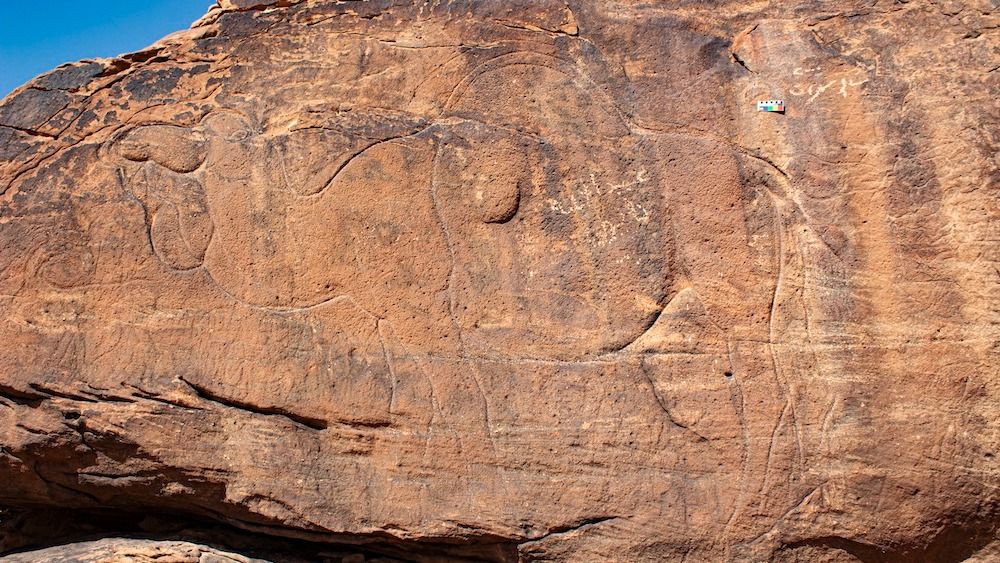

Archaeologists have found life-size camel carvings on a rock near the southern border of Saudi Arabia’s Nafud desert.

The Neolithic period of northern Arabia is known in part from the monumental stone structures and accompanying cave art, as well as the remains of hearths indicating temporary settlement. But there is much we do not know about the character and timing of settlement before the spread of animal pastoralism (c. 6000 BC).

Researchers have recently discovered new, enigmatic carvings that shed light on this ancient history.

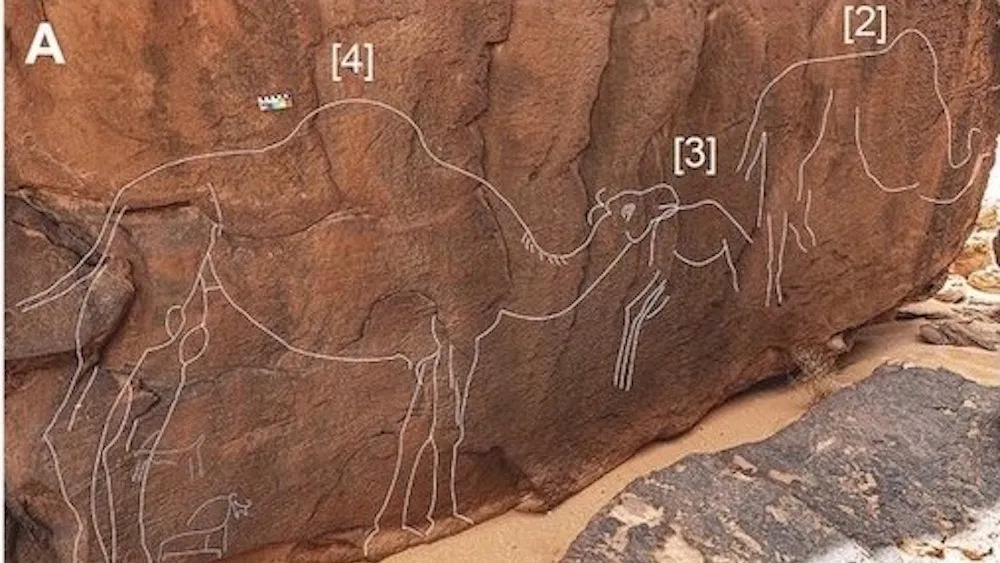

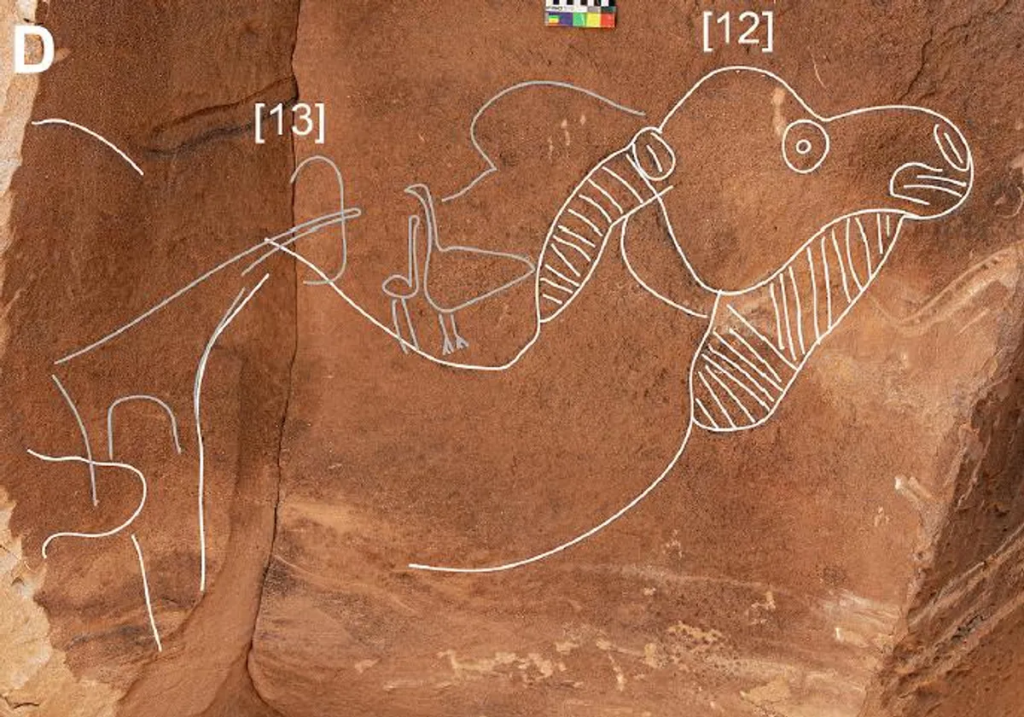

Five panels totaling nine large life-size specimens have so far been identified. The camels have frequently had other camels carved over them or had their features and proportions improved, which suggests the site was used and visited for a very long time.

The monumental artwork portrays a dozen life-size wild camels, a now-extinct species that once roamed this swath of the Arabian Peninsula desert thousands of years ago but has never received a scientific name.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The art is pretty detailed, showing predominantly male camels complete with thicker winter fur that had not been molted. These details alone suggest the art may have been created during the animal’s rutting season (between November and March).

This is the first time anyone has noticed the camel carvings on the outcropping, even though the site, known as Sahout, had been recognized by other archaeologists for some time.

“We learned about the site from another paper — but the panel was difficult to find because its location wasn’t precise, and this isn’t an easy landscape [to navigate],” study lead author Maria Guagnin, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology in Germany, told Live Science.

According to radiocarbon dating analysis of the two trenches and two ancient hearths found nearby, the Sahout site was repeatedly visited during what is called the late Pleistocene period (2.6 million to around 11,700 years ago) and the Middle Holocene (7,000 to 5,000 years ago).

The carvings have newer etchings overlapping the camels, there’s an added layer of mystery surrounding which culture created the artwork and when.

“The outcroppings contain a dense cluster of rock art from many different periods,” Guagnin said. “You can see that the carvings were done in various phases and are stylistically different.”

It also doesn’t help that most of the carvings were made inside crevices, making them difficult to access and radiocarbon date.

“For the first time we have evidence to suggest this rock art may be older than previously thought. It’s also the first time that we found a rock art site associated with early Holocene and even terminal Pleistocene archaeological deposits”, Guagnin added.

There are not many archaeological sites dated to this early period, so rock art like this may help researchers find similar ones in the future for comparison. This may be because they share similar styles of carving or because they were drawn to similar features in the landscape that also appealed to later rock art creators.

“There’s no known water source, so there might have been something else that brought people here,” Guagnin said. “Perhaps it was a good stopping point on their way to another location. It must’ve been an important location, but right now, we’re not sure why.”

More research is needed to figure out the significance of this site. The paper was published in Archaeological Research in Asia.

doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2023.100483

Cover Image credit: Maria Guagnin, et al.