When archaeologists resumed work this year at the Palace of Archanes—one of Crete’s most enigmatic Minoan centers—they did not expect that a peculiar, slanted wall long dismissed as an architectural oddity would rewrite understandings of Minoan engineering. Yet the 2025 excavation season has now revealed that this unusual double wall, tucked into the palace’s central courtyard, was a purpose-built protective system designed to shield the complex from catastrophic landslides.

The discovery, announced by the Greek Ministry of Culture, underscores a sophisticated understanding of geological risk management in the Middle Bronze Age, and reveals a level of architectural planning that rivals the most refined achievements of Knossos and Phaistos.

A slanted mystery that never fit the puzzle

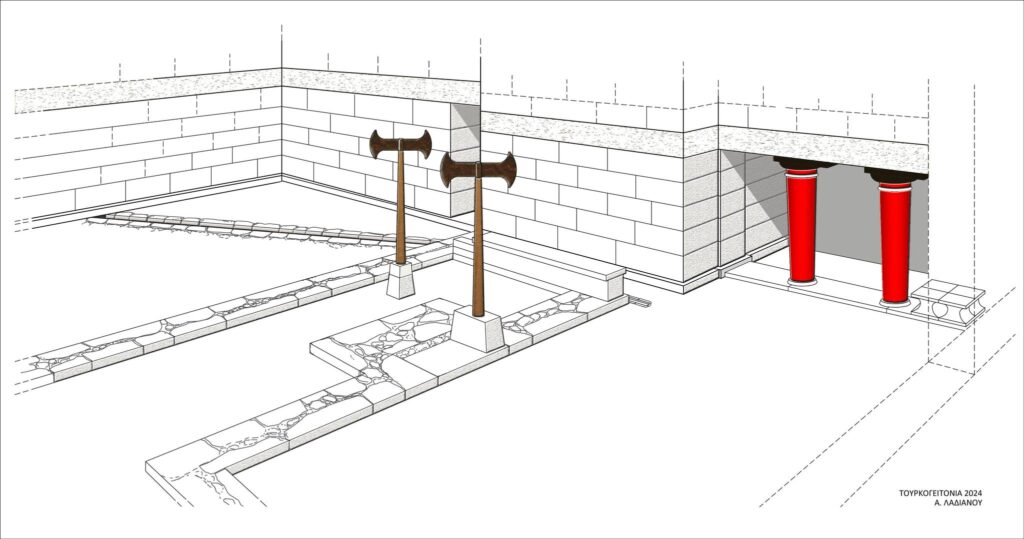

For decades, the existence of a skewed, inward-leaning wall at Archanes puzzled researchers. Built of unworked, irregular stones and apparently closing off a section of the courtyard, it lacked the refinement expected of Minoan palatial craftsmanship. Its crude construction raised difficult questions: Was it a later addition? A makeshift barrier? Or a structural experiment gone wrong?

Systematic study during the 2025 campaign—conducted by the Archaeological Society under the scientific direction of Dr. Polina Sapouna-Ellis, with archaeologists Dimitris Kokkinakos and Persefoni Xylouri—finally clarified its role. Geological modelling, supported by the expertise of geologist Dr. Charalambos Fassoulas, demonstrated that the palace lies directly beneath a steep rock face prone to rockfall. The slanted inner wall turned out to be a concealed retaining structure built to absorb impact and stabilize the slope above.

Its appearance, however, did not satisfy Minoan aesthetic standards. To preserve the visual harmony of the monumental courtyard, architects erected a second wall tightly attached to the first—this time using carefully carved porous stone blocks matching the palace’s architectural vocabulary. From the courtyard, only this elegant outer wall was visible; the rougher inner wall remained hidden, performing its silent protective function.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

New insight into a continuously occupied ritual and administrative center

Excavations along the upper levels of this double wall revealed layers rich in Mycenaean pottery—including kylikes—and traces of later historical activity. These finds reinforce evidence that Archanes remained inhabited long after the palace’s final destruction around 1450 BC. The site’s long life is already well documented: it was first devastated by an earthquake around 1700 BC, rebuilt, and then flourished until the mid-15th century, after which Mycenaean and later occupants continued to reuse the area.

In the southeastern section of the excavation, archaeologists exposed a new passage linking the Central Courtyard to the palace’s easternmost rooms. The space is divided by stone slabs, one of which carries a large trapezoidal stone with sockets that once held a parapet later destroyed by a Mycenaean wall.

But the most intriguing object found here is a naturally shaped stone with subtle anthropomorphic features. Its discovery on a floor where it had fallen from an upper level suggests that it once belonged to a cultic installation. According to the research team, it likely formed part of a “fetish shrine”—a ritual corner similar to the one uncovered at Knossos. Such shrines, characterized by natural stones considered animate or divine, offer rare insight into the intimate religious practices of Minoan households and palaces.

Reconstructing the palace’s elite quarters

Finds from the 2023–2025 research campaigns increasingly point to a luxurious, multi-story elite wing occupying the palace’s northern sector. Excavators documented a complex network of rooms connected by corridors, decorated with fresco fragments, gypsum jambs, and mortar-coated walls. Floors composed of schist slabs still carry their characteristic Minoan decorative borders—raised mortar strips that once framed each slab, a detail found across Crete but preserved exceptionally well at Archanes.

The resulting picture is of a monumental building designed not only for administrative and ceremonial use but also for high-status residence. Its reconstruction in three stories, confirmed through architectural sequencing, supports long-held theories that Archanes functioned as a secondary palace closely tied to Knossos.

A palace hiding in plain sight

Archanes occupies an unusual position in the history of Minoan archaeology. The palace sits beneath the modern town—specifically in the Tourkogeitonia district—making excavation difficult and fragmentary. Sir Arthur Evans first recognized signs of monumental Minoan structures here in the early 20th century, identifying wall surfaces and discovering an impressive circular aqueduct. He also believed that elite grave goods found nearby, now housed in the Ashmolean Museum, originated from this region.

It was only through the meticulous surveys of Yiannis and Effie Sakellarakis, who examined the basements of modern houses and mapped surviving walls, that the core of the palace was precisely located. Their work confirmed that earlier archaeologists had been searching in the wrong place for Evans’s rumored “summer palace.” What they identified instead was something far more significant: a major Minoan palatial center with structural innovations unseen elsewhere on Crete.

Engineering, ritual, and resilience

The newly identified landslide-protection system adds a fresh layer to this narrative. It demonstrates that Minoan architects not only built monumental structures but also integrated advanced risk-mitigation strategies tailored to the island’s geology. At Archanes, engineering logic and aesthetic ideals coexisted seamlessly—hidden walls absorbed destructive forces, while visible façades maintained the palace’s harmonious visual identity.

As the 2025 excavation season concludes, the Palace of Archanes emerges as a site where ritual practice, elite life, and pioneering engineering intersect. The slanted double wall, once a curiosity, is now recognized as a testament to Minoan ingenuity: a quiet reminder that behind the civilization’s famed artistry lay a profound understanding of the natural world—and the architectural creativity to master it.

Cover Image Credit: Greek Ministry of Culture