New research reveals that about 12,000 years ago, in northern Israel, humans turned the bones of small birds into instruments that imitated the songs of certain birds.

The small flutes could have been used to make music, call birds or even communicate over short distances, the researchers suggest on June 9 in Scientific Reports.

The authors of the study explain that Palaeolithic communities could use the sound of these objects to communicate, attract preys when hunting, or even to make music.

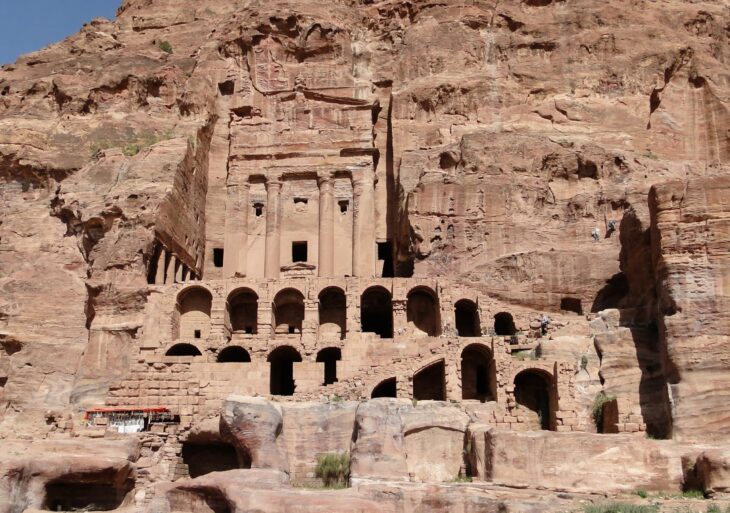

An international team of archaeologists and ethnomusicologists led by José Miguel Tejero, researcher at the University of Barcelona’s Prehistoric Studies and Research Seminar (SERP) and the University of Vienna’s Laboratory of Paleogenetics, and Laurent Davin, from the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), conducted the study. The objects were discovered at the archaeological site of Eynan (Ain Mallaha) in northern Israel, which dates from the Late Natufian archaeological period or culture and has been excavated by a Franco-Israeli team since 1955.

The archaeological site of Eynan (Ain Mallaha)was inhabited from 12,000 BCE to 8,000 BCE, around the time when humans were undergoing a massive revolution from nomadic hunter-gatherers to more sedentary, semi-settled communities.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The French-Israeli team of archaeologists discovered fragments of seven different flutes, dating to around 10,000 BCE, which is the largest collection of prehistoric sound-producing instruments ever found in the Levant.

Dr. Laurent Davin, a postdoctoral fellow at Hebrew University, was looking over some of the recovered bones when he noticed tiny holes drilled at regular intervals along a few of them. The holes were initially dismissed by experts as normal wear and tear on the delicate bird bones. However, when Davin examined the bones more closely, he noticed that the holes were at very even intervals and were clearly made by humans.

“One of the flutes was discovered complete, and so far as is known it is the only one in the world in this state of preservation,” Davin said in a press release that accompanied the article’s publication.

The instruments were unearthed from the remains of small stone dwellings at a lakeside site called Eynan-Mallaha. All of the flutes were made from the wing bones of waterfowl that spent winter months at the lake, Laurent Davin notes. Of the seven flutes found, the largest appears to be intact and is about 63 millimeters (2.5 inches) long.

The wing bone of a modern female mallard was used by Davin and his team to create a precise replica of the prehistoric flute. When played, the instrument made high-pitched sounds similar to common kestrel and Eurasian sparrowhawk calls, raising the possibility that the instruments were used to entice birds.

Davin says that such flutes may have been worn while hunting. The largest flute was red ochre-decorated and had a worn spot where it may have hung from a string or a strip of leather.

The flute represents an important discovery, but it’s not music to everyone’s ears. But it opens a window into a fascinating point in human development, the complexity of society and their ability to make tools.

The tiny finger holes drilled with talons at regular intervals in the 12,000-year-old flute discovered in northern Israel Photo: Hamoudi Khalaily/IAA