Researchers made a groundbreaking discovery of what is thought to be the world’s largest prehistoric rock art. Enormous engraved rock art of anacondas, rodents, giant Amazonian centipedes, and other animals along the Orinoco River in Colombia and Venezuela may have been used to mark territory 2,000 years ago.

Rock engravings recorded by researchers from Bournemouth University (UK), University College London (UK) and Universidad de los Andes (Colombia), believe this is the largest single rock engraving recorded anywhere in the world. Some of the engravings are tens of meters long – with the largest measuring more than 40m in length.

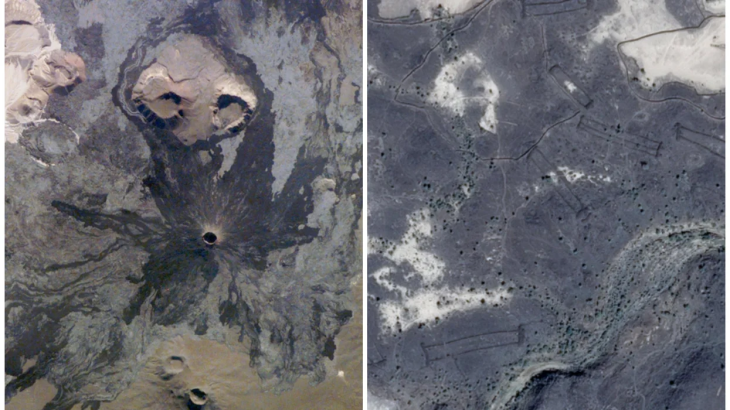

While some of the locations were previously known, the team has used drone photography to map 14 sites of monumental rock engravings, which are defined as those that are more than four meters wide or high, and has also found several more.

While it is difficult to date rock engravings, similar motifs used on pottery found in the area indicate that they were created anywhere up to 2,000 years ago, although possibly much older. Many of the largest engravings are of snakes, believed to be boa constrictors or anacondas, which played an important role in the myths and beliefs of the local Indigenous population.

Their size makes them visible from a distance, suggesting they were used as ancient signposts that told travelers along the prehistoric trade route whose territory they were entering and leaving.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The new findings were published on Monday in Antiquity.

The engravings may represent mythological traditions that continue today, says archaeologist and anthropologist Carlos Castaño-Uribe, scientific director of the Caribbean Environmental Heritage Foundation in Colombia.

Lead author Dr Phil Riris, Senior Lecturer in Archaeological Environmental Modelling at Bournemouth University, said: “These monumental sites are truly big, impressive sites, which we believe were meant to be seen from some distance away.

“We know that anacondas and boas are associated with not just the creator deity of some of Indigenous groups in the region, but that they are also seen as lethal beings that can kill people and large animals.

“We believe the engravings could have been used by prehistoric groups as a way to mark territory, letting people know that this is where they live and that appropriate behaviour is expected.

“Snakes are generally interpreted as quite threatening, so where the rock art is located could be a signal that these are places where you need to mind your manners.”

The researchers located 157 rock art locations between the upriver Maipures Rapids and the downstream Colombian city of Puerto Carreño. Of these, more than a dozen had engravings longer than four meters (about 13 feet). The largest is the anaconda, which is over 40 meters (roughly 130 feet) in length. Riris says it is likely the largest known prehistoric rock engraving in the world.

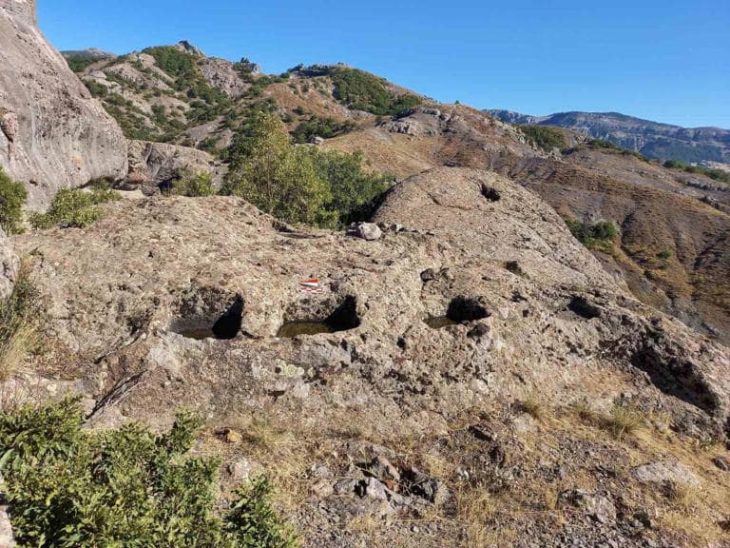

The images were produced by chipping away the granite surface—which in this region is stained dark by untold years of bacterial growth—to reveal the lighter rock beneath.

Some of the engravings are at usually below the waterline and only visible in seasons when the river is low, while others are located a short distance away from the banks, on large granite outcrops that stand over the savanna landscape of the river basin. There are also engravings, and occasionally paintings, in natural rock shelters near the river.

Dr José R. Oliver, Reader in Latin American Archaeology at University College London Institute of Archaeology, added: “The engravings are mainly concentrated along a stretch of the Orinoco River called the Atures Rapids, which would have been an important prehistoric trade and travel route.

“We think that they are meant to be seen specifically from the Orinoco because most travel at the time would have been on the river. Archaeology tells us that it was it was a diverse environment and there was a lot of trade and interaction.

“This means it would have been a key point of contact, and so making your mark could have been all the more important because of that – marking out your local identity and letting visitors know that you are here.”

The research team concludes that it is vital that these monumental rock art sites are protected to ensure their preservation and continued study, with the Indigenous peoples of the Orinoco region central to this process.

Dr Natalia Lozada Mendieta from Universidad de los Andes said: “We’ve registered these sites with the Colombian and Venezuelan national heritage bodies as a matter of course, but some of the communities around it feel a very strong connection to the rock art. Moving forward, we believe they are likely to be the best custodians.”

The research was funded by the Leverhulme Trust, The Society of Antiquaries of London, Universidad de los Andes, the Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas Nacionales (Colombia), and the British Academy.

Cover Photo: Telephoto shot of monumental rock art of snake body in Colombia, humans for scale. Photo: Dr José Oliver