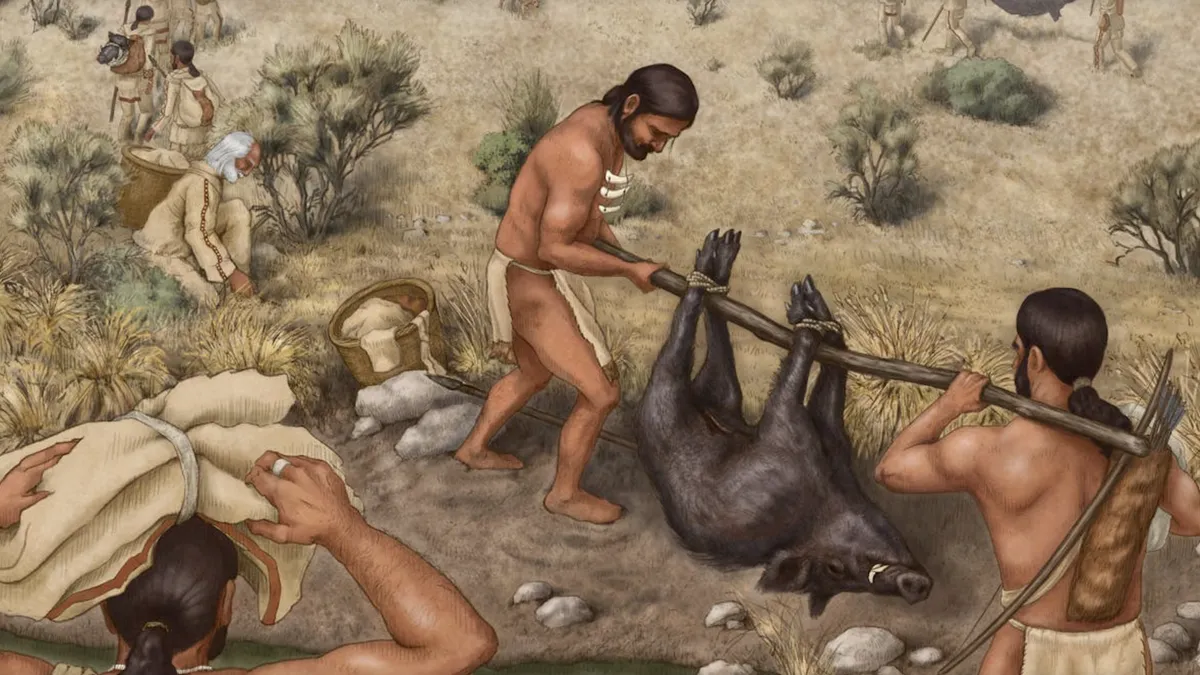

New research suggests prehistoric communities in Iran’s Zagros Mountains transported wild boars over 70 kilometers to participate in elaborate communal feasts—long before the dawn of agriculture.

In a remarkable discovery that reshapes our understanding of prehistoric social life, archaeologists have uncovered evidence of large-scale feasting in the Zagros Mountains of western Iran—dating back more than 11,000 years. At a site known as Asiab, researchers found the skulls of 19 wild boars neatly packed into a pit, their butchery marks revealing they were used in a grand communal celebration.

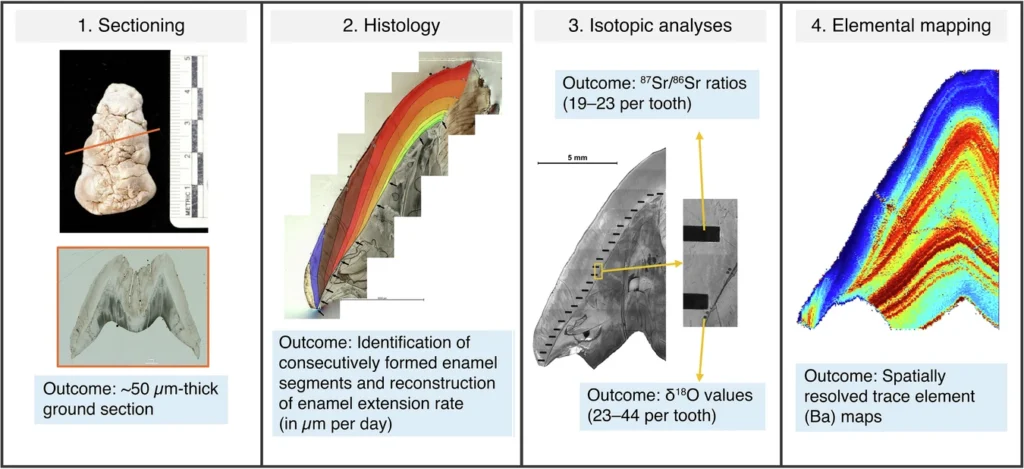

What makes this discovery truly extraordinary, however, is not just the age of the feast—but the lengths to which participants went to contribute. According to a study published in Nature Communications Earth & Environment and summarized in The Conversation by lead author Dr. Petra Vaiglova, isotope analysis of tooth enamel revealed that at least some of the wild boars were transported over mountainous terrain from distances of 70 kilometers or more.

“Just like bringing a bottle of regional wine to a dinner party today, these animals appear to have served as meaningful gifts,” wrote Vaiglova, a researcher in archaeological science.

A Prehistoric Tradition of Sharing and Symbolism

Feasting is commonly associated with agricultural societies, which had the means to produce surplus food. However, the Asiab site challenges this narrative. It demonstrates that pre-agricultural communities were capable of organizing complex social events involving symbolic exchanges and long-distance resource transport.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The findings support the idea that such feasts may have played a key role in shaping early human social bonds—possibly even contributing to the eventual development of farming practices. In a broader cultural sense, the effort to bring animals from distant locations implies a powerful form of gift-giving, echoing modern traditions where regional foods are shared during holidays or celebrations.

“Reciprocity is at the heart of social interactions,” Vaiglova noted. “Just like a thoughtfully chosen bottle of wine does today, those boars brought from far and wide may have served to commemorate a place, an event and social bonds through gift-giving.”

Teeth Tell the Tale

The team used a technique that examines microscopic growth patterns in tooth enamel—much like counting tree rings—to determine the animals’ life histories and movements. Isotopic data indicated varied environmental conditions during tooth development, suggesting the boars originated in different parts of the region before converging at Asiab.

This is the first time such behavior has been documented in a pre-agricultural society in the Near East. Similar findings have been observed at Stonehenge in the UK, where people brought pigs from across Britain to large ceremonial feasts—but those occurred much later, in farming contexts.

Redefining Ancient Community Life

The Asiab feast offers a rare glimpse into how prehistoric humans expressed community identity, maintained social cohesion, and marked significant occasions—all through the medium of food.

Whether it’s crocodile jerky from Australia or French cheese, food still serves as a cultural ambassador today. The ancient boars of Iran prove that this tradition has roots deeper in history than we ever imagined.

Vaiglova, P., Kierdorf, H., Witzel, C. et al. Transport of animals underpinned ritual feasting at the onset of the Neolithic in southwestern Asia. Commun Earth Environ 6, 519 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02501-z

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Cover Image Credit: Artistic reconstruction of early humans transporting a wild boar across rugged terrain to a communal feast in ancient Iran. (Illustration by Kathryn Killackey)