More than 4,000 years ago, long before highways and petroleum refineries, Sumerian craftspeople in southern Mesopotamia were perfecting material formulas that mirror modern asphalt engineering.

A new study published in Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports reveals that artisans at the ancient city of Abu Tbeirah followed precise, repeatable “technological recipes” when producing bitumen-based materials. Their methods—carefully balancing plant fibers, mineral powders, and controlled heating—anticipate principles that engineers still use today.

Cracking Open Ancient Black Gold

Bitumen, a natural petroleum-based substance, was indispensable in ancient Mesopotamia. It sealed boats, waterproofed baskets, glued tools, and was molded into transportable blocks for trade. But raw bitumen had problems: it could soften in heat, crack when brittle, or become too sticky to handle.

Rather than using it as-is, Sumerian craftspeople engineered it.

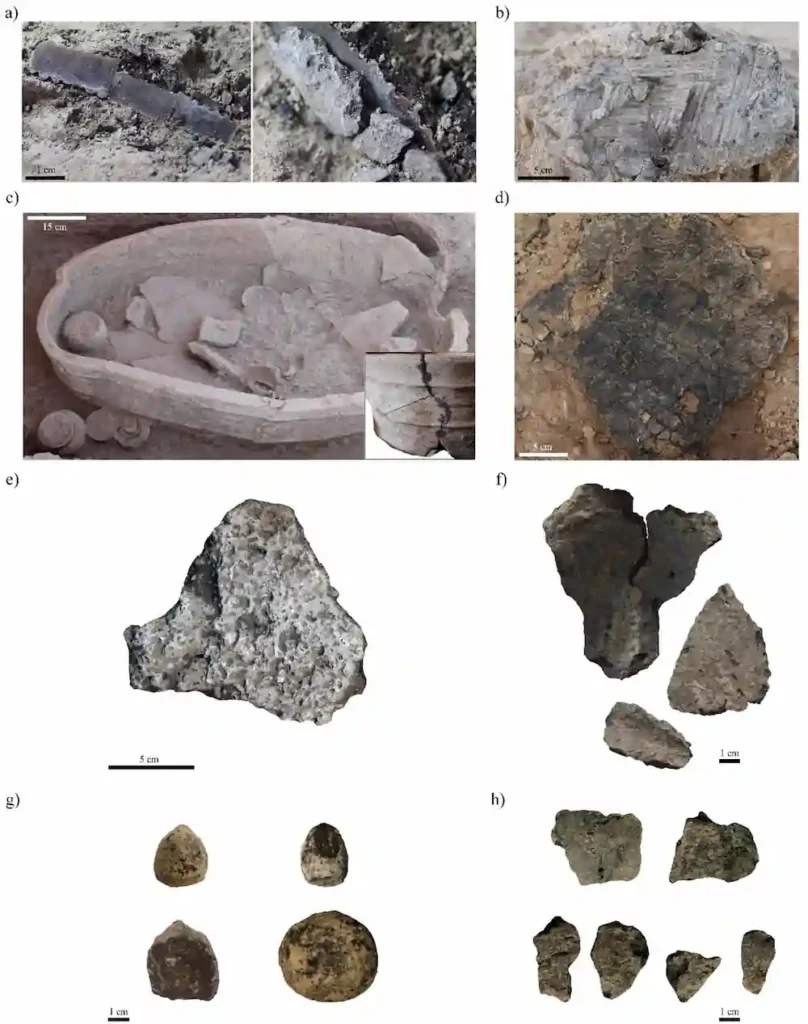

Researchers analyzed 59 bitumen-based samples recovered from Abu Tbeirah, a major third-millennium BCE settlement located near the famous city of Ur. Using high-resolution digital microscopy and machine-learning-assisted image processing, they examined the internal structure of the materials—without damaging the artifacts.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Instead of focusing only on chemical composition, the team studied mesostructure: pores, vegetal fibers, mineral inclusions, and how these elements were distributed. The microscopic architecture revealed intentional design choices.

Four Recipes, Four Functions

Statistical analysis uncovered distinct compositional clusters corresponding to different uses.

- Tool Adhesives

Bitumen used to attach flint blades to sickles contained abundant plant fibers and minimal mineral content. The fibers reinforced the adhesive, increasing flexibility and preventing cracks under repeated agricultural stress. It was, essentially, fiber-reinforced glue. - Standardized Trade Ingots

Rectangular blocks—likely used for storage or trade—showed remarkably consistent formulas. Both vegetal and inorganic materials were systematically present. These ingots may have functioned as semi-finished products, transported and later reheated and modified depending on local needs. Their uniformity suggests standardized production and possibly specialized workshops. - Spherical Objects

Previously mysterious round bitumen objects turned out to have highly homogeneous internal structures rich in mineral inclusions. Researchers suggest they may have been compact reserves—leftover processed bitumen shaped into convenient forms for later reuse. - Sealants and Waterproofing Agents

Samples associated with reed structures and containers displayed balanced combinations of plant and mineral additives. This blend optimized waterproofing while maintaining durability—critical in the marshy landscapes of southern Mesopotamia.

Across all categories, porosity patterns also varied in meaningful ways, revealing differences in heating cycles, mixing intensity, and recycling practices.

An Ancient Circular Economy

The study also uncovered evidence of systematic recycling. Bitumen was too valuable to waste. Archaeological and textual evidence suggests it was recovered from broken tools, dismantled boats, and production scraps.

Repeated reheating left microscopic signatures within the material. However, too many heating cycles made the composite brittle, limiting reuse. To compensate, craftspeople adjusted the recipe—adding more fibers or mineral fillers to restore workable properties.

In effect, Sumerians were practicing resource management strategies that resemble today’s circular economy principles.

Striking Parallels with Modern Asphalt

Modern engineers enhance asphalt with cellulose, hemp, or synthetic fibers to improve crack resistance. Mineral fillers such as limestone powder regulate viscosity and increase durability.

The similarities are not coincidental but reveal convergent engineering logic. Faced with the same material—bitumen—ancient and modern builders discovered similar solutions: control heat, add reinforcement, balance flexibility with strength.

The Sumerians did not have laboratory instruments or materials science textbooks. What they had was systematic experimentation and intergenerational knowledge transfer.

Technology Without Theory

The research marks a methodological breakthrough as well. While most previous studies focused on chemical and isotopic analyses of ancient bitumen, this project applied computational image analysis—techniques commonly used in modern pavement engineering—to archaeological materials.

By combining microscopy, automated feature extraction, and multivariate statistics, researchers reconstructed ancient production sequences in a non-destructive way.

The findings challenge outdated assumptions that early urban societies relied on simple or improvised technologies. Instead, they reveal a sophisticated material culture grounded in empirical observation, standardization, and technical specialization.

In the sticky black substance that sealed their boats and bound their tools, Sumerian craftspeople encoded a practical understanding of material science—one refined enough to echo across four millennia.

V. Caruso, C. Scatigno, S. Giampaolo, A. Tufari, et al., Decoding Sumerian craft technologies: morphological image processing and mesoscopic feature analysis of archaeological bitumen-based composites. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 70, April 2026, 105607. doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2026.105607

Cover Image Credit: Ruins of the ancient city of Ur in southern Iraq. In the Sumerian period, houses were built from mudbrick and clay plaster, while larger structures were reinforced with bitumen and reed layers to enhance durability and structural stability. Public Domain