A Mysterious “Buddha Bucket” Survived 1,000 Years in a Viking Grave — and despite spending a millennium beneath layers of soil, wood, and stone, it remains astonishingly intact.

A thousand-year-old wooden bucket discovered in Norway’s famous Oseberg Viking ship burial is drawing renewed global attention, not only for its remarkable state of preservation but also for the mysterious bronze figure attached to it — a Celtic-style motif that looks strikingly like a Buddha. Far from being a Buddhist relic, however, archaeologists say the object tells a powerful story about the cultural exchange, trade, and symbolism that defined the Viking Age.

The bucket, crafted from durable yew wood and reinforced with bronze fittings, was one of the few objects inside the Oseberg burial mound that survived almost intact when the ship was unearthed in 1904. While much of the vessel and its grave goods had been crushed by centuries of soil and stone, the bucket emerged as a rare exception — slightly misshapen, but otherwise astonishingly well preserved.

According to archaeologist Hanne Lovise Aannestad of the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo, the craftsmanship and materials immediately stood out. The detailed bronze figure seated in a cross-legged pose resembles Buddhist iconography at first glance, leading early excavators to nickname it the “Buddha bucket.” Yet researchers now know the figure has no connection to Asia or Buddhism. Instead, its style and metalworking techniques point toward Celtic monastic workshops in what is now Ireland and the British Isles.

A Viking Treasure With a Much Older Past

The bucket itself appears to predate the burial by at least a century, suggesting it was already a prized object before it was laid to rest alongside two high-status women in the Oseberg ship. Archaeologists believe that monks in early medieval monasteries produced objects like this, decorated with intricate geometric patterns and symbolic figures.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

How such an object made its way to Norway remains an open question. Vikings traveled extensively through the British Isles — sometimes as raiders, sometimes as traders, and sometimes as political allies. Elite families exchanged gifts, fostered children across borders, and participated in thriving networks of commerce and diplomacy. The bucket may have been seized during a raid, brought home as a valuable trophy, or even given as a diplomatic gift.

Unlike many imported objects that were dismantled for their metal fittings and reused as jewelry, this bucket was brought back intact. That choice alone suggests it was considered special — perhaps aesthetically impressive, politically meaningful, or spiritually symbolic.

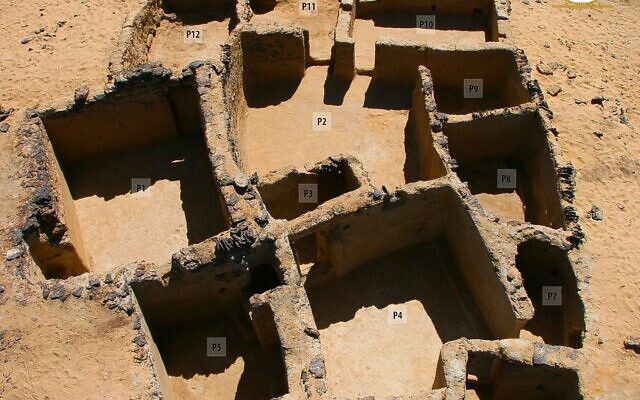

The Oseberg ship, found on a Tønsberg farm, was restored from 2,000 pieces. Its central burial chamber held two women, treasures, textiles, and the Buddha bucket. Credit: Museum of Cultural History / University of Oslo

From Sacred Ritual Motif to Viking Grave Good

The seated male figure on the bronze band has long puzzled scholars. One theory links it to ancient Celtic ritual imagery described in Roman sources, in which sacrificial figures were depicted in cross-legged poses. By the time the bucket was made in the 8th century, such rituals were no longer practiced, but the symbolic imagery may have survived in decorative art.

Similar figures have been found elsewhere in Scandinavia — including the so-called Myklebust man from western Norway — reinforcing the idea that such motifs circulated widely through trade and contact with the Celtic world. These artefacts illustrate how Viking-era Scandinavia was far more internationally connected than once believed.

An Empty Bucket Made From Toxic Wood

What makes the Oseberg bucket even more unusual is that, unlike the other containers in the grave that were filled with food for the afterlife, this one was empty. The reason may lie in the material itself: yew wood is highly durable but also toxic, especially when in contact with liquids. Researchers note that this property would have made the bucket unsuitable for storing food or water — implying it may have served a symbolic or ceremonial role instead of a practical one.

Botanists studying the object have even suggested that its longevity may be linked to the slow-growing nature of yew, which produces dense, resilient timber capable of lasting through centuries underground.

A Story of Loss, Survival, and New Meaning

The Oseberg grave has not survived unscathed through history. Around the year 953, long after the burial, thieves broke into the chamber, disturbing the contents and stealing many of the most valuable items. Beds and chests were overturned, bones scattered, and irreplaceable artefacts vanished forever. Because of this looting, archaeologists today cannot reconstruct the original arrangement of the grave goods — and whatever once filled the bucket, if anything, may have disappeared at that time.

Even so, the bucket remains one of the most evocative surviving objects from the site, symbolizing both disruption and continuity across time.

An Icon for the New Viking Age Museum

Today, the “Buddha bucket” is set to become a flagship symbol of Norway’s new Viking Age Museum, scheduled to open in 2026. Curators chose the object not only for its striking appearance but also for the story it tells — a story of long-distance connections between Vestfold, Ireland, and England; of craftsmanship that blended cultures; and of how Vikings lived in a world far more complex than the stereotypes of plunder and warfare suggest.

With its haunting bronze face, mysterious history, and extraordinary preservation, the Oseberg bucket stands as a reminder that Viking burials were not just graves — they were archives of identity, belief, and global interaction in the early medieval world.

Cover Image Credit: The bucket was placed in the grave when two influential women were buried in 834. A thousand years later, when the Oseberg ship was excavated, almost everything had collapsed — except the remarkably preserved bucket. Aksel Kjær Vidnes