional and symbolic world of prehistoric Scandinavia.

Sometimes, it turns out, there really is a dog buried there—and it has a remarkable story to tell.