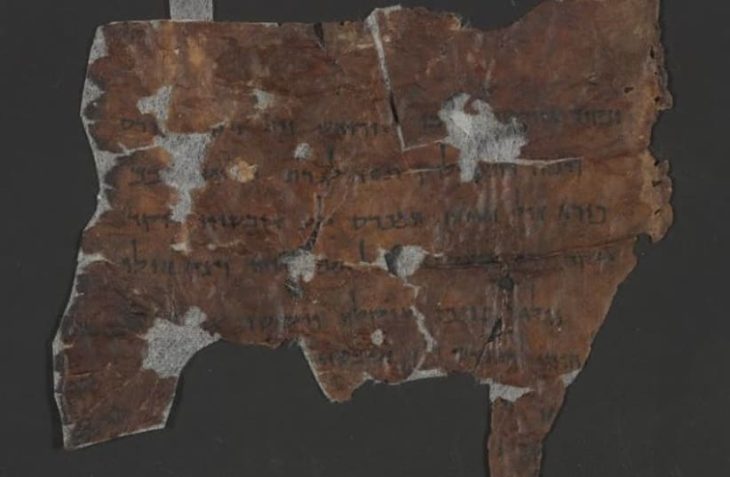

Researchers at the University of Copenhagen have successfully extracted the complete human genome from “chewing gum” thousands of years ago. According to the researchers, it is a new untapped source of ancient DNA.

A 5,700-year-old lump of pitch tar provided archaeologists with intriguing details about the intimate details of a Danish Stone Age woman – and “chewing gum” sheds new light on the evolution of our species.

Paleolithic chewing gum found on an island known for its mud was perfectly preserved, and scientists were able to determine the color of skin, hair and eyes, pathogen profile, dental condition, diet, and more from the DNA inside it.

On the field, scientists were able to collect her entire genome as well as the genomes of other species that inhabited her mouth. She was lactose intolerant, seemed to prefer wild food to basic grain products, and was a carrier of the viral infection that many of us have today.

“It is amazing to have gotten a complete ancient human genome from anything other than bone,’’ says Associate Professor Hannes Schroeder from the Globe Institute, University of Copenhagen, who led the research.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“What is more, we also retrieved DNA from oral microbes and several important human pathogens, which makes this a very valuable source of ancient DNA, especially for time periods where we have no human remains,” he adds.

Sealed in mud

This individual, named “Lola” after the island where the gum was found, had dark skin, suggesting that northern Europeans’ adaptive lighter skin evolved much later. She could chew gum made of birch bark for many reasons.

The earliest known use of birch pitch dates back to the Palaeolithic. As the primary Stone Age adhesive, the resin of various trees becomes more pliable the more it is heated, and chewing may have been a way of keeping it pliable as it becomes cooler when heated. There’s also the possibility that its antiseptic properties prompted her to chew it to ease toothache, or she might just enjoy the monotonous biting that makes many of us chew gum today.

The birch pitch was discovered during an archaeological excavation in Syltholm, east of Rødbyhavn in southern Denmark.

“Syltholm is completely unique. Almost everything is sealed in mud, which means that the preservation of organic remains is absolutely phenomenal,” says Theis Jensen, Postdoc at the Globe Institute, who worked on the study for his PhD and also participated in the excavations at Syltholm.

“It is the biggest Stone Age site in Denmark and the archaeological finds suggest that the people who occupied the site were heavily exploiting wild resources well into the Neolithic, which is the period when farming and domesticated animals were first introduced into southern Scandinavia,” he adds.

Lola lived at a time when hunter-gatherers and farmers lived in the same areas – something that wasn’t always considered likely. Her penchant for mallard duck and hazelnut while other Paleo-Danes ate their crops further strengthens this theory, as does her inability to tolerate lactose, commonly seen in northern Europeans after animal domestication.

The study was supported by the Villum Foundation and the EU’s Horizon 2020 research program through the Marie Curie Actions.

Cover Photo: Artistic reconstruction of the woman who chewed the birch pitch. She has been named Lola. Illustration by Tom Björklund.