No mortar, cement, or metal—yet Sardinia’s Nuragic towers have stood for 3,500 years. New scientific research reveals the ancient engineering and physics behind these gravity-defying Bronze Age structures.

For more than three millennia, the stone towers known as nuraghi have dominated the Sardinian landscape—silent sentinels rising from hills, plains, and volcanic plateaus. Built during the Bronze Age by the Nuragic civilization between roughly 1800 and 700 BCE, these enigmatic structures have long puzzled archaeologists and engineers alike. Constructed without mortar, cement, or metal reinforcement, many of them still stand remarkably intact today.

Now, a new scientific study has finally revealed the hidden engineering logic that explains their extraordinary longevity—and it turns out the secret lies not only in massive stone blocks, but in what was once dismissed as simple rubble.

A prehistoric mystery carved in stone

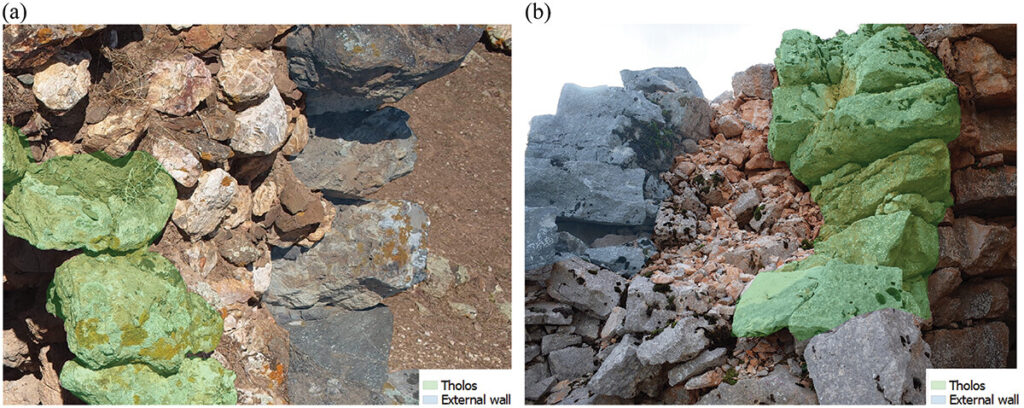

More than 8,000 nuraghi are scattered across Sardinia, ranging from simple single towers to vast, multi-towered complexes connected by walls and courtyards. At their core is a distinctive architectural form: a truncated cone-shaped external tower encasing an inner chamber roofed by a corbelled false dome, known as a tholos. Between the two stone shells lies a thick layer of loose fill—earth, pebbles, and small stones.

For decades, this fill material was considered inert ballast, little more than construction debris. Scholars debated whether the stability of the towers depended purely on the weight of their stones, on the circular geometry, or on the dome-like behavior of the tholos. What had never been rigorously tested was the mechanical role of the fill itself.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

That gap is now closed.

Simulating the past with modern physics

In a study published in the International Journal of Architectural Heritage, a team of Italian researchers led by Augusto Bortolussi applied advanced numerical modeling to a typical Nuragic tower. Using the Distinct Element Method (DEM), a technique designed to simulate structures made of individual blocks and granular materials, the researchers recreated the tower as it truly is: thousands of separate stones interacting through friction, gravity, and pressure.

The digital models precisely reflected real nuraghi dimensions—external towers up to 16 meters high and inner chambers up to six meters in diameter. Crucially, the simulations incorporated the physical behavior of the granular fill under compression.

The results were decisive.

The fill that holds everything together

The study demonstrates that the tholos is composed of stacked horizontal rings of stone blocks that, on their own, would be unstable. Without external support, these rings tend to rotate inward and spread outward under gravity, eventually collapsing.

The compacted fill material changes everything.

As the weight of the structure presses down, the loose fill compresses and generates horizontal radial pressure in all directions. This pressure acts inward on the tholos, locking its stone rings into a stable, continuous structure. In effect, the fill transforms independent blocks into a unified system capable of standing for centuries.

But physics is unforgivingly symmetrical. The same pressure that stabilizes the tholos also pushes outward—directly against the external tower.

Why the outer wall is built like a fortress

This is where the iconic cyclopean stones of the outer wall come into play. Often weighing several tons each, these massive blocks create enormous friction at their horizontal joints. That friction counteracts the outward thrust exerted by the compressed fill.

In structural terms, the external tower functions as a gigantic retaining wall or buttress. While the fill is essential for the stability of the inner chamber, it also places the outer wall under constant stress. The balance between these three elements—the tholos, the fill, and the external tower—is what keeps the entire structure standing.

The simulations quantified this balance. The static safety factor of the tholos was calculated at an exceptionally high 6.7, thanks to the stabilizing effect of the fill. By contrast, the external tower’s safety factor was 1.5, making it the most critical and vulnerable component of the system. Its stability depends almost entirely on friction between the massive stone blocks.

Reconstructing how the nuraghi were built

Understanding the statics also revealed how these towers must have been constructed. Building the tholos first would have caused it to collapse without lateral support. Constructing both stone walls and then adding fill later would not allow proper compaction.

The only feasible method, confirmed by the study, is construction by successive horizontal rings. The Nuragic builders raised one level at a time: an inner ring of tholos blocks, an outer ring of tower blocks, and then poured and compacted fill between them before moving upward.

This step-by-step technique ensured that the tholos received immediate horizontal support at every stage, while the outer wall resisted the growing pressure. It reflects a sophisticated empirical understanding of statics—achieved without mathematics, writing, or formal engineering theory.

Implications for UNESCO and conservation

The findings arrive at a crucial moment. Thirty-two Nuragic sites are currently in the process of nomination for UNESCO World Heritage status. Understanding how these towers actually work is essential for their preservation.

Any restoration that removes or alters the fill material, or interferes with the friction between outer wall blocks, could severely compromise structural stability. The study provides a scientific framework for conservation strategies that respect the original engineering logic rather than unintentionally undermining it.

A legacy of intuitive genius

The endurance of the nuraghi is not the result of chance or brute force. It is the product of a refined construction system in which every element—from the smallest pebble in the fill to the largest façade stone—plays a precise role in balancing forces.

Long before modern engineering, the Nuragic civilization mastered gravity through observation, experience, and ingenuity. Their towers stand today not only as symbols of Sardinian identity, but as universal monuments to humanity’s early understanding of physics—an understanding that modern science is only now fully uncovering.

Bortolussi, A., Dentoni, V., Levanti, C., Cara, S., Pinna, F., & Grosso, B. (2025). A Study on the Stability and Construction Techniques of Nuragic Towers. International Journal of Architectural Heritage, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15583058.2025.2595146

Cover Image Credit: Nuraghe Santu Antine in Torralba – Public Domain