A groundbreaking archaeological discovery in northern Iraq reveals that a mysterious layer of sand beneath an ancient temple may reshape what we know about Mesopotamian religion, architecture, and cultural exchange.

Archaeologists working at the ancient city of Assur, once the spiritual and political heart of the Assyrian world, have uncovered a surprising secret hidden beneath the foundations of the Ishtar Temple. Beneath the stone and brick lies a thick, deliberately placed layer of sand—one that is now transforming scholars’ understanding of early Mesopotamian civilization.

According to a newly published scientific study, this sand is not local debris or a natural deposit. Instead, it was carefully sourced, transported, and laid down nearly 5,000 years ago, long before Assur rose to imperial power. The discovery offers rare insight into ancient building rituals, long-distance connections, and the early origins of the cult of the goddess Ishtar.

A Temple Built on Purposeful Foundations

The Ishtar Temple in Assur is one of the oldest known religious structures at the site. While archaeologists have studied its walls and artifacts for more than a century, the deepest layers beneath the temple remained unexplored—until recently.

Using modern coring techniques, researchers drilled beneath the temple’s inner chamber and encountered an unexpected feature: a thick, clean sand deposit placed directly under the earliest floor. No tools, pottery, or everyday debris were found within it, suggesting it was not accidental or domestic in nature.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

This matters because in ancient southern Mesopotamia, laying purified sand beneath temples was a known ritual practice. The sand symbolized cleanliness and divine preparation, transforming the ground into a suitable dwelling place for a god. Until now, there was no firm evidence that this tradition extended to northern Mesopotamia—making the Assur discovery a first of its kind.

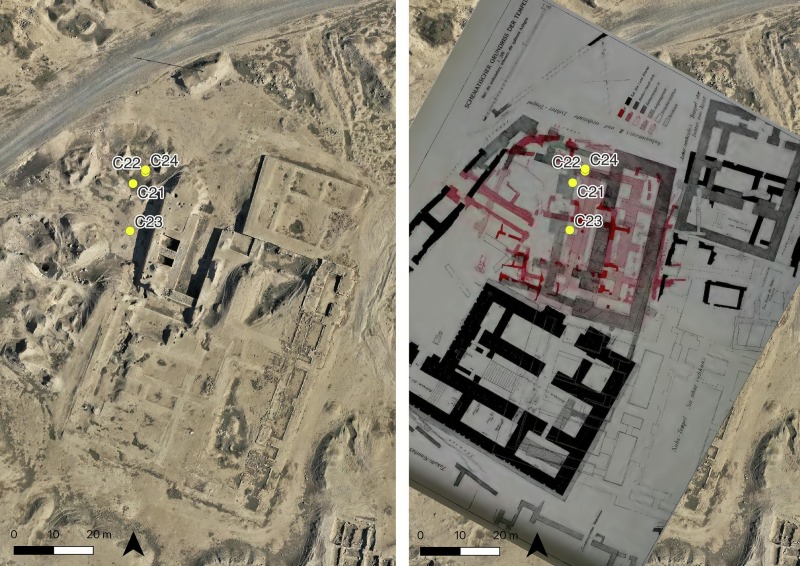

Locations of cores C21–C24 within the Ishtar Temple. The plan on the right (georeferenced from Andrae 1922: pl. 4) highlights the earliest temple phase (Temple H) in red. Adapted from Altaweel (2025: fig. B2.5). Credit: Altaweel et al. (2026)

Where Did the Sand Come From?

The real surprise came when scientists analyzed the sand itself.

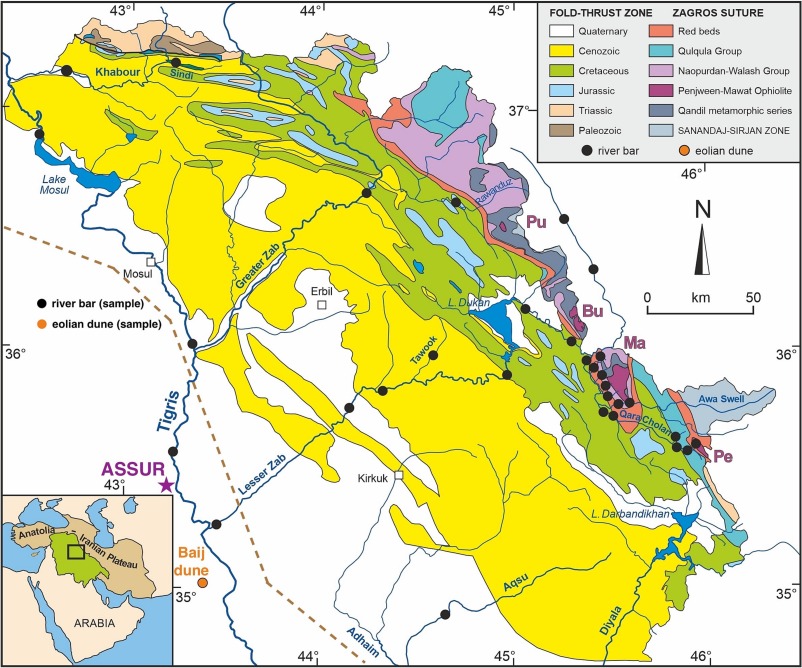

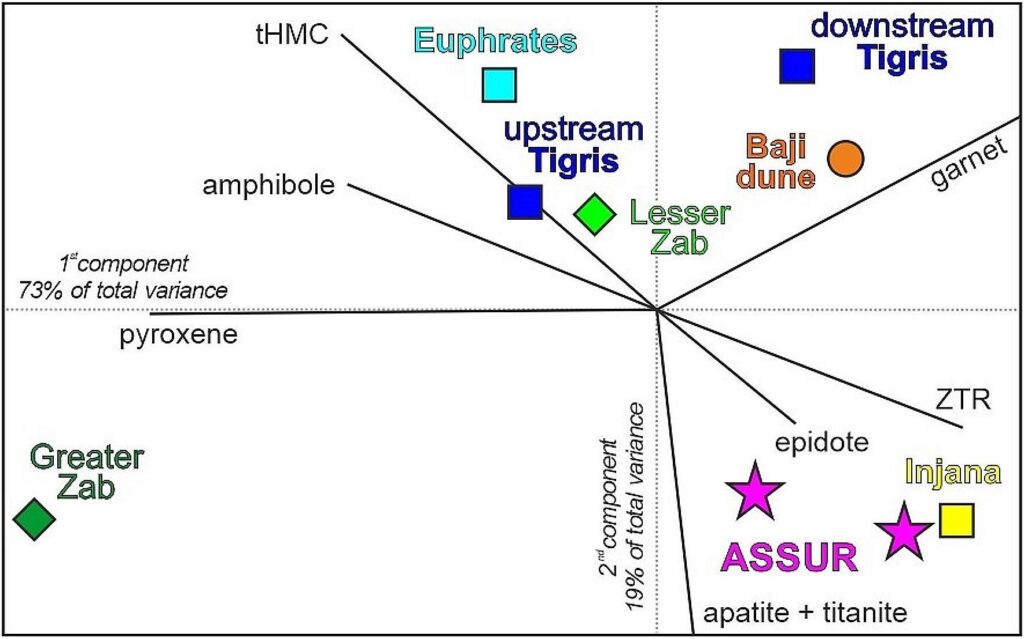

Through detailed mineralogical testing, the research team discovered that the sand did not originate from the nearby Tigris River, even though the river flows directly past Assur. Instead, the sand’s unique mineral composition points to an origin in the Zagros Mountains, over 30–50 kilometers away.

The sand contains rare minerals such as glaucophane and lawsonite, which form only under extreme geological conditions. These minerals act like geological fingerprints, allowing researchers to trace the sand’s journey across landscapes and cultures.

In other words, the builders of the Ishtar Temple deliberately avoided the most convenient local materials and instead chose sand with a specific origin and appearance.

Dating the Birth of Assur Earlier Than Expected

Charcoal fragments found just above the sand layer were radiocarbon dated to 2896–2702 BCE, pushing the foundation of the temple—and possibly the earliest settlement at Assur—back earlier than many scholars had believed.

This challenges long-standing chronologies that placed Assur’s beginnings later in the third millennium BCE. Instead, the city now appears to have been an important religious center much earlier, during a formative period in Mesopotamian history.

Ishtar, Inanna, or a Mountain Goddess?

Beyond architecture and dating, the sand raises deeper cultural questions.

Ishtar is best known from southern Mesopotamia, where she was worshipped as Inanna, a powerful goddess of love, war, and fertility. However, in northern Mesopotamia and the surrounding highlands, a closely related goddess named Shaushka was revered by Hurrian-speaking populations.

The Zagros Mountains—identified as the sand’s ultimate source—were closely linked to Hurrian cultures. This has led researchers to propose a fascinating possibility: the sand may symbolically connect the Ishtar of Assur not only to southern Mesopotamian traditions, but also to mountain-based religious identities.

Rather than choosing one origin, Assur’s early inhabitants may have intentionally blended multiple traditions, reflecting the city’s role as a cultural crossroads.

Why Only This Temple?

Interestingly, similar sand foundations were not found beneath other major temples at Assur, including those dedicated to gods like Sin, Shamash, or Anu. This makes the Ishtar Temple stand out as architecturally and ritually unique.

The selective use of sand suggests that Ishtar held a special status—one that required distinct construction practices and deeper symbolic meaning.

A New Chapter in Mesopotamian Archaeology

This discovery marks the first systematic mineralogical study of temple foundation sands in Iraq, opening the door to new methods and perspectives in archaeology. It shows that even materials as humble as sand can carry powerful stories about belief, identity, and human choice.

By combining archaeology, geology, and history, researchers are now uncovering hidden layers of meaning beneath ancient monuments—quite literally.

Sometimes, the most important clues to civilization are found not in towering walls or golden artifacts, but beneath our feet.

Altaweel, M., Squitieri, A., Eckmeier, E., Garzanti, E., & Radner, K. (2026). The sand deposit underneath the Ishtar Temple in Assur, Iraq: Origin and implications for the foundation of the goddess’s cult and sanctuary. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 69, 105574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2026.105574

Cover Image Credit: The Ishtar Temple of Assur was first exposed by Walter Andrae. Altaweel et al. (2026)