A new study on inscribed clay tablets that were used in the treasury archives of the Achaemenid Empire revealed that the workers of the mighty kingdom were paid for their wages with silver coins.

Iranian experts managed to decode the texts found on clay tablets. They were created during the reign of the Persian king Darius the Great. As could be ascertained, it turned out to be just a kind of “accounting records” which confirm that the workers’ wages at that time were actually paid in silver.

Conducted by Iranian archaeologist Soheli Delshad, the study investigated 33 clay tablets, the majority of which dating back to the time of Darius I (Darius the Great), who was the third Persian King of Kings, reigning from 522 BC until he died in 486 BC.

Darius I (Darius the Great) was one of the greatest rulers of the Achaemenid dynasty, who was noted for his administrative genius and his great building projects.

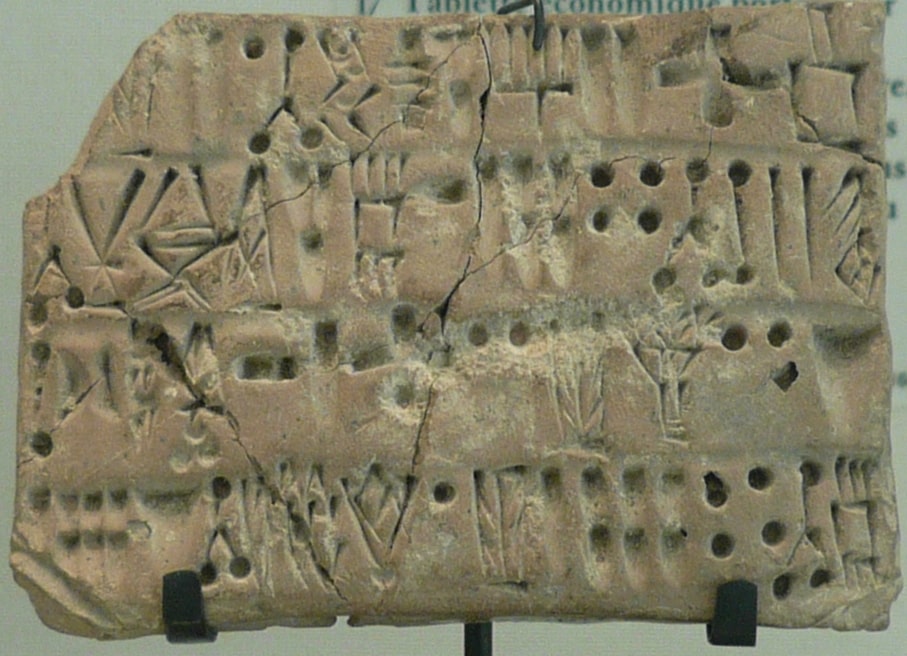

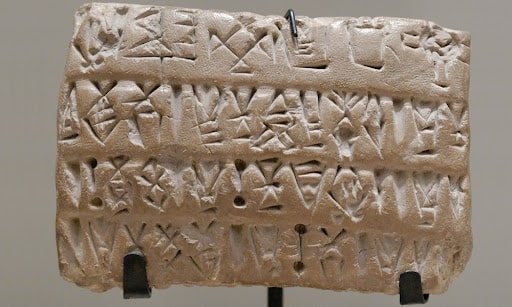

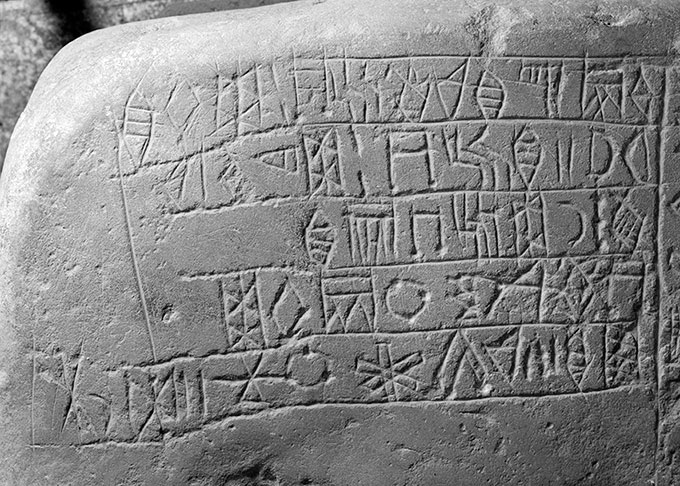

Delshad told ILNA on Wednesday that 28 of the tablets, all of which carry Elamite cuneiform, were chosen from Persepolis’ royal treasury and the remaining four from a fort archive.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The tablets reveal that the wages of workers were paid in silver from the king’s treasury, he stated.

Soheli Delshad and his colleagues worked hard to decipher what was written. The tablets indicated to whom the salary was paid and in what amount. At the same time, only silver coins were taken from the royal treasury. A total of 136 people are said to have worked as plasterers or bricklayers. It is worth mentioning that this is the first time that it has been able to get genuine proof that workers’ salaries were paid in silver.

Hundreds of Achaemenid clay tablets and related fragments, which had been on loan from Iran to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago since 1935, were returned to Iran in 2019.

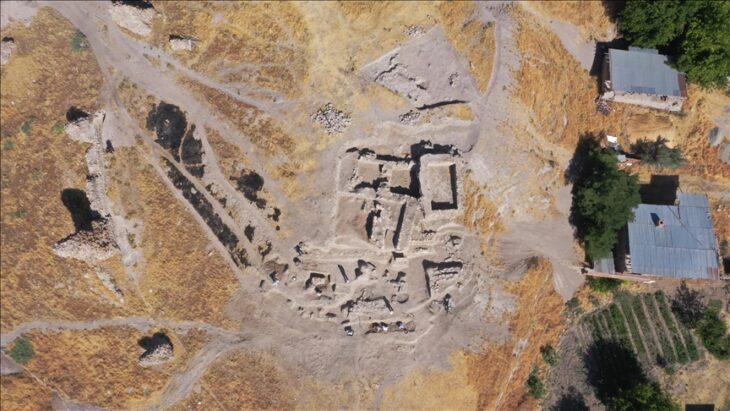

Archaeologists from the University of Chicago found the tablets in the 1930s while digging in Persepolis, the Persian Empire’s ceremonial capital. The Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, however, has resumed work in conjunction with colleagues in Iran, and the repatriation of the tablets is part of an expansion of relations between researchers in the two nations, according to Gil Stein, director of the Oriental Institute.

The tablets reveal the economic, social, and religious history of the Achaemenid Empire (550-330 BC) and the larger Near Eastern region in the fifth century BC.

Elamite language, an extinct language spoken by the Elamites in the ancient nation of Elam, encompassed the territory from the Mesopotamian plain to the Iranian Plateau. According to Britannica, Elamite documents from three historical periods have been found.

The earliest Elamite writings originate from the middle of the third millennium BC and are written in a figurative or pictographic script.

Texts from the second era, which spanned from the 16th to the 8th centuries BC, are written in cuneiform; the linguistic stage seen in these documents is often referred to as Old Elamite.

The last period of Elamite writings is that of the Achaemenian rulers of Persia (6th to 4th century BC), who employed Elamite in their inscriptions alongside Akkadian and Old Persian. This period’s language, which was likewise written in cuneiform script, is known as New Elamite.

Cover Photo: Tablet in Elamite language, from Louvre. Wikipedia