Researchers from the University of Florence, Harvard University, and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig analyzed the DNA of bodies preserved under the ashes at Pompeii, and the results debunked modern-day assumptions about who the victims were.

One of Mount Vesuvius’ most notable eruptions occurred in 79 AD, burying the Roman city of Pompeii and its people beneath a thick layer of lapilli, or tiny stones and ash.

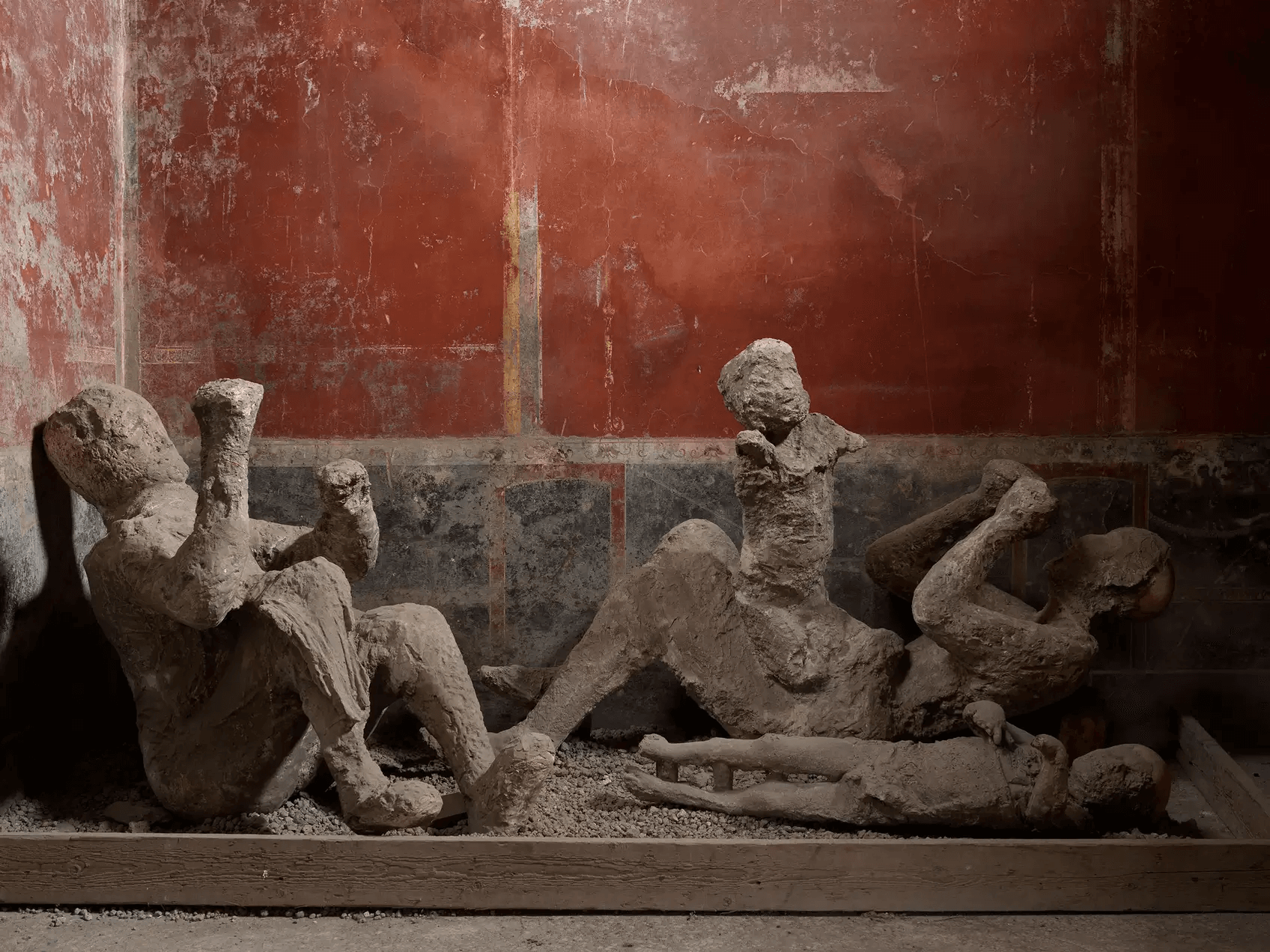

The forms of the victims were preserved as cavities in the ash after their bodies decayed, which archeologists used to create plaster casts. Eighty-six of the casts are undergoing restoration and this provided researchers with the opportunity to examine 14 of them.

The research team extracted DNA from the heavily fragmented skeletal remains embedded in 14 undergoing restoration. This extraction process allowed them to accurately establish genetic relationships, determine sex, and trace ancestry. Interestingly, their findings largely contradicted previous assumptions based solely on physical appearance and the positioning of the casts.

When the bodies were initially found, scientists made conclusions about their relationships based on their location and placement.

David Caramelli of the Universita di Firenze and a co-author of the research said: “This study illustrates how unreliable narratives based on limited evidence can be, often reflecting the worldview of the researchers at the time.”

For example, using DNA extracted from broken bone fragments, the researchers concluded that the adult (long assumed to be the mother) holding a baby and wearing a gold bracelet was actually a man who had nothing to do with the child.

The house that came to be known as “the house of the golden bracelet” contained a number of surprises. More adult remains were believed to belong to the same family nearby. All four, however, were male and unrelated, according to DNA evidence.

Likewise, the researchers were able to show that the stories observers saw in the plaster casts, two women embracing as they died, were not true. Three possible relationships were identified by archaeologists at the time: mother and daughter, two sisters, or lovers. Researchers have now identified the victims as male and female, with one being between the ages of 14 and 19 and the other being 22 after analyzing the skeletal remains.

“We were able to disprove or challenge some of the previous narratives built upon how these individuals were kind of found in relation to each other,” said Alissa Mittnik of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany.

Because the Pompeians came from diverse genomic backgrounds, the genetic data also provided information about their ancestry. The finding that they were mainly descended from recent immigrants from the eastern Mediterranean highlights the cosmopolitan nature of the Roman Empire.

The researchers revealed that the ancient people were descended from ancestors who probably came from central and eastern Türkiye, Sardinia, Lebanon, and Italy, as well as groups from the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa.

Their research was published on Thursday in the journal Current Biology.

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

Cover Image Credit: Group of casts from the House of the Golden Bracelet. Casts no. 50-51-52, date of creation 1974. Photo: Archaeological Park of Pompeii