More than 1,500 years after its decline, the ancient metropolis of Teotihuacan is yielding what may be one of Mesoamerica’s greatest secrets: its language. A new study by researchers Magnus Pharao Hansen and Christophe Helmke, both of the University of Copenhagen, proposes that the enigmatic texts and glyphs found among Teotihuacan’s sumptuous murals and artefacts represent an early form of Uto-Aztecan, the language family later represented by languages such as Nahuatl (of the Aztecs), Huichol, and Cora. If confirmed, this could revolutionize our understanding of who the Teotihuacanos were—and how their culture connected to later Mesoamerican societies.

The Enigma of Teotihuacan

Founded around 100 BCE and peaking by the 4th-6th centuries CE, Teotihuacan was among the most powerful urban centres of pre-Columbian America. Estimates place its population at 100,000-150,000 people. Its colossal structures—such as the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon—and wide avenues still dominate the central Mexican highland’s landscape. Yet for all its architectural and cultural grandeur, one critical mystery has persisted: What language did its inhabitants speak, and did they have a writing system?

Scholars have long debated whether the signs, symbols, and glyphic designs seen on walls, pottery, and floors constituted a full writing system—logograms, syllabograms, phonetic signs—or were merely emblematic or decorative. Candidate proposals for the underlying language have ranged from early Nahuatl, to Totonakan, to Oto-Manguean and others.

The New Study: Methods & Findings

Helmke and Hansen’s forthcoming paper, “The Language of Teotihuacan Writing”, accepted for publication in Current Anthropology (in press, 2025), argues that Teotihuacan did indeed have a writing system that encodes an early Uto-Aztecan language.

Key pieces of the research include:

Reconstruction of an earlier stage of Uto-Aztecan, especially of Nahuan (the branch leading to Nahuatl), Coracholan (Cora and Huichol), and related languages. This allows comparison of likely phonetic values of signs.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

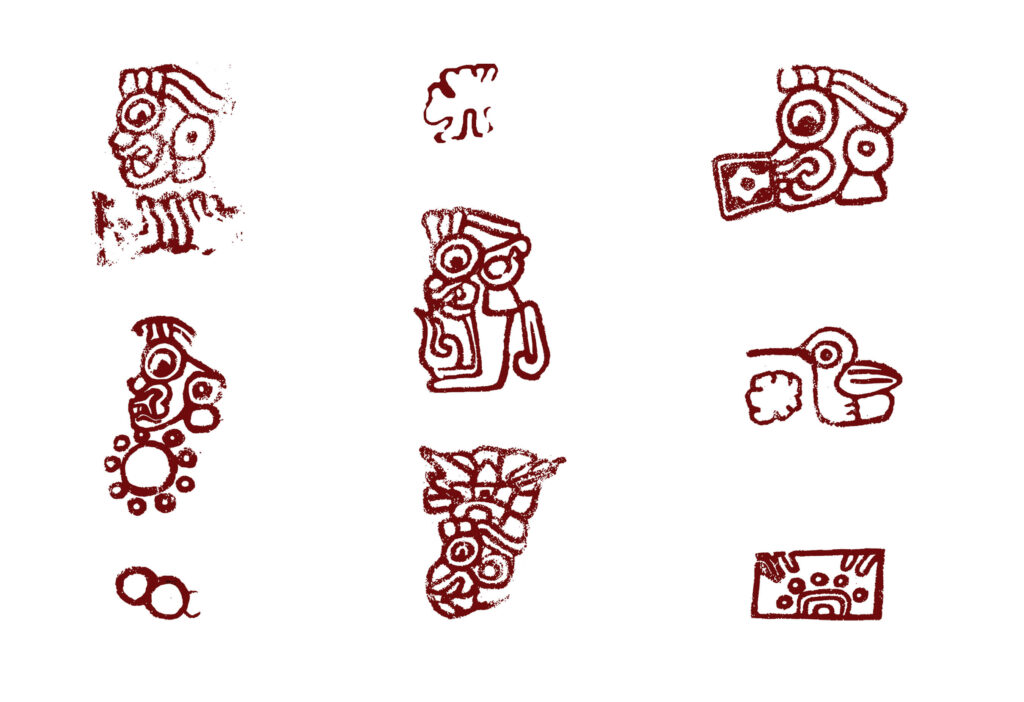

Building a catalogue of Teotihuacan glyphs and signs, their distribution, when and where they appear (murals, decorated pottery, murals etc.), and their graphic features.

Applying a rebus-like method, whereby certain glyphs are used not just as pictorial/logogrammatic representations (e.g. a coyote sign meaning “coyote”), but also for their sound value—so images stand for sounds and are combined, just like later scripts in Mesoamerica.

One of their significant claims is that Teotihuacan texts do more than simply decorate—they encode linguistic data. Some logograms are used with phonetic readings, in contexts beyond their pictorial meaning. Also, they suggest that Uto-Aztecan dialects (especially the Nahuan branch) were already present in Central Mexico during the Classic Period, which pushes back the arrival or local development of Nahuatl-related languages.

Implications: Rethinking Teotihuacan’s Place in Mesoamerica

If this proposal holds up under further scrutiny, there are several major implications:

Identity of Teotihuacan’s people

This research strengthens the argument that the inhabitants of Teotihuacan were early Uto-Aztecan speakers, possibly direct ancestors of later Nahuatl speakers. That suggests continuity or early settlement rather than later migrations being wholly responsible for Nahuatl presence.

Linguistic history

The findings may shift models of when and where Nahuan (and related Uto-Aztecan) languages developed. The researchers have already reconstructed phonological features of proto-Nahuatl and related dialects to match the time-frame of Classic Teotihuacan.

Writing system evolution in Mesoamerica

Teotihuacan may now be counted among the Mesoamerican societies with true writing systems, not merely symbolic art. Understanding how its system relates (structurally and graphically) to Maya writing, later Nahua scripts, or Oto-Manguean systems will enrich knowledge of how writing developed, spread, and was used.

Archaeology, iconography, inscriptions

It may allow new readings of inscriptions, glyphs, and murals—both those already discovered and future finds. Walls, pottery, painted floors, etc., could reveal names, place-names, ritual texts if one can map sign usage and sound values accurately.

What Still Needs to Be Done

Helmke and Hansen are clear that their findings are not yet definitive. Some of the challenges remaining:

The corpus is small: there arelimited examples of texts, decorated artefacts, murals with inscriptions. The current number of contexts where glyphs are found is modest. More specimens would help confirm patterns and readings.

More sign repetition in diverse contexts: ideally, the same glyph used in similar ways across artefacts, to test the consistency of readings.

Further comparative linguistic work: reconstructive linguistics is known to have uncertainties, particularly over time depth. Verifying phonetic reconstructions, variations among dialects, and sound changes is complex.

Engagement with the broader scholarly community: workshops, peer review, alternative hypotheses must be considered carefully. The paper is scheduled for publication accompanied by commentary from other experts.

How This Research Compares to Earlier Hypotheses

Earlier studies have considered various possible languages for Teotihuacan:

Nahuatl / Nahuan branch of Uto-Aztecan has been a perennial candidate. Some scholars argued for early Nahuatl presence in Central.

Totonakan, Oto-Manguean, and Mije-Sokean language families have also been proposed. These alternatives were grounded in typological features, grammatical guessing, or lexical comparisons.

What Helmke & Hansen do differently is reconstructing pre-Nahuatl / proto-Uto-Aztecan forms that fit the time period, matching them to sign usage, and offering some phonetic readings for certain glyphs. This both narrows down the viable options and provides more specific evidence, rather than broad typological fits.

Conclusion

The research of Magnus Pharao Hansen and Christophe Helmke represents a major advance toward deciphering the Teotihuacan writing system and understanding the language of its people. While more work remains to solidify their readings and confirm hypotheses, the identification of an early Uto-Aztecan language at Teotihuacan—if validated—reshapes long-held notions about migration, language spread, written tradition, and cultural continuity in ancient Mesoamerica.

This discovery, combining epigraphy, iconography, phonetic reconstruction, and comparative linguistics, opens a path toward finally answering one of the most compelling archaeological questions: Who were the people of Teotihuacan, and what did they say?

‘The Language of Teotihuacan Writing’ has been published in the journal Current Anthropology.

Cover Image Credit: Avenue of the Dead, Teotihuacán, Mexico. Public Domain