Archaeologists in Norway have uncovered a rare and fascinating piece of history: a 9,000-year-old hammer dating back to the Stone Age. The discovery, made during an excavation in Horten, Eastern Norway, offers an extraordinary glimpse into early human life, settlement patterns, and craftsmanship in Scandinavia.

The excavation, led by archaeologist Silje Hårstad from the Museum of Cultural History, revealed not only the hammer but also the remains of a settlement, including traces of a house, thousands of artifacts, and preserved bone fragments. What began as a routine dig before the construction of a bike path has become one of the most significant archaeological finds in the region in recent years.

A Hammer From the Distant Past

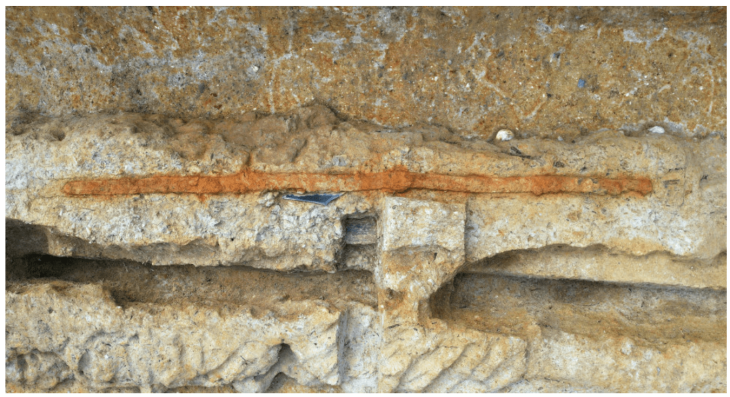

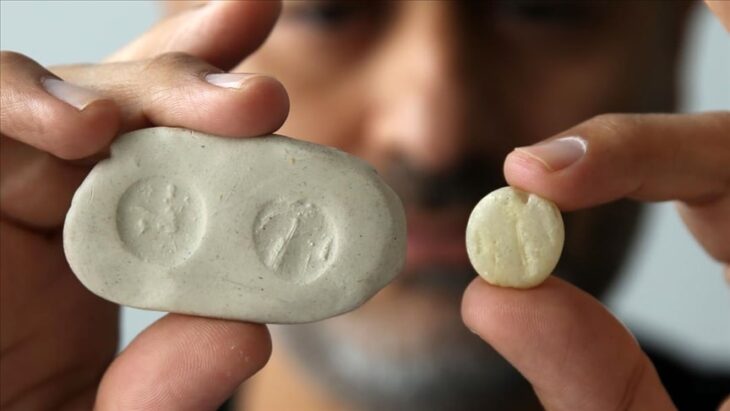

The most remarkable discovery from the site is half of a shaft-hole club head, essentially a Stone Age hammer. Unlike an ordinary rock, the stone bore unmistakable signs of human craftsmanship: a carefully drilled hole where a wooden shaft would once have been attached.

“It’s one of the best finds from this site,” said Hårstad. “It was round, slightly oval, with a distinct drilled hole in the middle. It’s obvious that it was shaped by humans.”

The hole itself was created using a primitive but effective technique. Archaeologists believe Stone Age people may have used hollowed-out animal bones, such as deer or moose, combined with sand and water to slowly grind through the stone. This labor-intensive process shows not only patience but also a high degree of technological skill for the era.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Tool, Weapon, or Symbol?

While the hammer may have been used as a tool, its function could have been more complex. Some shaft-hole clubs discovered elsewhere are shaped like stars, crosses, or decorated with engravings, suggesting symbolic or ceremonial importance.

“This one shows light wear and crushing marks on one side, which suggests it was used as a tool,” Hårstad explained. “It may have been used to pound or soften fibers. In essence, it is a Stone Age hammer.”

Archaeologist Knut Andreas Bergsvik from the University of Bergen notes that such artifacts fall into three categories: simple club heads like the one found in Horten, more elaborate star-shaped designs, and versions made from organic materials such as whale bone or wood. The latter rarely survive due to decay, meaning many examples may have disappeared over millennia.

Some decorated versions likely served as status symbols for skilled hunters or leaders, offering insights into social hierarchies and cultural practices during the Early Stone Age.

A Settlement Frozen in Time

The hammer is only part of the story. Excavations revealed more than 5,000 artifacts, including axes, fishhook fragments, tools, and animal bones. Even more significantly, archaeologists discovered the remains of a small hut, about 10 square meters in size, suggesting a semi-permanent home rather than a temporary shelter.

“This is one of the most enjoyable excavations I’ve ever taken part in from this period,” Hårstad said. “It’s like a little time capsule.”

Samples taken from the hut floor may show evidence of bark mats used as flooring. Meanwhile, bones discovered near the shoreline indicate the site may have served as a butchering or cooking area, as well as a place for crafting tools.

Diet, Hazelnuts, and Daily Life

The bone fragments recovered at Horten will undergo detailed analysis to determine what animals the settlers hunted and consumed. Nearby sites from the same period show diets rich in seafood such as seals, whales, seabirds, and fish. Archaeologists hope to see whether this community also relied on land animals.

To establish precise dating, researchers will use carbon dating on charred hazelnuts found at the site. Hazelnuts were a common food during the Stone Age and are often discovered at settlements across Scandinavia. Because hazelnuts grow and are consumed within a single season, they provide more accurate dating results than wood, which can live for centuries.

Evidence of Cultural Change

The finds in Horten also illustrate a major cultural shift during the Early Stone Age, around 9,000 years ago.

Earlier groups were highly mobile, traveling great distances with little focus on fishing or permanent housing. By contrast, the Horten settlement shows evidence of people staying longer in one location, building sturdier homes, relying more heavily on fishing, and producing new types of tools.

“This settlement is so important because it demonstrates the technological and economic transformation of the time,” Bergsvik explained. “People were no longer just moving from place to place. They were investing resources into more permanent communities.”

A Window Into Norway’s Prehistoric Past

The discovery of the Stone Age hammer, combined with thousands of other artifacts, provides a rare and detailed look at life in Norway nearly 10,000 years ago. In a region where acidic soil often destroys organic remains, finding preserved bone fragments and tool-making evidence is especially significant.

From the craftsmanship of the hammer to the charred hazelnuts and remains of a small hut, the Horten excavation sheds light on how Stone Age communities lived, worked, and adapted to their environment.

As further analyses continue, archaeologists hope to unlock more secrets from this extraordinary site. For now, the hammer stands as a powerful reminder that even a simple stone, when shaped by human hands, can carry stories across millennia.

Cover Image Credit: Silje Hårstad / Museum of Cultural History